“I’ve had a good deal of experience of writing history from the top down. But now, I’m trying to write history from the bottom up, with almost no personal documentation, so I had to figure out other ways of trying to bring people to life,” said Richard Dunn ’50 of the difficulties he faced when writing “A Tale of Two Plantations: Slave Life and Labor in Jamaica and Virginia.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Slavery’s lost lives, found

Historian Richard Dunn’s 40-year study of plantations in Jamaica and Virginia

In the early 1970s, historian Richard Dunn ’50 tasked himself with a nearly impenetrable intellectual inquiry: to compare the conditions, trends, and quality of life in slave communities in the United States and the Caribbean during the 18th and 19th centuries.

During the next 40 years, Dunn, the Roy F. and Jeanette P. Nichols Professor Emeritus of American History at the University of Pennsylvania, meticulously researched the broad arcs and reconstructed the fine details of the operations and lives of more than 2,000 slaves at Mesopotamia, a sugar estate on Jamaica’s western coast, and at Mount Airy, a tobacco and grain plantation in tidewater Virginia. The result is a richly drawn portrait that offers scholars a rare longitudinal view of bondage and its effect on families, as seen through the family trees of two enslaved women, Sarah Affir of Mesopotamia and Winney Grimshaw of Mount Airy.

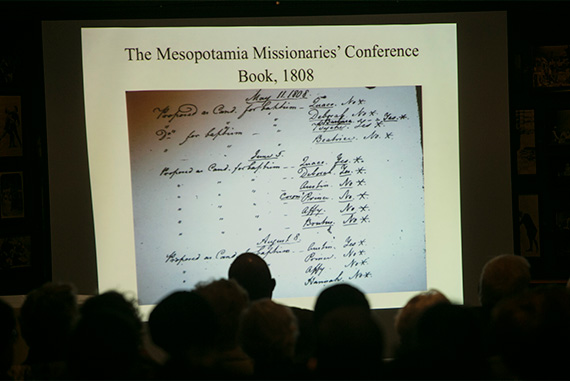

Sifting through an unusually large cache of missionary diaries and records, including slave inventories kept by Mesopotamia owners, the Barham family, and the Tayloe family, who owned Mount Airy, Dunn was able to document the final three generations of slaves at the two plantations before slavery ended in both places.

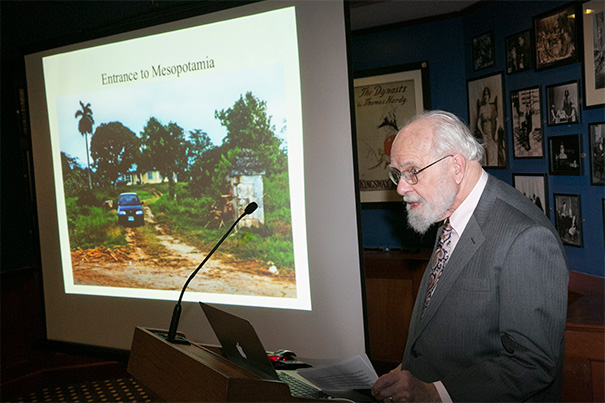

“I’ve had a good deal of experience of writing history from the top down. But now, I’m trying to write history from the bottom up, with almost no personal documentation, so I had to figure out other ways of trying to bring people to life,” said Dunn of the difficulties he faced.

Dunn spoke Feb. 5 during a talk at the Harvard Faculty Club about his book “A Tale of Two Plantations: Slave Life and Labor in Jamaica and Virginia,” recently published by Harvard University Press. He was introduced by Harvard President Drew Faust, a Civil War historian who studied with Dunn as a graduate student at Penn in the early 1970s.

Dunn’s early strategy was to find two sets of plantation workers who would represent population loss-and-gain trends, settling on Mesopotamia and Mount Airy because they maintained extensive records, keeping lengthy slave inventories over the years that documented the names, ages, genders, health, and occupations of workers from year to year. “Cobbled together, you get the outline of a life,” he said.

Overall, the paperwork helped Dunn track 1,103 slaves at Mesopotamia between 1762 and 1833, the year before slavery ended in Jamaica, and 973 slaves at Mount Airy between 1789 and 1863.

His work grew more complex as he got deeper into the research, but he held fast to two “tightly intertwined” goals. “First, [the research] compares slave life on two plantations … and I do this comparison in order to demonstrate the huge differences between the British Caribbean and the U.S. slave systems,” said Dunn. “My second goal is to demonstrate the impact of demography — drastic population loss in the Caribbean; vigorous population growth in North America — among the enslaved black people who lived in those two regions.”

The brutal physical labor required of Mesopotamia’s sugar cane fields led to high death rates among men, while malnourishment and disease contributed to consistently low birthrates for women, unlike the population explosion that went on at the Mount Airy plantation.

“The Mesopotamia slaves were victimized by continuous disease and death, while the Mount Airy slave families were routinely ripped apart” and sold off at great profit, or shipped out of state to serve the Tayloe family’s growing cotton interests in Alabama, a capricious practice and a “shocking abuse,” Dunn said.

“What we have here is ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ writ large — that is, the same kind of damage that made that romantic novel so gripping,” said Dunn. “And I feel that that kind of manipulation is really just about as bad as working them to death, which is what happened in Mesopotamia.”

Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, noted that Dunn’s work, in addition to providing important scholarly insights, offers vital new genealogical information to the many African-American descendants of these particular slave populations. Typically, African-Americans are not able to trace their family histories much earlier than the 1870 U.S. Census because of a lack of record keeping during slavery, said Gates, who also hosts the PBS television program “Finding Your Roots.”

While comparative, Dunn said the book doesn’t proclaim one plantation system as less cruel than the other.