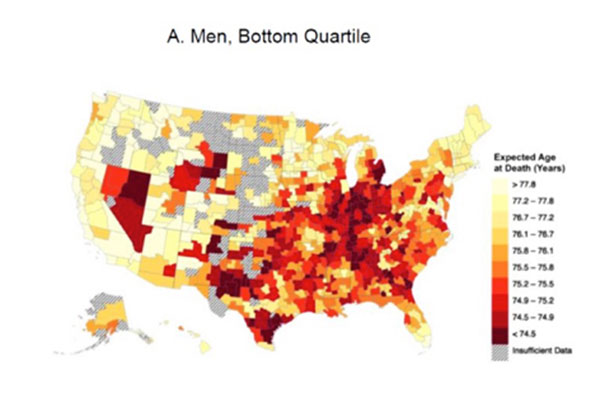

For low-income people, the darker colors on the bar and related map indicate the lowest life expectancy — fewer than 74.5 years. The lighter colors indicate a life expectancy of more than 77.8 years. Courtesy of David Cutler

Graphics courtesy of David Cutler

For life expectancy, money matters

‘You might expect two or three years of life differential … but 10 or 15 years … it’s an immense difference’

Being poor in the United States is so hazardous to your health, a new study shows, that the average life expectancy of the lowest-income classes in America is now equal to that in Sudan or Pakistan.

A Harvard analysis of 1.4 billion Internal Revenue Service records on income and life expectancy that showed staggering differences in life expectancy between the richest and poorest also found evidence that low-income residents in wealthy areas, such as New York City and San Francisco, have life expectancies significantly longer than those in poorer regions.

While those differences can be chalked up, in part, to healthy behaviors — low-income residents in New York City smoke and drink less, exercise more, and have lower rates of obesity than the poor in other cities — it’s unclear what other factors might contribute to the difference, said David Cutler, the Otto Eckstein Professor of Applied Economics and a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“It’s not an overwhelming correlation with medical care or insurance coverage,” he said. “It’s not that the labor market is getting better — it’s not correlated with unemployment, or the expansion or contraction of the labor force, or how socially connected people feel. The only thing it seems to be correlated with is how educated and affluent the area is, so low-income people live longer in New York or San Francisco, and they live shorter in the industrial Midwest.”

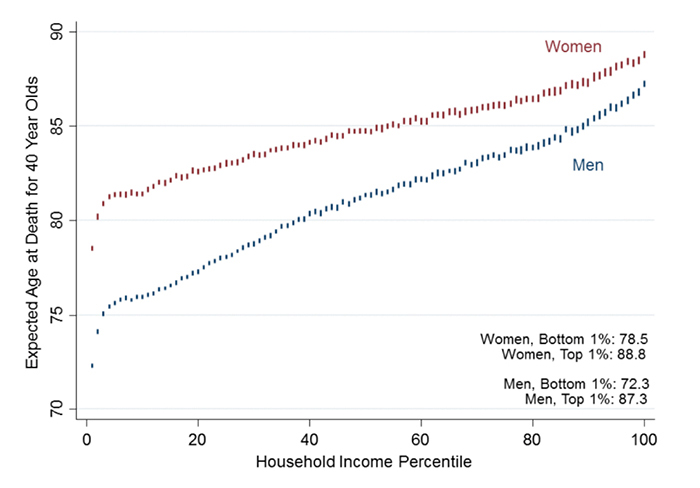

Among men, that gap is 15 years, roughly equivalent to the life expectancy difference between the United States and Sudan. For women, the 10-year difference between richest and poorest is equivalent to the health effects from a lifetime of smoking. The study is described in a paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association online on April 11.

“This paper really has two missions,” said Cutler. “One is to present this data, but the other is to create this data set so it can then be used by policymakers and researchers everywhere. This data has never been looked at with this level of granularity before.

“Previously, we could say what life expectancy was like in Massachusetts as compared to Michigan, but the problem is that Massachusetts is much richer than Michigan, and we know mortality varies with income,” he continued. “What we wanted to do was compare the same people in both cities — a shopkeeper in Detroit with a shopkeeper in Boston, not a biotech executive. That’s what we can do with this data that people haven’t been able to do previously.”

Cutler and his co-authors, including former Harvard Economics Professor Raj Chetty, now at Stanford University, collected federal tax records from 1999 through 2014, and sorted people into 100 percentiles according to income. By matching that income data with death records, the researchers were able to calculate the mortality rate and subsequent life expectancy at age 40 for each income level.

While researchers have long known that life expectancy increases with income, Cutler and others were surprised to find that trend never plateaued.

“There’s no income [above] which higher income is not associated with greater longevity, and there’s no income below which less income is not associated with lower survival,” he said. “It was already known that life expectancy increased with income, so we’re not the first to show that, but … everyone thought you had to hit a plateau at some point, or that it would plateau at the bottom, but that’s not the case.”

Cutler and Chetty then examined how life expectancy changed over time, and found that while life expectancy has increased for the wealthiest, it has edged up only slightly for low-income Americans.

“The increase has been approximately three years at the high end, versus zero for the lowest incomes,” Cutler said. “This is important, because it has major implications for Social Security policy. People say, ‘Americans are living longer, so we ought to delay the age of retirement,’ but … it’s a little bit unfair to say to low-income people that they’re going to get Social Security and Medicare for fewer years because investment bankers are living longer.”

When they laid the data over maps of the United States, Cutler and Chetty again found unexpected results, with low life expectancy concentrated not in the Deep South, but across the Midwest Rust Belt.

“What emerges strongly is that there is a belt from West Virginia, Kentucky, and down through parts of southern Ohio, through Oklahoma and into Texas — it’s not a story of the Deep South,” Cutler said. “The variability in where high-income people live longest is not as large and is much less geographically concentrated. You don’t see this same type of belt — it’s scattered all over.”

Going forward, Cutler, Chetty, and their co-authors have made the data publicly available in the hope it will spur further research into whether certain public policies or other economic indicators are associated with longer life expectancy. Cutler believes it also underscores some worrying truths about economic disparity in the United States.

“These differences are very, very troubling,” Cutler said. “The magnitude is startling. You might expect two or three years of life differential — which is roughly what we would get by curing cancer — but 10 or 15 years … it’s an immense difference. We don’t know exactly why or what to do about it, but now we have the tools to ask those questions.”

The research was supported by the U.S. Social Security Administration by a grant to the National Bureau of Economic Research as part of the SSA Retirement Research Consortium, the National Institutes of Health, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Smith Richardson Foundation, and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.