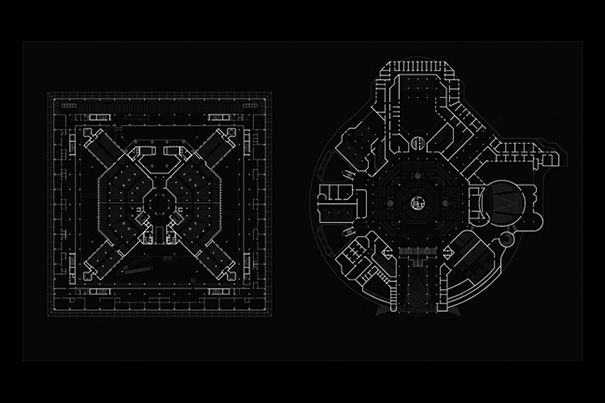

An architectural photo from “Dualisms: Abalos + Sentkiewicz” in the main exhibition space at Gund Hall.

Photo by Justin Knight

Stages of design

Movements in research and learning captured in trio of exhibits

You are hiking in the Julian Alps of northwestern Slovenia. Suddenly bad weather closes in. Blinding snow, high winds, frigid temperatures, even the risk of avalanche. You need shelter. What might it look like?

Students at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) confronted that problem in the fall in a studio course called “Housing in Extreme Environments.” They imagined, drew, and created models of a variety of structures. The design parameters for the alpine shelters: house up to eight people, use little energy, and be light enough to be set in place by helicopter.

The models are now featured on the Experiments Wall in Gund Hall. When you see the exhibit, be sure to pull out the drawers underneath to get a sense of how design problems unfold from math to drawing sets to models. “We wanted to show the depth of research, and how it manifests itself in different media,” said Dan Borelli, GSD’s director of exhibitions. The winning design looks like a robust succession of compact A-frames capable of withstanding the irregular stresses — “loadings” — imposed by high winds and heavy snow.

The “Extreme Environments” exhibit, which represents emerging pedagogy, was launched in a mid-February lecture and closes March 22. It’s curated by the studio’s instructors: Slovenian architecture partners Spela Videcnik, the John T. Dunlop Design Critic in Housing and Urban Development this year, and Rok Oman, a GSD lecturer in architecture.

The exhibit is one of three continuing this month on the first floor of GSD’s main building. The others also illustrate common GSD exhibit themes: proposed research and a single design concept.

The exhibit on proposed research, “Icons of Knowledge,” is in the Loeb Library space. It explores the intriguing design and symbolic commonalities among national libraries worldwide.

In Gund Hall’s main exhibition space, “Dualisms: Abalos + Sentkiewicz” — closing March 8 — is based on thermodynamic design, a concept that focuses on the heat effects of materials and sites; on temperature control, including passive systems; and on the energy used to both build and maintain a structure. Among architects, it complements the concept of sustainable design, where the focus is on renewable materials. “Dualisms” introduces three professional projects — one built, one not built, and one in process. They are from the firm of Inaki Abalos, a professor in residence and the chair of the department of architecture, and GSD Design Critic Renata Sentkiewicz.

Conceptual and working drawings — layered and colorful — dominate the exhibit. “If you want to get these kinds of structures built,” said Borelli, “you have to draw — draw them very thoroughly.”

The presentation includes table models, a staple of architectural conceptualizing. One shows China’s Zhuhai Huafa Contemporary Art Museum, complete with a courtyard sheltered by tall artificial trees that resemble giant, spreading, silvery ferns.

To the casual viewer, the exhibits may seem to clash. But GSD exhibits are always expressions of collaboration, experiment, and faculty-student interplay, said Borelli. “We think very carefully about these juxtapositions.”

“Icons of Knowledge” captures another dynamic often found behind GSD exhibits: the evolution of a project through tiers of engagement. Project curators Noam Dvir, M.A.U.D. ’14, and Daniel V. Rauchwerger, M.Des. ’15 — both from Tel Aviv and both former journalists — first explored the idea in a piece in Harvard Design Magazine. It grew into an independent project, and then into the exhibit, which will soon have a second life as a traveling exhibit. (The Loeb show closes March 22.)

“This is a continuation of our life in school,” said Dvir, who has partnered with Rauchwerger to form the architecture, media, and design practice We Are Young Architects. The exhibit is also a way to exercise a goal of their practice, he said: to mix media and architecture.

The effort began with a database of the world’s national libraries, including grand structures from the 17th century, 21st-century designs, and sheds in sub-Saharan Africa. Among the more established national libraries, the collaborators “found a form that persists” across culture, time, and geography, said Dvir: a rectangular central reading room “where knowledge is both collected and created.”

From the center outward, other conventions often emerge. In the exhibit — comprised of models, along with a 36-foot mural with 40 drawings — the national libraries of Greece, Bulgaria, Brazil, and Australia, for instance, all use the same style of both portico and entrance.

Meanwhile, library exteriors represent national aspirations in a variety of culturally determined styles. In Saudi Arabia, the façade of the national library is veil-like. In Kosovo, the library is topped with 99 domes, and has no front or back — “a radical design,” said Rauchwerger. But inside, the typical central plan persists.

National libraries are still being built at a rapid pace despite the emerging hegemony of the digital age. They remain chiefly expressions of cultural identities. But at the same time, said Dvir, they represent “an extremely interesting case study of the way that architecture is global.”