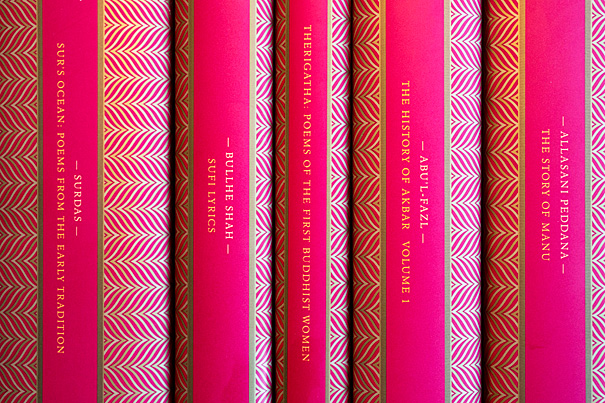

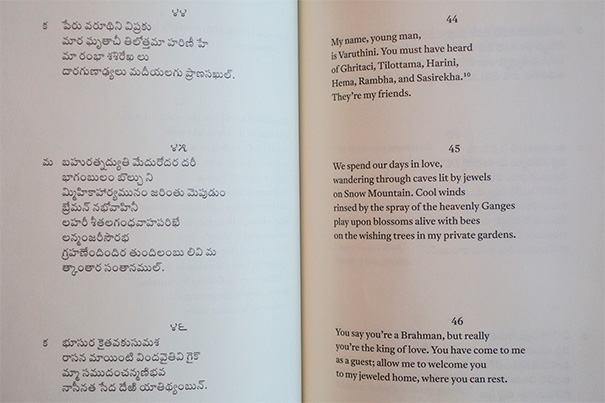

The first five volumes of the new Murty Classical Library of India (photo 1) were released in January from Harvard University Press. The hope is to publish 500 volumes over the next century, which will reveal to the world a “colossal Indian past” of multilanguage literary history from as far back as two millennia. A detail from Volume 4, “The Story of Manu” by Allasani Peddana (photo 2). This is the first time it has appeared in English.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

A literary colossus

Scholars celebrate publishing first five volumes keyed to India’s cultural past, the first of 500 in the next century

In the spring of 2009, Sheldon Pollock ’71, Ph.D. ’75, the Arvind Raghunathan Professor of South Asian Studies at Columbia, was sitting in a Cambridge café with Sharmila Sen ’92, executive editor at large at the Harvard University Press. “I took out the proverbial napkin,” said Pollock. The two sketched out what would be needed to publish his longtime dream: a series of volumes on classical Indian literature.

Why not 500 books over the next century, they thought: poetry, prose, philosophy, and literary criticism — and later science and mathematics? These largely unseen works, some of which date back more than two millennia, had in the last century shrunk to a canon available almost solely in Sanskrit.

Such a visionary series could bring to light again the heart of the longest continuous multilanguage literary tradition in the world, one that represents the most languages, at least 20 of them. The many languages of the Indian subcontinent, both living and dead, are a musical linguistic litany that includes Sanskrit, Prakrit, Pali, Marathi, Sindhi, Hindi, Tamil, Persian, Telugu, Urdu, Panjabi, and Bangla.

Why not a new series? A model format was already in place. The Loeb Classical Library, launched at Harvard University Press in 1911, now comprises more than 525 handsome volumes in Latin and Greek, along with solid English translations on facing pages. “Back when I was 19 or 20,” said Pollock during a phone conversation, “I very much thought a classical library for India along the lines of the Loeb was a terrific idea.” He called the series an object of “wishing and longing” for decades.

Wishing, longing on a napkin

Sen remembers the same day, when wishing and longing was sketched out on that café napkin. “Shelly told me about the idea,” she said. “I liked it very much. It was exciting to us both.” Sen, who was raised in Kolkata and has a Ph.D. in English from Yale, was aware of a publishing precedent, the Clay Sanskrit Library published by New York University Press, which stopped at 56 volumes.

Its benefactor, investment banker John P. Clay, a onetime honors student at Oxford who studied Avestan, Sanskrit, and Old Persian, died in 2013. (Pollock was co-editor and then editor of the Clay Library.)

A new library of Indian classics, Sen said, would represent all the old languages, including Sanskrit. It would feature attractive and literary translations into English. And it would use the appropriate Indic script on the left-hand page. (The Clay series uses transliterations in Latin script.)

The napkin was full. The idea was good. But where might the money come from to bring it to life? The project, which Pollock described as “the most ambitious ever taken on by an American university press,” needed an endowment, said Sen. “The marketplace doesn’t support these kinds of books.”

Enter Rohan Narayana Murty, with whom Sen and Pollock met in the fall of 2009, when Murty was a Harvard Ph.D. student in computer science. “We had one meeting,” she said. It was enough to convey the series idea and the money it would require. Immediately apparent, she said, was that “this was something very important to Rohan.”

Murty is the scion of a wealthy business family in Bangalore, India, with a history of educational philanthropy. His father is the information technology industrialist N.R. Narayana Murthy, co-founder of Infosys. His mother is the polymath computer scientist, social worker, and author Sudha Murty, India’s best-selling female author, with 136 titles to her credit.

Rohan Murty, now on leave as a junior fellow in the Society of Fellows, knew about the Loeb series, of course, said Sen, and wondered why there wasn’t a version for Indian literature. During his graduate studies at Harvard, Murty took a break from distributed computing and opportunistic wireless networks to delve into courses in the Department of South Asian Studies with Parimal G. Patil, professor of religion and Indian philosophy.

Then came the conclusion of what Sen called “a series of happy accidents,” beginning with that napkin sketch. In 2010, Murty founded the Murty Classical Library of India with a gift of $5.2 million to Harvard.

Hope to publish 500 titles

The first five volumes of the series came out in January. (Pollock, general editor of the new library, is part of a four-person editorial board.) Within the next century, insiders hope that the MCLI, as they call it, will publish at least 500 titles.

“In many cases, you’re getting the first translation” of a work, said Sen, “and the first modern critical edition.”

It’s a massive undertaking. “The world of classical Indian learning is very small,” said Pollock, but at least 40 more volumes have been commissioned already. No one has turned down an offer yet to be part of the MCLI, he said. “It’s quite an extraordinary opportunity for us classical Indian scholars.”

The participants hope the series will introduce a vast corpus of literature, thought, and science to fresh audiences across the world. The languages represented in the series will appear in their original script, or in Latin script where appropriate. (Every new Indic font can be downloaded free, for non-commercial uses, once the font has appeared in print.)

The cursive Indic fonts appear fanciful and fascinating to the average reader of English, resembling a decorative collection of lexical pictures. But Pollock thinks that a new generation of Indian-language scholars will emerge as they are intrigued by the appearance of these pre-modern languages in their original scripts. He said that learning the scripts and translations will be helped by the ease of reading from one side of a page to the other.

In a future electronic edition of the works, said Pollock, a scholar will be able to “toggle between scripts,” smoothing the way to compare one old script to another.

The volumes, present and planned, include a lesson in geography. The languages reflect places beyond modern-day India. They represent an area far larger than Europe — stretching west to Afghanistan, east to Myanmar, and north and south from Nepal to Sri Lanka.

“It’s completely transformative,” said Patil of the new series. “It makes it possible to take courses in classical Indian literature” as readily as courses in the classics of ancient Greece and Rome.

With a horizon of a century hence, “this is a project for people’s children and grandchildren,” said Patil, who chairs the MCLI’s oversight board. Executing the idea meant challenges, including “good readable English translations,” rather than some past renderings that were scholarly but dull, he said. “You didn’t want to read them for pleasure. You can’t see the beauty.”

Sampling the first five volumes turns up English translations that are exuberant and thrilling, and that illustrate literature’s uncanny ability to make the foibles and obsessions and heartbreak of the past echo those of the present. “What does being a woman have to do with it?” a Buddhist nun wrote in a poem 2,600 years ago. “What counts is that the heart is settled / and that one sees what really is.”

A launch event at Harvard

Since the first books appeared, Pollock and Sen have attended a series of events to launch the new library, including three in India and one in London. The fifth and final launch event is slated for Thursday (March 5) at the Harvard Art Museums. “Shelly’s old professor will be there,” said Sen. That is 79-year-old Glen W. Bowersock, who Pollock recalled canceled a class during the antiwar tumult at Harvard in May of 1970, after reciting a sympathetic line from the historian Tacitus.

“These works are not just for scholars,” said Sen. They follow the model established for such libraries by James Loeb himself, Class of 1888, who wanted to be a professor of classics. Because he was Jewish, the doors to academe were closed to him in that era. Instead, Loeb funded the classics library that bears his name and was designed to appeal both to scholars and the public.

“He wanted this knowledge of classical literature to extend beyond university walls,” said Sen. The same will be true of the MCLI, she added.

In India, paperback versions of the MCLI will retail for the equivalent of $3 to $5, depending on the volume’s size. “We’ve spent a lot of time figuring out how to sell books in India,” she said, in ways “that are affordable to students.”

Sen did her honors thesis at Harvard on James Joyce. She and Murty “know our Shakespeare and Milton and Wordsworth, our Emerson and Thoreau,” she said. Both wanted to fill in the gaps of available classics from their own culture. “Maybe for future generations in India,” she said, “it will be part of the standard curriculum.”

The curriculum throughout India covers English literature, said Pollock. “Nowhere in India are Indian classical texts a normal part of the course of study.”

In an interview with an Indian newspaper last fall, Murty said the MCLI would fulfill a dream of his own for India, “to bring a colossal Indian past to its present.”

Volume 1 of the MCLI, in Panjabi, is “Sufi Lyrics” by Bullhe Shah, an 18th-century practitioner of this mystical poetry tradition. He wrote not long before the British conquest of Panjab in the 1840s, the beginning of a colonial cultural wave that submerged much Indian literature. The verse is pan-religious, and threaded with humor and optimism. “This flower bed of earth is wonderful,” Shah writes in one verse. “Earth goes strutting along, my friend.”

Volume 2 is “The History of Akbar,” the first of seven planned volumes. It’s a grandiose 16th-century rendering in Persian of the life of the Mughal emperor Akbar, who presided over an era of religious tolerance. His bloodline, author Abu’l-Fazl asserts, began with Adam; Akbar’s birth was accompanied by miracles; and his life was suffused with divine light. (“That Akbar is related to the sun,” he wrote, “is obvious.”) This work, a model for historical prose in its day, has appeared in English translation only once.

Volume 3, the most slender, gets a lot of attention for being a translation of what is likely the first collection of women’s writing in the world. “Therigatha: Poems of the First Buddhist Women,” written in the Pali language by elder Buddhist nuns in the fourth century B.C.E., is also the oldest work among the first five volumes.

Pali, the ancient language of Buddhism, disappeared from mainland India in the sixth or seventh century, along with manuscripts in the original Indic script, said Pollock. Pali works survived in other languages and are still studied in Buddhist communities outside India. In the West, these poems are commonly printed in Roman typeface. Many had been widely translated, but “this is the first translation of this book that really works,” he said.

The poems, often cast as advice to younger women, are morally acute, closely observed, and keenly social meditations on sex, children, aging, and death. The language of these women has a characteristically Buddhist bluntness in the face of impermanent life. One verse reads:

Once my thighs were beautiful,

Like the trunk of an elephant,

Now because of old age,

They are bamboo sticks.

Volume 4, appearing for the first time in English, is “The Story of Manu” by Allasani Peddana, who called himself the originator of Telugu poetry, though such poetry had existed 500 years before. But Peddana did something new, however. His work is more lyrical and sound-driven, and it recreated Telugu poetry as a private experience instead of a shared public reading. Peddana used prose when verse no longer seemed rich enough, and he was a naturalist in an age when close observation of nature was prized. “They’re rough and fat,” he wrote of wild boars. “You want to know how strong they are? / They bend back thick stalks of bamboo / with their snouts, as if they were flimsy as maize.”

Volume 5, the thickest, is “Sur’s Ocean: Poems from the Early Tradition” in the style of Surdas, the poet laureate of the Braj Bhasha language at the end of the 16th century. Within in less than 100 years, by one account, there were 125,000 such poems, an “ocean” of Sur that one scholar drained to a minimalist canon of about 5,500 works. Four decades in the making, the volume of 433 poems appears here for the first time in English. (Pollock drew on scholarly works done or nearly done for two of the first five MCLI volumes. The others were specially commissioned.)

Holding the Surdas genre together were tales of Krishna, the cowherd deity of Hindu tradition. He is one of many figures familiar to Indians in everyday storytelling, though largely unavailable in printed literature. The MCLI, said Patil, will fill in gaps between common imagery in India and the works that gave rise to it.

Outside South Asia, MCLI volumes will be welcoming for a wider English-language readership, said Pollock. Each will have an annotated, footnoted, well-introduced guiding apparatus, which is important for understanding old literature so new to so many readers. At the same time, “the hope is that many of these books will be shocks of unfamiliarity,” said Pollock, and will require “the reader’s willingness to be completely surprised.”