Author Claire Messud speaks about the art of writing. She is pictured outside her office, one of the places where she writes, in the Bunting Quadrangle at Harvard University. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell

Turns of narrative

For novelist Claire Messud, getting the story down can mean letting it stray

Claire Messud announced her professional intentions at the age of 6, asking for a typewriter for Christmas — because, she told her parents, she wanted to be a writer. It was a prescient request.

Messud is the author of a book of novellas and four novels, including “The Emperor’s Children,” a best-seller about a group of family and friends in New York in the months before the Sept. 11 attacks, and, most recently, “The Woman Upstairs.” She was a 2004-2005 Radcliffe Fellow, and last year joined the English Department as a senior lecturer.

This is the first installment in “Decisions and Revisions,” a series of interviews with Harvard-affiliated writers on how their stories take shape.

GAZETTE: When did you first know you wanted to be a writer?

MESSUD: I always loved stories, and as soon as I realized that making them up was something you could actually do, it was what I wanted.

GAZETTE: You write in the afterword of “The Woman Upstairs” that your mother’s letters taught you how to write. What did you mean?

MESSUD: On both sides my parents came from massively epistolary families. We have in our basement boxes and boxes of letters from my grandparents to my parents. My mother was a wonderful letter-writer, her letters made up of all the things that fill creative writing classes, the things that I am trying to teach young writers about: noticing detail or listening to conversations, listening and just writing it down, just observing. When I went to boarding school my mother would write to me maybe three times a week. And when I lived overseas for years she would write me aerograms. I have many, many letters from her. When I was growing up, I wrote letters like that, too. I would spend my summers as a temporary secretary with an IBM Selectric in somebody’s office, and when there was a lull I would type letters to my friends. … I miss that. I don’t do it anymore.

GAZETTE: Can you describe your writing process?

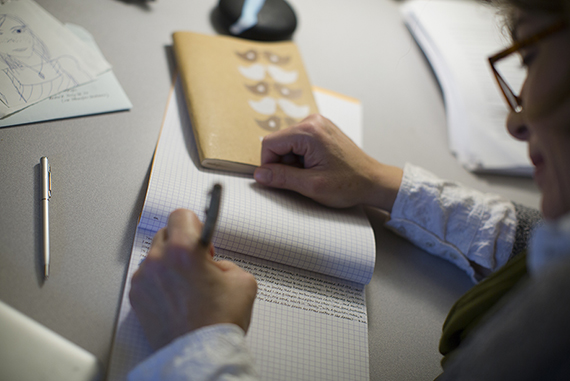

MESSUD: I write by hand. I have all sorts of little, what you would call in French manies, but manias sounds too crazy. I have particular pens and particular paper, graph paper. I write really small, which is a problem now that my middle-aged eyes are failing. The pens that I like best are actually for art, they have a very fine nib, but .05 microball ones will do. But it has to be little, because if you use a fat nib on the small graph paper, then you can’t read it. I prefer a certain kind of paper made by Rhodia, and I get about four typed pages on a page. There are about 70 or 80 pages in a notebook, so you feel like that should do it. It’s always been a book a pad.

‘Even if you have an idea of how you want a piece to end, by the time you have created these people and set them in motion, they have their own laws, their own organic natures, and they don’t always want to fit your ideas.’

GAZETTE: Do you write on both sides?

MESSUD: No, when I make corrections they have to go on the back of the page. There are a lot of stars and arrows and little numbers. And sometimes you realize you want to add something, so in that case, I block off part of the bottom of the page and put a star there. I write articles and book reviews on my computer, but I don’t write any fiction on it.

GAZETTE: Why the separate processes?

MESSUD: Often when I am writing journalism, it needs to get done more quickly. Having been in my youth frequently a temporary secretary, I can type really fast, but that can be a problem because you have something in your head and you type it and you look at it and it’s in a nice font, it looks all but printed, it looks OK. But when I am writing it by hand, I think more carefully about it, it’s just a different rhythm for me. Then it’s there, marks on the page. When I then type it into the computer, I make changes, too. And then I print it out and make other changes on the printed page. But when you write in ink on paper, you know what you’ve changed because you can still see it even if you crossed it out. You know when something was added later. Once it’s in the computer you lose that.

GAZETTE: Is there something that comes easier to you now with your writing?

MESSUD: I don’t know … I am oddly mistrustful of ease. In the process of revision, things have become clearer with age. It’s easier for me to see what’s wrong, not when I’m writing, but when I go back. That doesn’t mean I know how to fix it, but when I was younger I could sense that something was wrong, but I couldn’t say what it was. Now I can see, “You know what, there’s a pacing problem, or this character isn’t on the page.”

I am a great fan and friend of the Australian writer Peter Carey, and I remember him saying at one point to me, about writing books, “If it doesn’t seem impossible, it doesn’t seem worth doing.” The project each time is different, and you never know how to do it. If you knew how to do it before you started, you might not bother.

GAZETTE: How do you know when the work is done?

MESSUD: The first writing is such a visceral thing. The last months of working on a first draft are like when you’re in a European town that you’ve never been to before and you want to get to the cathedral: You can see its spire but you don’t know exactly how far away it is. Maybe you think “it will probably take me a half an hour,” and then, weirdly, it ends up only taking 10 minutes. Or maybe it takes two hours. But when you are at the cathedral you know you are there. And I think with a first draft, which is not revision, I’ve had that feeling numerous times. I know I’m trying to get these things down, but I’m not sure how long it will take or how much it will involve and then I find, oh, I am at the cathedral, here it is.

Revision is really hard, because at some point the deadlines of life play a part. You could keep on revising, you never feel like it’s done. … But then, surprisingly, it turns out that there’s always more time. If you feel it’s not done, people will tend to agree with you. If an editor is pressing you for something and you say, “OK, it’s not ready but here it is,” they will inevitably say, “You’re right, fix that.”

GAZETTE: Is it harder to start or to finish a book?

MESSUD: Good question, hard answer. They are hard in different ways. That’s like saying: Which is harder, takeoff or landing? And as we know almost all accidents take place on either takeoff or landing. Takeoff requires a lot of energy. The thing about landing is, it’s hard to know where to land. Endings are hard because even if you have an idea of how you want a piece to end, by the time you have created these people and set them in motion, they have their own laws, their own organic natures, and they don’t always want to fit your ideas. Nabokov said: Nonsense, you made them up, you move them around. But sometimes the project changes, and what you thought was the end is not going to be the end.

GAZETTE: John Irving has said that he always knows where his books are headed. Do you feel that way?

MESSUD: I am always telling the students, “If you are doing something longer, have an outline, even if you change it. Have some sense of where you’re going.” Like Irving, I know in some way where I want to end up. But I also like E.L. Doctorow’s metaphor that writing is like driving on a country road at night: You know where you’re going but you can’t see beyond the headlights. So even if I know I am headed for Albany, I have to concentrate on what’s in front of me. And I don’t think I’ve ever had the moment of not knowing I was going to Albany, as it were. But what the route to Albany will look like or feel like, or how the characters will relate to one another at any given moment, you can’t always anticipate. It’s not impossible that you would end up in Rochester instead. It could happen.

GAZETTE: Do characters that you create stay with you? Or once the book is finished, do you let them go?

MESSUD: You live with them; they are even in your dreams. And then, when you finish working on the book, you stop living with them in that way. If you’re like me, and you have a terrible memory, you can’t really remember what they were up to. I haven’t picked up my first novel in 20 years. I remember the main characters, but I am not even sure I could say what the minor characters were called. While you’re living with them, they’re these intense presences and then afterwards, they become like college roommates in mid-life: On some level you feel really close, and then on another, you just haven’t managed to get together for a long time.

GAZETTE: Your husband is James Wood, professor of the practice of literary criticism and book critic for The New Yorker. Do you work with him at all?

MESSUD: That, too, is always evolving. In our life before children, there was more time. In life before cellphones there was more time. Early on I would read him bits aloud. He didn’t like being read aloud to. He was always very nice about it but I don’t think he liked it much. Now he’s still my first reader, but not until a manuscript is well along. And we know each other well enough that if I need him just to say “keep going” then I will tell him that outright. But I also really trust him. So if he read something, and he felt, “Don’t keep going, like, really don’t keep going,” he would say so. He did say that once. I had started what became “The Emperor’s Children” and then there was 9/11 and I felt like I couldn’t write it and I started something else. I gave what I had written to him to read, maybe 20 pages. It’s the one time he really said, “No. No, you need to not do that.”

GAZETTE: In an interview with The Paris Review, the novelist Elena Ferrante said: “Literary truth is entirely a matter of wording and is directly proportional to the energy that one is able to impress on the sentence.” What is your reaction to that?

MESSUD: There are lots of ways to think about that sentence or to interpret it. The energy in a sentence is a very interesting and sometimes tricky thing to pin down. There are obvious ways to make a sentence more energetic, in an actual sense, such as eschewing passive constructions — that sort of thing. But the energy of truth, something that rings true, that energy is different. There are aspects of Ferrante’s series [the Neapolitan novels] that have an almost “Downton Abbey” quality, lots of events rolling along, and you think, “Is this too guilty a pleasure?” But in the books, there are also many real truths — about all sorts of things, but I think particularly about girls’ and women’s experiences. These moments have that energy, you recognize it as a reader … if you recognize a work of literature as true, it has an energy and an authority. And as readers, we want more of that. You will read 1,000 pages or you will stay up until 4 a.m. to have that.

If you think of Beckett, Beckett is all truth, with everything else taken out. There is, in his work, tremendous energy, and it’s also painful and difficult to experience, even when it’s funny. When it’s all true, it’s pretty uncomfortable. The poet Glyn Maxwell once said, about the difference between prose and poetry, that poetry is all inhalation, whereas in prose, you need both inhalation and exhalation. The mundane, the digressive — these things are part of prose. It’s prosaic, after all. Part of the rhythm of prose is letting go, part of the truth-telling of prose is in its decompression.

GAZETTE: In 2013 you said during a talk, “So much of what’s important in our lives never breaks the surface.” Do you consider delving into that deeper terrain a writer’s job?

MESSUD: Yes, I think that’s what writing — fiction, literature — specifically is for. For me it’s about what it’s like to be alive on the planet. So much of what we live is not articulated.