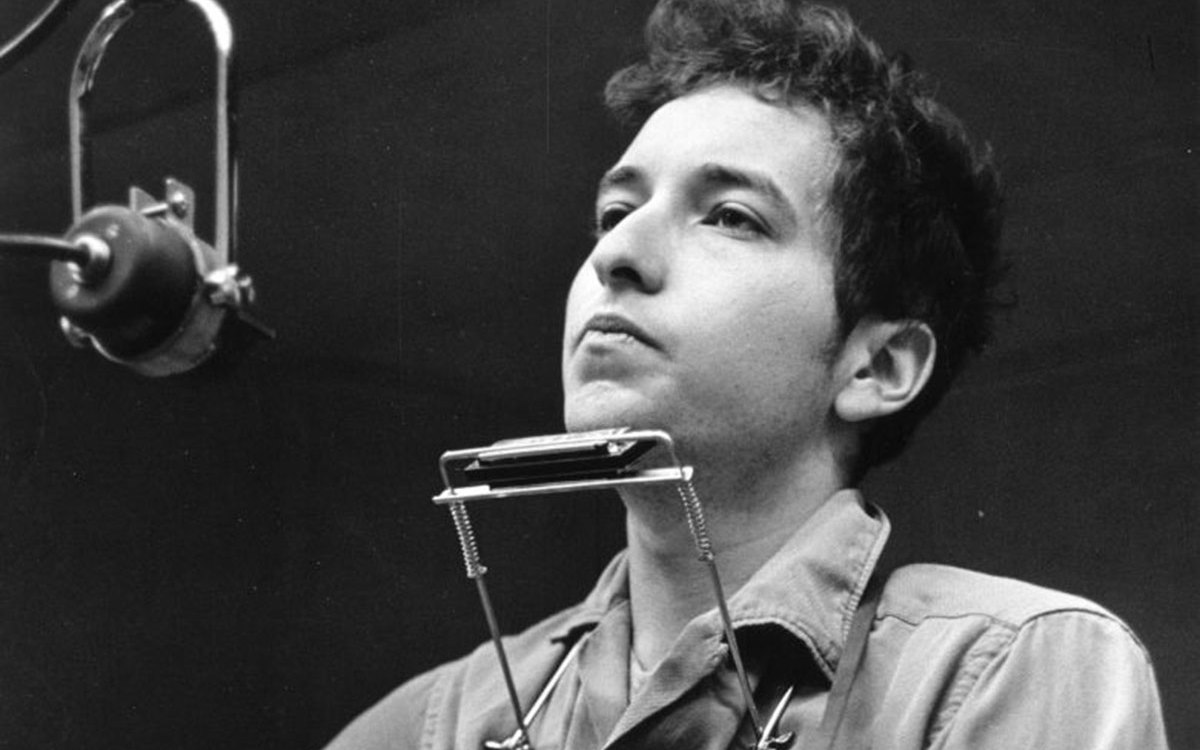

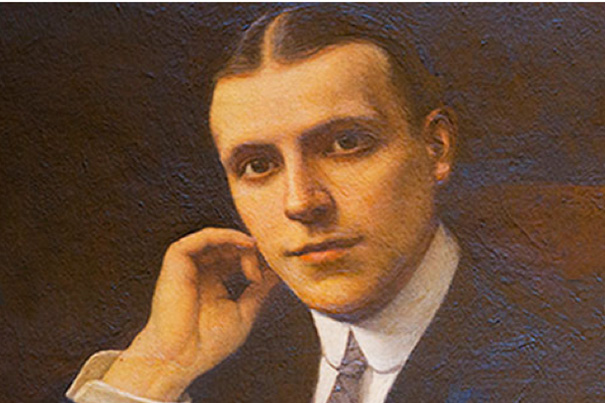

There will be a yearlong celebration of Widener Library, which turns 100 this June. This painting of Harry Elkins Widener hangs over the fireplace in the Widener Memorial Room. Launching the celebration were two lectures. John Stauffer (photo 2), a professor of English and African and African-American Studies, talked about the value of Harvard’s collections. Leslie Morris (right, photo 3), curator of modern books and manuscripts at Houghton Library, shared the stage with Stauffer. In her talk, Morris offered a glimpse of book collector Harry Elkins Widener, outlining his acquisitions. Among his books were first editions of Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Celebrating Widener

Lectures look ahead to library’s centennial

Harvard’s Widener Library ― with its 57 miles of shelves, labyrinthine floors, and millions of books ― will mark its centennial on June 24.

When it opened on Commencement Day of 1915, Widener ― tall and wide and deep underground ― replaced Gore Hall, an 1841 Gothic structure with wedding-cake spires and drafty rooms. Gore was declared full in 1863, so 52 years later, the 320,000 square feet of Harvard brick and Indiana limestone that made up Widener seemed heaven-sent. It was and still is the largest university library in the world.

To celebrate the centennial, library officials could not wait until June. Two lectures on Thursday marked the beginning of a yearlong series of events and exhibits about Widener and its mysteries, history, and marvels.

Both talks were in the Forum Room at Lamont Library.

Leslie Morris, curator of modern books and manuscripts at Houghton Library, offered a glimpse of book collector Harry Elkins Widener, the library’s namesake and a member of the Class of 1907. He had bought his first serious acquisition as a college sophomore in 1905: a third edition presentation copy of “Oliver Twist.” It set the teenage Widener back $200 ― $5,500 in today’s dollars.

John Stauffer, a professor of English and African and African-American Studies, talked about the value of Harvard’s collections.

He also talked about how Boston and Harvard collections were influenced by a pair of unlikely 19th-century Boston friends: radical abolitionist Charles Sumner and conservative merchant George Livermore, both of them bibliophiles. Stauffer is at work on a biography of Sumner, a 23-year senator he called the “preeminent intellectual in Congress” in the time of the Civil War.

Widener, whose wealthy Philadelphia grandfather had amassed a fortune in oil, steel, and streetcars, perished in the Titanic disaster 103 years ago this month. By the time of his death at 27 — he had been in London on a book-buying trip — he owned 3,300 collectable volumes, all of them now housed at the library that bears his name.

Morris outlined his acquisitions, the escalating prices he paid, and the “all-embracing” collection he left behind. Among his books were first editions of Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson; Shakespeare folios; illustrations by George Cruikshank; costume books inspired by his days at Hasty Pudding; and ― a favorite, said Morris ― a copy of Philip Sidney’s “Arcadia” that had been owned by his sister, the Countess of Pembroke, an author who inspired her brother’s 16th-century masterpiece.

Legend has it that Harry Widener died with a rare 1598 copy of Francis Bacon’s “Essays” in his tuxedo pocket, one of the nine books he had just bought in London. (The other eight had been safely shipped home.) There is a copy of the same edition in the Widener rotunda, on display through June. Why it was called “the little Bacon” is obvious: It’s barely the size of a baseball card.

Tiong Lu “John” Koh L.L.M. ’85, a book collector and investor, remarked on the poignancy of the volume lost at sea with Widener, “in one of the best book anecdotes ever.” It was Bacon, after all, he said, “who referred to the ark of learning” ― the great vessel full of books that a library represents.

Koh owns Bernard Quaritch Ltd., London-based antiquarian booksellers since 1847. The company was well known to the young Widener, and supplied some of the items on display. One is a bid book listing collectibles Widener wanted to buy at a June 1915 auction.

In the same case is a faded telegram from the young collector’s book dealer and friend A.S.W. Rosenbach, a shrewd bidder who considered the Harvard graduate his protégé. “Harry Widener and father lost titanic,” it reads. “Mrs saved.”

“Mrs” was Harry’s mother, Eleanor Elkins Widener, who climbed aboard Lifeboat 4 with her maid and survived the sinking. She funded Widener in her son’s memory.

So a shadow lies over this 100th birthday. It took a fated ship to go down for a fêted library to go up. At the 1915 dedication, Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge added perspective. “Great deeds,” he said, “can arise from tragedy.”

Great deeds, as Stauffer pointed out in his lecture, can also arise from friendship. Together, Sumner and Livermore, who met in 1844, were among the most prominent champions of public libraries in the mid-19th century. Within what Stauffer called a “bibliophilic friendship,” they insisted that libraries be free, public, and accessible.

Sumner’s voluminous correspondence ― 170 albums of letters ― makes up MS Am 1, the first installment of Houghton’s American collection. He was a believer in the power of that era’s Harvard library, said Stauffer. It was regarded then as a public library, famously so.

The self-educated Livermore, a dry goods merchant who made a lot of money in wool, leather, and shoes, “is almost entirely forgotten today,” said Stauffer. But before his death in 1865 he had amassed one of the most impressive collections of books and other artifacts in America. The late-in-life abolitionist whose published research in 1862 influenced Lincoln’s draft of the final Emancipation Proclamation eventually owned the pen the president used to sign that iconic document. It is now among the collections at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Livermore also famously possessed one of two known copies of “The Souldier’s Pocket Bible” (1643), distributed to troops by Oliver Cromwell during the English Civil War.

Both men ― whose bond eventually coalesced around the injustice of slavery — saw libraries as “indispensible to all members of a republican society,” as Livermore once wrote Sumner. In sum, the two men shared a catholic vision of libraries that Harry Widener himself would have agreed with, and Eleanor Elkins Widener envisioned, too: as sites of collaboration and learning.

On the day of Widener Library’s dedication in 1915, she said: Let it become “the heart of the university.”