Evaluating the Oscars

A.O. Scott makes his picks, explains Hollywood’s trends, and suggests what they’re missing

Second of two parts.

Hollywood’s elite will assemble Sunday for the 87th annual Academy Awards. In an interview with the Gazette, New York Times film critic A.O. Scott ’87-’88 explained that Oscar winners often represent “the story the Academy wants to tell about itself.” Based on the movie he thinks will win best-picture honors, Scott said the film industry’s 2014 narrative embraces the notion that “there is still great possibility and novelty left in movies.”

Scott also revealed some of his Oscar picks, the movie he enjoyed most in 2014, and his thoughts on the road ahead for women in film.

GAZETTE: I am curious about the nuts and bolts of your work. How many films a week do you see? How do you decide who sees what? Do you watch them at home or in a theater?

SCOTT: My colleague Manohla Dargis and I split the title of chief critic, so we basically take turns picking first. We also try to take turns if there’s a major director or star. So if I did the last Wes Anderson movie, she’ll have the first chance to do the next one, that kind of thing. So we pick what we are interested in writing about, which is usually two or three movies a week, depending on the week. We probably each review about 150 movies a year. So we will take ours, and the rest will be assigned. Stephen Holden is the other staff critic at the paper. Then we have some freelancers who do the rest, so we cover as close to all of the releases as we can manage with the space and the budget.

I almost never review a movie unless I’ve seen it on a screen. There are a few exceptions to that, if it’s a tiny release, and they can’t afford to rent out a screening room to show the print or the DCT (videocassette), they’ll send me a disc. But virtually all the movies I see are either in festivals or at press screenings in New York.

GAZETTE: Do you ever see them in a crowded theater?

SCOTT: We have to see them before they open. But a lot of them, especially the bigger commercial movies, schedule sneak previews, which are in big multiplex theaters that have, in addition to critics and press, people who have gotten passes or whatever. Comedies and action movies tend to be seen that way, which is useful, because you can sort of get a sense of the reaction of the audience.

GAZETTE: Does a crowd’s reaction ever have an effect on how you review a film?

SCOTT: Oh, yeah, definitely. It certainly does. If, for example, you are at a comedy and nobody’s laughing (you might be laughing), but it’s interesting if you are at a comedy aimed at teenagers and the teenagers are bored and throwing popcorn. That can tell you something. Or, I remember going to one of the “Twilight” movies, in a crowded theater that was packed with 12- and 13-year-old girls and their mothers. I don’t think you can understand that movie unless you’ve seen it in that audience because there are certain cues, like when Taylor Lautner [who plays Jacob Black] takes off his shirt. I think it was in the second one. They are riding the motorcycle, and Bella Swan [played by Kristen Stewart] falls down and hurts her head, and he rips off his shirt to blot the wound, and everyone just went crazy. So that’s a moment of cinema that you haven’t seen unless you’ve gotten that reaction to it.

A.O. Scott on the Oscars

GAZETTE: Is there a film that you can go back to over and over again, one that continues to haunt you, or you never tire of?

SCOTT: There are a few. The test is if you stumble across it on cable and you just keep watching it. It sometimes surprises me what those movies are. They are not always movies where I would say, “That’s my favorite of all time.” But certainly “The Godfather” movies are like that for me. “Pulp Fiction” is like that. “Pulp Fiction” is not a movie I am sure I entirely liked, but it is impossible to stop watching that movie if you enter it at any point. It’s such a sticky and seductive movie.

And I think there are some directors who can do that. I think just about any Orson Welles movie has that effect — “Citizen Kane,” certainly. Recently, I was giving a talk, and I was just looking for a clip, just one little scene in this movie “The Stranger” that he did in 1946, where he plays this ex-Nazi who is hiding in this small town, and I ended up watching the whole movie. I’ve seen it a bunch of times. It’s a flawed movie. It’s not “Touch of Evil” or “Third Man” or “Citizen Kane.” But there is something that he does both as an actor and as a director that you just can’t stop, you can’t let go of. I feel that way about a lot of Mel Brooks movies, too. I can’t get enough of them.

GAZETTE: Do you have a favorite director?

SCOTT: I have a pantheon: Billy Wilder, Preston Sturges, Luchino Visconti, Vittorio De Sica, François Truffaut, Akira Kurosawa, Clint Eastwood, Luis Buñuel, for starters.

GAZETTE: Turning to this year’s Oscars, which movie will take home the award for best film, and why?

SCOTT: I think “Boyhood” will win best film. I think there’s a little bit of a groundswell for “American Sniper,” which has done astonishingly well at the box office. But I think it’s probably a little too hot a button for best picture. I think that the way that “American Sniper” would be represented is Bradley Cooper takes the best-actor award. But I think that “Boyhood” is such a wonderful story, not just the story within the movie, but the story of the movie is such a crazy idea against the odds. Take 12 years to make a movie. And it was a big art-house breakout. People really embraced it and loved it. I think there is a lot of good will toward it.

I think the thing about the Oscars is that it’s always about the story that the academy wants to tell partly about itself. What does the American film industry want to say about itself? And there are different stories that it likes to tell. Sometimes the story is that we are going to embrace something that was very popular, which might be “Gladiator” or might be “Argo.” Sometimes it’s, “We’re going to embrace something that is important and topical and socially relevant,” like “12 Years a Slave” or “The Hurt Locker.” And I think that this may be the compelling narrative this time, the thing that looks fresh and that tells a story about there still being great possibility and novelty left in movies. I think “Boyhood” kind of tells that story. It’s a very accessible and emotionally satisfying story, but it’s also something new. It’s an experiment.

This is kind of mind-reading on the academy, and I may be totally wrong, but I do think there’s a sense that the movies have lost ground to television artistically and in terms of novelty and cultural cachet. And a movie that can counter that, which I think in a way “Boyhood” does, is important. It’s youthful, it’s open-ended, it’s real-time. “Boyhood” was an independent release and director Richard Linklater is a bit of an outsider in Hollywood, which in most years would push against it. IFC, which financed and released the film, has never been much of an Oscar player. But “the little movie that made the big splash” is a good story for them to tell.

‘Movies have been on the verge of extinction for almost as long as they have existed.’

GAZETTE: What do you think of the re-emergence of TV? Does that threaten the vitality of the movie industry?

SCOTT: Well, it’s slightly complicated because it’s not entirely separate from the movie industry. HBO is a Time Warner company, and Sony produces a lot of television as well as a lot of movies, and NBC and Universal, these are parts of the same corporate entities. IFC started as a cable channel, and it’s the distribution arm of that channel, and it also owns a theater in New York. What’s happening is there has been a great artistic flowering. In a way, television in the last 10 or 15 years began to realize some of the aesthetic potential that it hadn’t been able to before. And that was partly because of the business model of premium cable and subscription so that, with shows like “The Sopranos,” it was possible for TV to take a chance on those.

Right now there is enormous growth, something of a bubble, because there is just more and more and more. And you have Hulu and Amazon and Netflix producing original content, in addition to the networks and cable. So it’s very crowded. And you have movies entering those platforms through video on demand and streaming technologies.

We are at this moment — and we think about it a lot as critics, and even at the paper in terms of who gets assigned what — figuring out what counts as TV and what counts as movies. The boundaries are really sort of blurring. I think that people still like going to the movies, and people also have all of these other ways to look at moving images. And there’s a lot of creative cross-migration. You have people going back and forth between movies and TV from project to project. So you have someone like Lena Dunham, who is a filmmaker but does a TV show, or the Duplass brothers, who made a bunch of films and now they are doing a show for HBO. Steven Soderbergh, David Fincher, lots of people are moving back and forth. So I think we’re kind of reaching a point — we’re not at it yet, and it will take a while for it all to shake out — where what we assume to be clear boundaries between a movie and a TV show, or for that matter a TV show and a Web series, get much fuzzier. So we are going to have to rethink how we sort out all the different kinds of moving-picture narrative entertainment that comes our way.

GAZETTE: Do you still think there is an appetite for movies?

SCOTT: Movies have been on the verge of extinction for almost as long as they have existed. First there was the Paramount consent decree in 1948, the antitrust decision that movie studios had to divest from all of their theater chains so they couldn’t control exhibition. And then in the 1950s, with the rise of television, that was going to be the end, and there was a huge, huge drop-off in attendance. And in the ’80s again, it was the VCR. Then it was the Internet, or the new “golden age” of television. On the one hand, none of those things have killed movies or moviegoing, and I don’t think any of the new stuff will either. But all of those things have changed the business and have transformed it, both technologically and sociologically. So it may be that certain kinds of stories and certain kinds of visual approaches make more sense on the big screen, and some on the small.

GAZETTE: You mentioned “American Sniper.” What do you think about the controversy around the film?

SCOTT: I reviewed it in the paper when it opened in New York early. That review was on Christmas, and it was sort of before things hit the fan. I have mixed feelings about the movie. I am a great admirer of Clint Eastwood as a director and I think it’s the strongest directing that he has done in a while, maybe since “Million Dollar Baby” or “Gran Torino,” and it’s a Clint movie. You know, it has a kind of bluntness and very sort of effective, emphatic storytelling style, kind of cleanly and classically shot and edited, and it is entirely from within the perspective of its main character.

There are things that are very troubling about it, just as an account of recent history. The way it slides from 9/11 to the Iraq War and the way it presents that war as a very stark and clear battle of good and evil, I kind of tend to think of that less as a political statement than as a kind of genre convention. The movie is a Western as much as it’s a war movie. He’s a lone, solitary gunman.

And there’s a very consistent theme throughout Eastwood’s career, which is the idea that there’s evil in the world, and violence is a necessary response to that evil, and it’s also one that has terrible consequences, including on the people whose job it is to carry it out. That’s the theme of “Unforgiven,” that’s the theme of “Mystic River,” that goes all the way back to “Dirty Harry,” which “American Sniper” resembles a lot. And certainly there are political implications of that worldview, but it’s Clint Eastwood.

I find judging it by how much it may or may not conform to my own political views to not be a very interesting way to think about movies. So I suspect that Eastwood and I, if we sat down talking about politics, we might disagree about a lot of things. But so what? At the same time, the history is recent enough, and the politics is live enough that the movie did trouble me a little bit. But I don’t think it’s as simple as either its harshest detractors or its champions say it is. It’s a movie that has some shadows, and some ambiguity. I don’t think it’s necessarily an antiwar movie, but I also don’t think it’s a jingoistic, militaristic movie.

I think it’s haunted. There’s stuff around the edges. On the one hand, it takes Chris Kyle entirely at his word. Of course, as we know, his word wasn’t always reliable. In terms of what he’s doing and what he believes, it takes him at his word and presents him as who he says he is. But there are all sorts of stuff around the edges. He responds to encounters with fellow soldiers who are having their doubts, who are kind of turning against the war, including an encounter with his own brother. And those moments kind of do cast a shadow, and they can make you wonder about the guy. OK, how come he isn’t asking any questions? Why is he so committed to keeping it simple, in a way? So I think it’s a complicated movie. And I don’t think that it’s a movie that sits comfortably on either side of the debate that’s been going on around it.

A sampling of Oscars with a Harvard touch

2.043009_ArtsMedal_KS_148.jpg

John Lithgow ’67 fell in with the theater crowd while at Harvard, took a role in a campus production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “Utopia Limited,” and never looked back. His successful career in theater, TV, and film includes many acting accolades, among them Oscar nominations for best supporting actor in 1982 for “The World According to Garp,” and in 1983 for “Terms of Endearment.” File photo by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

3.120301_Guggenheim_Davis_2.JPG

Elisabeth Shue took time off from Harvard in the 1980s to pursue her acting career. The move paid off. In 1995 she received an Academy Award nomination for best actress for her turn as a prostitute in the drama “Leaving Las Vegas.” Shue eventually returned to campus and earned her College degree in 2000. File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

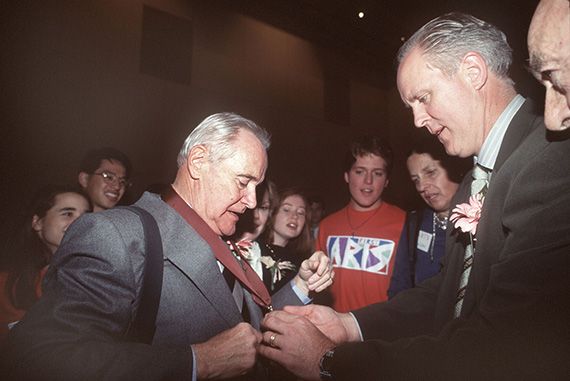

4.Harvard Arts Medalist, actor, Tommy Lee Jones visited the 20th Arts First Festival and was videotaped in Massachusetts Hall at Harvard University.

Tommy Lee Jones ’69 caught the acting bug in second grade playing Sneezy in “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” Years later, he honed his skills in a number of Harvard undergraduate productions such as Christopher Fry’s “The Lady’s Not for Burning,” opposite his friend and fellow student John Lithgow. Jones has received three Academy Award nominations, winning one as best supporting actor for his portrayal of federal marshal Samuel Gerard in the 1993 thriller “The Fugitive.” File photo by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

5.Bravo_Lithgow_John_15.jpg

The Harvard Glee Club and Harvard’s Hasty Pudding Theatricals helped jumpstart Jack Lemmon’s legendary career. A Hollywood icon, Lemmon ’47 earned eight Academy Award acting nominations, including two wins: one for best supporting actor in the 1955 film “Mister Roberts,” and one for best actor in the 1973 film “Save the Tiger.” File photo by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

GAZETTE: Do you feel like there was one film that was unfairly ignored by the Oscars this year?

SCOTT: I really loved “Selma.” I am glad it got the best-picture nomination. I think that David Oyelowo as King definitely deserved a nomination. I think also that its director, Ava DuVernay, deserved one because I think that it’s a very well-directed movie, and it’s a very complicated story told with a lot of clarity and nuance. Otherwise, my tastes and the Oscar tastes tend not to converge all that often. I never feel particularly disappointed or excited one way or the other because often the movies that I am most excited about are not nominated. I thought this movie “Beyond the Lights” was really terrific, but it got nothing. “Wild” was a movie that, though it got two acting nominations for Reese Witherspoon and Laura Dern, the fact that it got no writing or directing or other nominations, I think, is an index of the sexism of the academy. If you look at all of the nominees in all of the major, non-acting categories, without exception, they are stories about men, every single one. “Boyhood,” “Birdman,” even “Selma,” “American Sniper.” All down the line, “Imitation Game,” “Foxcatcher,” “The Theory of Everything.”

So it’s not just, as my colleague Manohla Dargis has brilliantly demonstrated in a series of articles she has been writing, that women filmmakers are ignored and marginalized and discriminated against in Hollywood, but actually women’s stories are undervalued and ignored and overlooked. Somehow “Wild” can be acknowledged because of what Reese Witherspoon and Laura Dern did, but the story itself is kind of judged not to be significant and important enough. It’s actually a very well-directed movie. It’s a very narratively daring movie. It takes a lot of interesting chances. In a way, that kind of result maybe isn’t surprising, but I think it’s disappointing. And again, it’s a sign. It’s something that the movie industry is going to have to deal with. If you look at television, especially at this moment, there are a lot of women’s stories and there are a lot of powerful creators who are women. It just makes the film side of it look really kind of backward and clueless, and I think that is something that can have consequences with audiences.

GAZETTE: Do you see women in film making significant inroads in Hollywood in the next five or 10 years?

SCOTT: It’s hard to say. I was reading an article recently on the Vulture website about how Sundance is a very diverse festival, more and more so, but the movies and the filmmakers who get picked up out of Sundance, who get elevated to the next level in Hollywood, are almost without exception white men. So the Hollywood studios and the agents and the producers with money, they go talent-scouting and they just find the same kind of people all the time. I’m hopeful. I think that attention is being brought to this, through Manohla’s articles and through public statements by filmmakers, and I think there are filmmakers like Ava DuVernay and certainly Kathryn Bigelow and Nicole Holofcener and Lynn Shelton, and there is something of a movement or a groundswell. But it’s going to take a lot of pushing. It’s frustrating because if you look at where things are commercially, the audiences are ahead of the industry. What were the biggest movies last year? “The Hunger Games” and “Frozen,” “Maleficent.” “The Fault in Our Stars” was a big hit, so clearly there’s an audience and an appetite for stories about women. But that lesson hasn’t filtered into the offices where the decisions are made.

GAZETTE: Was there a film in 2014 that you simply enjoyed the most?

SCOTT: I would say it would be “We Are the Best!,” the Swedish movie about these punk rockers. It is the most purely delightful movie I saw last year. It’s about these three 12-year-old girls who start a punk band, and don’t know how to play any instruments. It’s just great.

GAZETTE: Final question. Any movie star you ever wanted to be, or movie you wanted to be in?

SCOTT: Marcello Mastroianni in “La Dolce Vita.” [Laughs] Yeah. Him, in that movie.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.