Before her lecture on the Grimké sisters, historian Louise W. Knight (left) talks about the new petitions database with Daniel Carpenter, Harvard’s Allie S. Freed Professor of Government.

Photo (1) by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer; (2) Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute/Harvard University

The rule-breaking Sisters Grimke

How 19th-century women got political

A lecture at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study this week included a speech that drew wild applause. That wouldn’t have been remarkable, except that the speech was more than 175 years old.

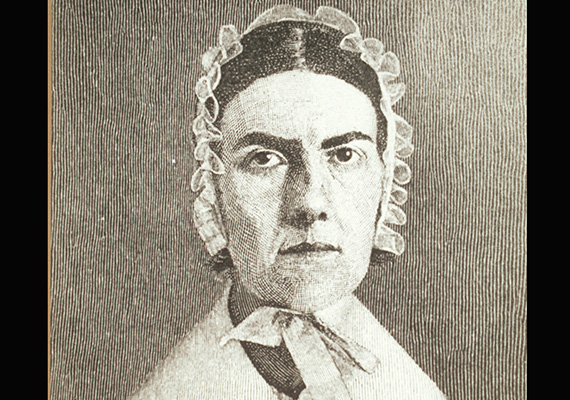

Dramatized in a 2013 video, the speech was delivered to the Massachusetts Legislature in 1838 by anti-slavery advocate Angelina Grimké. It was the first time in U.S. history that a woman had addressed a legislative body. Only a fragment of the three-day oration — its dramatic opening passage — survives.

In those days, the Grimké sisters — Angelina and Sarah — were famous for breaking rules. As anti-slavery advocates canvassing for the cause, they addressed large mixed-gender audiences in public venues, a reversal of custom. And in prescient essays and speeches they delivered a message that combined distress at slavery (widespread and legal) with distress over the status of American women (homebound and unable to vote).

Angelina asked in her 1838 speech, to which 3,000 listeners showed up the first day: “Are we aliens because we are women? … Have women no country?”

As for slavery, the sisters knew it close up. They were part of a wealthy, slave-holding family in South Carolina, but in their 20s they made a cultural escape North to embrace Quaker pacifism in Philadelphia. By 1835, they were writing essays and, later, making speeches on behalf of abolitionist causes that helped create the Civil War.

In 1838, Angelina Grimké was at the State House in Boston to deliver anti-slavery petitions signed by 20,000 Massachusetts women. She told her audience that she had been “exiled from the land of my birth by the sound of the lash, and the piteous cry of the slave.”

The Grimké sisters are little known now. Their story was revived among scholars only in the 1960s. But they represent a breakthrough 19th-century moment in which American women became political. “The 1837 to 1839 period was the peak,” said historian Louise Knight in her Feb. 24 lecture. (She is writing a biography of the sisters.)

Shut out of the voting arena, women in that era turned increasingly to the art of the petition. Often called “prayers,” these were earnest arguments against slavery (or the death penalty, or alcohol), most often appended by collected signatures. In turn, these documents — a traditional way of prompting new laws — were sent to Congress or state legislatures.

A recent study, co-authored by Harvard’s Allie S. Freed Professor of Government Daniel Carpenter, backed up the notion that antebellum petitioning comprised a landmark moment in which women learned lessons of political organization later applied to the suffragette movement.

The study also underscored what is now a historian’s commonplace: that women were far better at petitioning and at gathering signatures than their male counterparts. (“Forget fatigue,” one pamphlet urged women canvassers.) During one 1836 anti-slavery campaign in Massachusetts, women’s groups sent 3,100 petitions to Congress, twice the number sent by men.

That fervor in 1836 was inspired, in part, by a gag rule on anti-slavery petitions passed by the 25th Congress the year before under pressure from pro-slavery Southern Democrats. During this time, former President John Quincy Adams, then a congressman representing the Quincy-Braintree district of Massachusetts, would rise from his seat to offer an anti-slavery petition, only to be shouted down.

The gag rule, Pinckney Resolution 3, was repealed in 1844. But in its day, the rule led — ironically — to an upsurge in such petitions to Congress; inspired more such pleas going to state legislatures; and — above all, said Carpenter — lit a fire under women incensed that their freedom of speech was being even further curtailed.

Among those incensed, and empowered, by the gag rule were the Grimké sisters. This week, by way of Knight’s lecture at Fay House, they became agents of change again, after a fashion. Their skill as petitioners — and that of hundreds of other men and women — is now memorialized in a new database being launched at Harvard Friday at Tsai Auditorium.

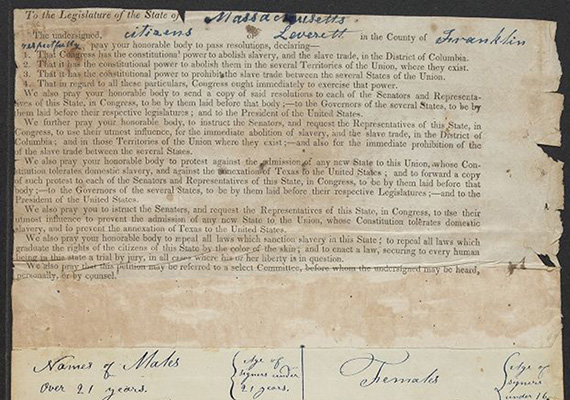

The Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions is the first of its kind, said Carpenter, who is the project’s principal investigator. It represents a largely untapped source of insight and information for scholars: thousands of voices and ideas that were once lost and now — based on the Harvard model — might be found again. In time, he said, similar petition databases can be uncovered, digitized, and made searchable in every state and elsewhere in the world. (Carpenter has a book underway on the multi-local and multi-theme potential of petition archives for scholars, and even for citizens doing genealogical research.)

The Massachusetts iteration launched Friday includes 3,487 digitized petitions from 1649 to 1870, said Nicole Topich, an archivist for the Center for American Political Studies and Carpenter’s collaborator on the new digital archive. There are 11,995 related images in the database, she said; of the 281,996 signatures, at least 81,513 are by women.

Work on the new digital archive, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, began early in 2013 in cooperation with the Massachusetts Archives of the Commonwealth, where Topich set up a small office. The mission: identify, catalog, and then digitize the thousands of anti-slavery and anti-segregation petitions that had lain largely untouched for decades, or even centuries. (Some, said Topich, were covered with soot.)

Some of the documents represent passed legislation. But most of the Massachusetts petitions, still cataloged in a 19th-century index, represent ideas or demands that failed to become law. For one thing, there were so many. For another, most petitions represented ideas that were widely regarded as radical — unthinkable — in their own era.

One 1855 petition, from four men in Tisbury, Mass., petitioned that woman be given the right to vote and hold office — to “authorize women, on terms of quality with men, to exercise all the rights of citizens.” Their plea, of course, went nowhere. It was filed away until Topich uncovered it.

Now that the petitions are digitized, said Carpenter, historians and social scientists can do more than read them. Using metadata, the documents can be compared across locations and time periods. Signatories can be analyzed, he said, to reveal treelike social networks. Such aggregating, comparative techniques for digital humanities scholarship will provide perspectives not possible by working with the physical documents. Eventually, he said, by using volunteers in a crowdsourcing universe, each petition — even each signature — will be transcribed.

Data aside, the sheer rhetorical power of these petitions, like the oratory of Angelina Grimké, still resonates more than a century later. Who has heard of Sarah E. Wall, a self-described “taxpayer in the city of Worcester”? Likely few of us. But Wall wanted to be heard, and now — through the magic of the digitization — she is. In one 1857 petition, Wall appealed to the Massachusetts legislature to give women full citizenship so as not to “defraud the world, by excluding from its councils, the powers and experience of one half the human race.”

The database, distributed by the Harvard Dataverse Network, became available earlier this week. The prospect of such searchable digital documents, along with images and metadata, excites scholars like Knight, whose previous work includes two books on pioneering social activist Jane Addams. “They discovered petitions,” she said of Carpenter and Topich, “that everyone thought — that I thought — were lost.”

It was these petitions that opened new worlds to 19th-century women to whom the civic arena was otherwise closed, said Knight. “Petitioning returned their political voices. It was the one legal means they had” for expressing their views and desires and demands.

That legal means, Knight told her audience of 50, was in full flower during the summer and fall of 1837, when the Grimké sisters were hired as agents in a Massachusetts anti-slavery campaign. The number of petitions signed that year more than doubled compared to 1836; the number of anti-slavery societies in the state nearly doubled, to 47.

The Grimké sisters whirled through the state like dervishes, filling churches and halls with record audiences during days that sometimes included three events. Meanwhile, they broke taboos against women speaking to mixed-gender audiences and speaking in public.

In all, Massachusetts in 1837 represented that moment in American history that “made women political,” said Knight. “Something historic happened.”