The revamped Harvard Design Magazine made a splash at a recent launch event, which gathered Guest Editor Pierre Bélanger (from left), Editor in Chief Jennifer Sigler, and Associate Editor Leah Whitman-Salkin. The current issue, “Wet Matter,” offers a view from the oceans.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Making print modern

New look for Harvard Design Magazine deepens focus on ‘Wet Matter’

In an age of bits and bytes and pixels and text on screens, Harvard Design Magazine — relaunched in a new format last year ― fervently embraces the thingness of print, the quotidian actuality of paper and ink.

The right wordsmiths were on hand to recast and renew the magazine, which is produced at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Editor in Chief Jennifer Sigler, who made books by hand as a child, was the editor behind “S,M,L,XL” (1995), a 1,376-page compilation of Office for Metropolitan Architecture essays, diary entries, and photographs by Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau — a book so popular so fast that it was counterfeited in China. “The act of turning pages has always been important,” said Sigler of her enduring fondness for print in a 2009 interview. “There’s drama in that ― suspense, engagement. It’s physical.”

Associate Editor Leah Whitman-Salkin is another champion of the magic of ink on paper. Prior to joining the magazine and the GSD, Whitman-Salkin was the editor at Sternberg Press, a leading independent art and critical theory press based in Berlin, Germany. With the redesigned magazine, she said last week, “We recommitted ourselves to print.”

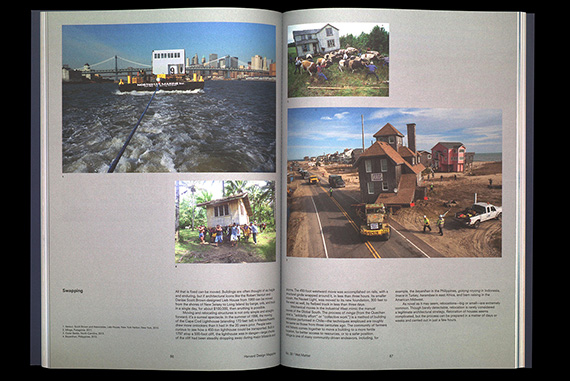

Issue No. 39, F/W 2014, is “Wet Matter,” a 175-page, multi-essay, lushly illustrated exploration of what Guest Editor Pierre Bélanger describes as “the other 71 percent” of the world: that is, the oceans. Bélanger, an associate professor of landscape architecture and a close student of this “ocean nation,” calls the seas “a glaring blind spot in the Western imagination.” The oceans make up a “vast logistical landscape,” he writes, to which designers are just awakening “as sewer, conveyor, battlefield, or mine.”

In her own brief essay, Sigler — a veteran of the architecture world for two decades ― asks of designers and citizens alike, “Why this insistent focus on the dry?”

Assembling the issue, she said, included “weekly or biweekly personal seminars with Pierre” that got down to the details of what he called “the ocean as contemporary urban space.” In a conversation with Sigler and Whitman-Salkin at a launch event March 6 at Loeb Library, Bélanger admitted, “I was a bit of a geek.”

But he also sang the praises of the magazine format, editorial turf that exists somewhere between the ephemera of the blogosphere and the restrictions of peer-reviewed publications. “To be honest,” he said, “it was totally liberating.”

The “Wet Matter” issue, said Bélanger, turned into an exercise on “how far you can stretch out an idea.” The content ― 33 illustrated essays and interviews, along with five reviews — proves that point by being eclectic and surprising. The mix of typefaces alone keeps the reader pleasingly off-balance.

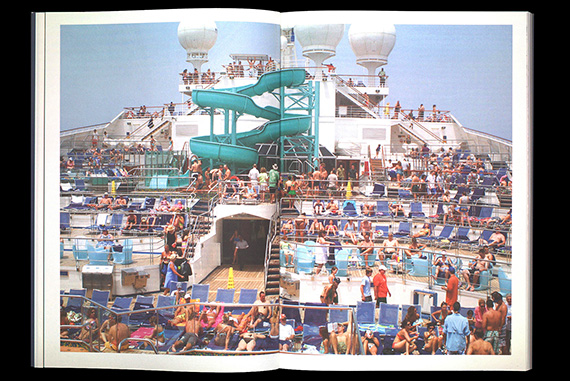

Consider just a few points raised in the essays: that marine algae are “the densest biologic entity on the planet” (from a piece on seaweed by Catherine Seavitt Nordenson at City College of New York); that the human body, mostly porous and wet, is simply one among many “bodies of water” on the planet (Helsinki-based writer Jenna Sutela); and that the cruise-ship industry, which has grown 4,000 percent since 1970, is at the center of a “terrorism of tourism” that widens disparities between the worry-free “floating worlds” of giant ships and the increasingly dispossessed foreign populations they visit (from an architecture and urban research collective in Rotterdam called Supersedaca).

Add to all that reports and meditations on fishmeal, invasive marine species like the sea squirt (the author, a chef, suggests eating them), building on sand in Singapore, the Panama Canal, “soft” buildings that adapt to storms and sea-level rise, and a movingly annotated reprint of “Undersea,” a 1937 Atlantic Monthly essay by Rachel Carson.

“Who has known the ocean?” Carson wrote. “Neither you nor I, with our earth-bound senses. …” Like Bélanger’s plea to consider “the other 71 percent,” the essay is an invitation to look again at the oceans, from the tide pools at water’s edge to the undulating, prairielike floors.

The interviews in No. 39 also challenge and teach. Not content with calling on only the usual set of experts, the editors sought interviews with an oceanographer and a poet, and another with an activist physician from Women on Waves.

Oceanographer Xiaowei Wang interviewed ocean scientist Dawn Wright on mapping the oceans and how the dynamic elements of that topography defy most conventions of what makes a borders. Detailed maps are possible by using sound waves, but only “at the speed of a bicycle,” he said ― unlike the low-Earth orbit satellites that can map land at 15,000 miles per hour.

There is also an essay by German sociologist Ulrich Beck, “How Climate Change Might Save the World: Metamorphosis,” which defies the often apocalyptic tone of climate change literature. Beck, in what would be his last essay (he died in January), wrote that the need for global cooperation might occasion “transfiguration of world power structures.”

Graduate student Héctor Tarrido-Picart interviewed poet Victor Hernández Cruz about “fluid landscapes.” It may be the only design magazine article to discuss, if briefly, the cha-cha-cha.

“I read for a month” before the one-session Skype conversation, said Tarrido-Picart. He also studied the interview style of NPR’s Terry Gross.

In all, the magazine format is ideal for mixing eclectic views on a single theme and for interdisciplinary pursuits, said Sigler. “We realized a magazine could be a powerful tool for bridge-building.”