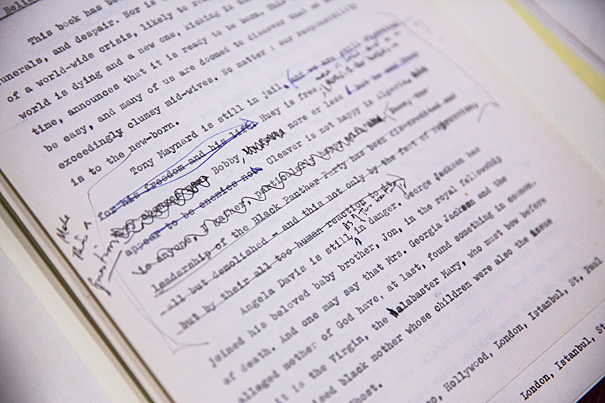

A page from Houghton Library’s James Baldwin typescript of “The Welcome Table” (photo 1). Leslie Morris, curator of modern books and manuscripts (image 2), with the 3,000th item in Houghton’s American collection. Handwritten notes that came with the typescript (photo 3), which was paid for in equal shares by Houghton Library and the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

A close glimpse of James Baldwin

Gates has leading role in history of play acquired by Houghton

Harvard’s Houghton Library recently acquired the 3,000th item in its “MS Am” collection of American manuscripts, literary papers, historical documents, and artifacts.

The first such acquisition, in 1874, was a gift: the 1829-74 correspondence of Charles Sumner — 170 albums in all, said Leslie Morris, Houghton’s curator of modern books and manuscripts. Sumner was a longtime Massachusetts senator and abolitionist who once taught at Harvard Law School, but he is best remembered as the fire-and-facts orator who led the anti-slavery wing of the Republican Party leading up to and during the Civil War.

Given Sumner’s passion for racial justice, it is fitting that MS Am 3000 is a work by a 20th-century writer who spent his life struggling with the culturally embedded forms of racism that survived well beyond the Civil War.

Novelist, playwright, and essayist James Baldwin (1924-87) was a black man who grew up in the racially divided and rancorous America that Sumner once dreamed would soon be history. (In 1870, he introduced what became the Civil Rights Act of 1875, whose language of racial freedom and inclusion sounds modern. In 1883, the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional, lighting the fuse for the Jim Crow era.)

MS Am 3000 is more than the joining of two famous Americans, however. The document, an undated typescript of an unfinished Baldwin play called “The Welcome Table,” includes a central character based on a Harvard professor.

“Peter Davis was me,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr. in a conversation about the journalist who is one of the play’s main characters. Gates — who at age 22 met Baldwin in France — is Harvard’s Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and the director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

Another character in the play — Gates averred, and other scholars agree — is based on Josephine Baker (1906-75), the iconic American dancer who took Paris by storm in the 1920s and ’30s. In her day Baker was as famous as the Beatles, in part for her sensual dance routines and minimal costumes. Starting in the 1950s, she gave her voice to the Civil Rights movement and to the idea of racial inclusion. She dubbed her family of 12 adopted children, racially diverse, “the Rainbow Tribe.”

What brought Baldwin, Gates, and Baker together was an August 1973 visit to the author’s villa in St. Paul-de-Vence in Provence. Gates was a London-based journalist at the time, assigned to a story on black American expatriates. He rented a car and drove Baker from her home in Monte Carlo to Baldwin’s villa. It was a reunion of the aging entertainer and the American author. The meeting was to be their last. Baker died two years later.

In an essay about the meeting, Gates was wry about himself — “with my gold-rimmed, cool-blue shades and my bodacious Afro,” he wrote — and awed both by the company and by the heavenly setting of southeastern France in the foothills of the Alps near the Mediterranean. “The air carries the smells of wild thyme, pine, and centuries-old olive trees,” he wrote.

The setting of the meal itself was a welcome table, which Gates called “a metaphor from the black sacred tradition. It’s where the good go when they die and go to heaven.”

That welcome table was also the spark that gave the play the shape it has in the Houghton typescript and in the other surviving drafts. “There was only one night Josephine Baker was brought to James Baldwin’s house,” said Gates. “He wrote it because of that night.”

In his essay, “The Welcome Table: James Baldwin in Exile,” Gates wrote that his personal day of awe in France had its origins at a church summer camp in West Virginia when he was 14. An Episcopal priest from New England had loaned him a copy of “Notes of a Native Son” (1955), Baldwin’s first work of nonfiction. “It was the first time I had heard a voice capture the terrible exhilaration and anxiety of being a person of African descent in this country,” Gates wrote. “The book performed the Adamic function of naming the complex racial dynamic of the American cultural imagination.”

Gates’ visit to Baldwin was central to the play. But the full origins are more complex. For one, Baldwin had started a version of the play in 1967 when he was living in Istanbul. Its thematic threads survive as a meditation on sex and gender, but “The Welcome Table” of the early conception had a rougher edge. It was to be a “drawing-room nightmare,” Baldwin wrote, and titled “121 Days of Sodom.” The work evolved after the 1973 gathering, and a black journalist became the catalyst for reuniting old friends.

The four known typescripts tell a complicated story of an author changing his mind. Gates has a typescript copy of his own, in storage. He appears there as a young Peter Davis, he said. But in the Houghton copy Davis is a middle-aged man — old enough to have served in World War II; to have a grown son; and to act as a mentor to Daniel, another writer at the play’s welcome table.

“However old he made me — that’s his business,” said Gates of Baldwin, whom he continued to meet as a friend. The Houghton typescript, he added, “is clearly a revision.” But Baldwin’s own obsessions as an artist and essayist remain in full flower in the Houghton typescript: the black experience, sliding and eliding sexual identities, racial mixing, class divisions, the solace of drink, the hubris of American political power, and the double edge of exile.

In all, “The Welcome Table” mingles Baldwin the fiction writer with Baldwin the essayist. Here, the author’s notoriously (and attractively) complex sentences are bent to the clarity and directness of dialogue.

On the last page of the typescript, two characters stand to one side. One says, with the spacing Baldwin typed out, “Shall — we — drink to the welcome table?” The answer seems to be, from a writer who was near death as he revised the play: “Yes.”

Of the known typescripts of “Welcome,” two have Harvard ties: the one Gates owns and the one at Houghton: 72 pages, with revisions, and a few unrelated pieces, including a poem. The others are at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and in the hands of Walter Dallas, a Washington, D.C., freelance theater director.

Taken together, the drafts present a tangle of directions and intentions. The

Houghton copy contains numbering changes, inserted pages, and two different types of paper, suggesting different intervals of revision. To unravel all this will take the eyes of a Baldwin scholar. It is, said Morris, “an obvious project for someone to take on.”