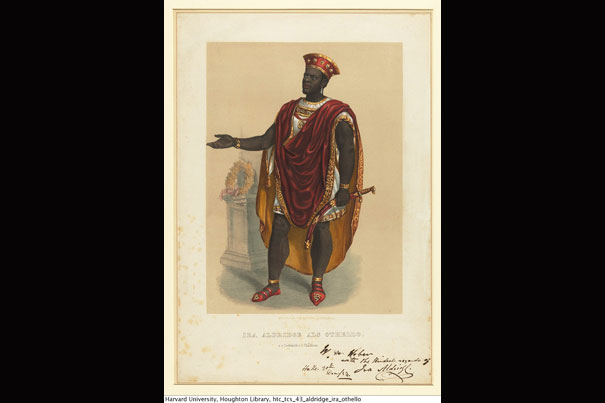

Ira Aldridge was the first black actor cast as Othello. Although he was extremely successful, it would take another century before another black man was cast in the role.

Image courtesy of Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library/Harvard University

Speaking up through Shakespeare

African-American voices give Houghton exhibit extra layer of complexity

Paul Robeson, the great 20th-century actor, commands the Edison and Newman Room at Houghton Library, in a life-size theater poster from “Othello,” one of dozens of artifacts in an exhibit marking the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

Robeson’s gaze is intense and unsettling, and reflects the “complex engagement black actors have had with Shakespeare,” says Dale Stinchcomb, curatorial assistant for the Harvard Theatre Collection at Houghton.

“While historically Shakespeare’s texts have been the province of white elites, they nonetheless speak convincingly to the experience of ‘others,’ as well as to concerns we tend to think of as modern: race, class, and gender,” Stinchcomb says. “‘Othello’ dwells so much on the social repercussions of blackness that it must have presented both an agonizing and an enticing role. This feeling of close and ambivalent identification is not unusual.”

In celebrating the Bard of Avon — April 23 is thought to be the date of both his birth and death — the Houghton exhibit also recognizes the art and activism black actors have brought to Shakespeare’s works.

“Robeson was one of the most recognizable African-Americans of his time internationally,” says Stinchcomb. “He must have had incredible courage to persevere. He was a very principled man, and his Othello possessed the same unstrained nobility.”

Robeson performed in “Othello” at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge in 1942. A year later he took the role to New York for a production that still stands as the longest-running Shakespeare play on Broadway — 296 performances before a national tour. Robeson called the shots, Stinchcomb says, insisting on performing only for integrated audiences. “He was an uncompromising activist.”

Matthew Wittmann, curator of the Harvard Theatre Collection, said that the work of African-American performers like those featured in the exhibit shows how “malleable” the Shakespeare canon is.

James Hewlett was the first black actor to perform professionally on the American stage when he played the lead in a production of “Richard III” in 1821. He was part of the African Grove Theatre, which put on Shakespeare plays to segregated audiences. Paul Robeson played the lead in a 1942 production of Othello (that premiered at the Brattle Theater the same year) was so successful that it set a record of 296 performances on Broadway and a national tour. He would only perform to desegregated audiences, which basically stopped them from performing in the South.

Images courtesy of Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library/Harvard University

“Shakespeare has meant something very different to people in various times and places. … Each [African-American actor] struggled in their own way with both the texts and the racism that surrounded their appearances on stage,” Wittmann says. “The prejudice Paul Robeson faced amidst the landmark Broadway production of ‘Othello’ showed the persistent and pernicious influence that racism had on the American stage. Still, the pioneering efforts of James Hewlett and the African-American actors that followed used Shakespeare to transcend the circumstances that sought to limit their artistry because of their race.”

The exhibit includes a letter to John Haggott, the producer of the 1943 “Othello” and a 1935 Harvard grad, from the chairman of Baylor University’s English Department, Andrew Joseph Armstrong. The academic wrote: “It would not work at all for the whites and negroes to sit together. That would not be allowed in Texas where the Jim Crow laws are enforced quite definitely.”

Haggott’s reply came within a week: “‘There shall be no segregation, grouping or setting apart of audiences because of race, creed or color,’” he wrote, quoting the theater’s contract.

The rare objects of “Shakespeare: His Collected Works” include an 1854 lithograph of Ira Aldridge, the first black actor cast as Othello, and an 1820 engraving of James Hewlett, whose Richard III in the all-black African Grove Theatre made him the first black actor to perform the role on an American stage. There is also a sketch by costume designer Robert Fletcher, Harvard Class of ’45, who dressed James Earl Jones for a 1981 performance of “Othello.”

Said Jones: “I have always taken ‘Othello’ personally — perhaps too personally — and I am not alone.”

“Shakespeare: His Collected Works” runs through April 30.