In Peru, progress against TB

Branch of Partners In Health has helped reduce deaths through careful protocols

LIMA, Peru — On a foggy July morning in a shantytown on the outskirts of Lima, Peru, Hilda Matos waited impatiently for the nursing technician who gives her daily injections and medicine to treat the disease that has had hold of her for the past eight years.

A mother of four and a former housemaid, Matos, 44, has extremely drug-resistant tuberculosis, an ailment that until recent years was considered a death sentence.

But through pioneering work developed by Socios En Salud, the Peruvian branch of Harvard-supported Partners In Health, which began treating multidrug-resistant TB with a community-based model, Matos’ fate can be different.

“I was dying,” she said. “I was so sick I couldn’t eat or move. And when people came to help me, that gave me support and strength to fight off the disease.”

What changed Matos’ prospects was a novel protocol in which trained community health workers visit patients in their homes to make sure they take their medication until they are cured.

The protocol was something that Paul Farmer, co-founder of the nonprofit Partners In Health and the Kolokotrones University Professor of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, had used in rural Haiti. It proved effective in the slums of Lima, too. Patients recovered under the attentive eyes of community health workers. Previously, treatment for multidrug-resistant TB in developing countries was nonexistent, and many patients were left to die. The World Health Organization has adopted a treatment plan based on Peru’s example.

Recruiting health workers to help fight drug-resistant TB in its two forms, multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extremely drug-resistant (XDR), has been the group’s main contribution, said Leonid Lecca, physician and executive director of Socios En Salud.

Socios En Salud in the community

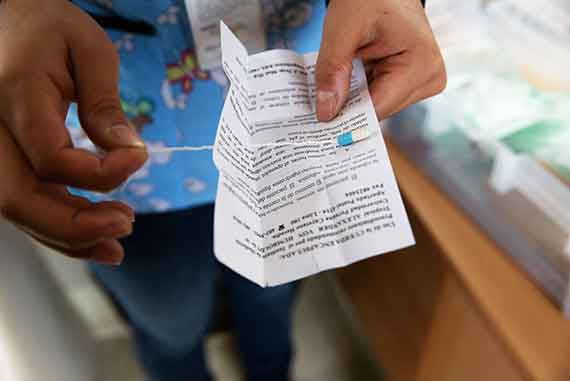

Community health worker Bertha Huaman prepares an injection of capreomycin, a drug used to treat XDR-TB, as part of the program to provide aid to patients in their homes. Photos by Alonso Chero

Carabayllo, the shantytown in Lima where Socios En Salud started its pioneering work 19 years ago treating multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Using a community-based model since 1996, the organization has helped more than 10,000 MDR-TB patients.

To improve TB diagnosis among children, the organization launched pilot DETECT-Niños. A probe placed in a child’s stomach to collect saliva helps doctors detect TB.

Parents Rebeca Cruz and Angel Reyna with Rafael, the youngest of their three children. A community health worker trained Rafael’s parents in how to stimulate him through reading, singing, and playing.

Reyna Cruz, 2, overcame his shyness and language delays after he received help from Socios En Salud as part of an early childhood development program. Like his brother, Rafael, more than 120 children at risk of developmental delays have been helped by Project CASITA, a program Socios En Salud started in 2013.

“It’s a model that saves lives,” said Lecca in an interview at the headquarters of Partners In Health in downtown Boston, where he came for training in July. “Fighting TB is not just taking pills. It’s fighting poverty.”

In Peru, where a third of the population of 30 million lives in poverty, every year tuberculosis affects 33,000 people and kills 4,000. Of the affected, 1,200 cases are MDR TB and about 80 are XDR. In 2010, Peru had the highest number of multidrug-resistant TB cases in the Americas.

Although over the years the number of deaths from tuberculosis in Peru have declined and detection and access to treatment have improved due to the work led by Socios En Salud, there is still much to do. Despite Peru’s booming economy that has lifted thousands of people out of poverty and into the middle class, tuberculosis is far from conquered.

In Carabayllo, the impoverished district where Socios En Salud started its revolutionary work 19 years ago, TB cases are on the rise. To eliminate tuberculosis in the district, the organization launched the TB Zero program a few weeks ago with the support of the local municipality.

“Overcoming TB is not just an NGO’s job,” said Arturo Tapia, another physician working with Socios en Salud. “It’s everybody’s job.”

To help cure patients, the organization provides free medication, food coupons, and even small business training and micro-credits to help patients make a living. Sometimes, patients have their modest houses remodeled to make sure they meet sanitary conditions.

The group has joined forces with the Peruvian Ministry of Health to treat multidrug-resistant TB. It’s a partnership that allowed Peru in 2012 to achieve a higher cure rate in MDR TB (75 percent) than the rest of the world had (48 percent), according to the World Health Organization.

Even driver Javier Yataco, who has worked for Socios En Salud for 13 years transporting patients from their homes to health centers because they’re too sick to walk, has noticed the changes.

“When I first began to work here, of 10 sick people, only one survived,” he said. “Now it’s the other way around. Of 10, nine survive.”

For Karim Llaro, who is in charge of the programs in Carabayllo, the key to success is the community-based model.

“We offer not only medicines; we offer social and emotional support,” she said. “We assign them a health worker who accompanies them throughout the treatment and is trained to give moral and psychological support.”

At her modest home, perched precariously on a rocky hill, Matos, who’s halfway through her two-year-long treatment, agrees. She greeted Bertha Huaman, her nursing assistant, with a hug and a kiss on the cheek when she arrived (late, because of the traffic jams that clog Lima’s roads).

As Huaman gave an injection to her patient, Matos’ face contorted in pain.

“Before I got sick, there was no pain in my life,” Matos said.

“Don’t feel sad,” Huaman told Matos as the sun came through a window. “Because if you do, the medicine won’t work.”