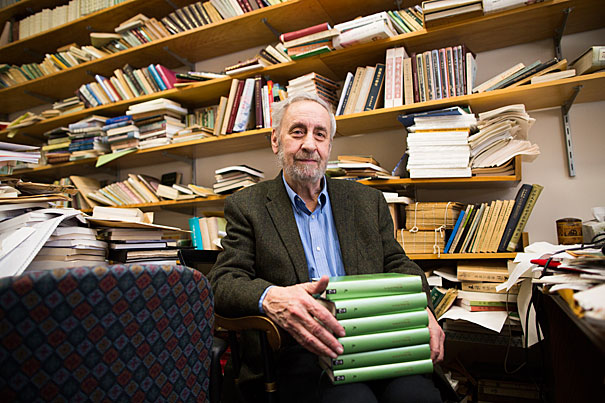

Harvard Professor Stephen Owen spent eight years translating the complete works of Chinese poet Du Fu. “I didn’t believe it until I held it in my hand,” he admitted. The finished volumes weigh nine pounds and comprise 3,000 pages.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Translating nine pounds of poetry

Sinologist Stephen Owen publishes first complete English translation of Chinese poet Du Fu

Stephen Owen doesn’t understate the intellectual stamina required to maintain a healthy relationship with the Chinese poet Du Fu.

“If you’ve got to be stuck with someone for eight years, you want it to be someone you enjoy, who can sustain your interest,” said the James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard, who recently published “The Poetry of Du Fu,” the first complete English translation of the great Tang dynasty literary figure.

A monumental undertaking (the prolific Du Fu left 1,400 extant poems), Owen spent nearly a decade working on the translation, which resulted in a 3,000-page, six-volume book that weighs in at nine pounds.

“I didn’t believe it until I held it in my hand,” he said. “There’s something to having the physical copy.”

Owen, a sinologist who has written extensively about Chinese literature, counts “The Poetry of Du Fu” as his 13th published effort, and he expects the substantive book, which is free to download but retails as a hard copy for $210, to find its way into academic libraries and the homes of Chinese-American parents who want their children to grow up familiar with some of the work of the poet, who is considered “the Shakespeare of China.”

“This is for general readers and scholars, but mostly for those who know some Chinese, but not enough to read Du Fu. This is to help them,” said Owen.

Poetry and commitment

Professor Stephen Owen reads from “The Poetry of Du Fu,” the first complete English translation of the Chinese poet, which took eight years to complete.

Like the Bard of Avon, Du Fu’s writing is layered and shows immense range. The elusive poet wrote in a wide variety of styles and registers. Inside the green-bound volumes are acclaimed verses such as “Moonlit Night” and “View in Spring,” but Owen argues that Du Fu “is a lot more fun when you get out of the well-known ones.” Sitting in his office with shelves and tables stuffed with books, he reflected on the poet’s habit of traveling — always accompanied by all of his poems and his personal library.

“He’s a quirky poet. When he moves to Chengdu with his family, he has to set up house and writes a poem to people asking for fruit trees and crockery. No one had ever done this kind of poem. He has a poem praising his bondservant Xinxing for repairing a water-piping system in his house. It’s a wonderful poem about the joy and discoveries of living in the real world instead of living in the rarefied poetic world,” Owen said.

Du Fu tackles the subject of war extensively, but there is also a poem about bean sauce and another about taking down a gourd trellis in which Du Fu compares the challenging, if mundane, task to the fall of the Shang dynasty.

“He’s forgotten what you can and can’t do in poetry, and 30 years later poets looked back and said, ‘This is the greatest poet we have,’” Owen said.

In its simplest form, Chinese poetry is not easy to translate. It doesn’t have tenses and rarely uses pronouns. There is no easy way to tell whether a noun is singular or plural. If the characters read: “bird fly sky,” Owen says, that can be interpreted as either “A bird flies in the sky” or “Birds fly in the sky.”

“You read the title — that’s the most important thing,” he said, adding, “Of course, it’s maddening.”

Frustrating moments aside, the project was a long-in-the-works dream, born of a 2005 Mellon Foundation Distinguished Achievement Award, which gave Owen $1.5 million to fund this and other projects. “The Complete Poetry of Du Fu” will inaugurate the Library of Chinese Humanities, an accessible series of pre-modern Chinese facing-page texts and translations published by De Gruyter. Owen expected the Du Fu translation to take three years, but teaching responsibilities and speaking engagements set him back numerous times.

“It owns you. I got teaching relief for a couple of semesters, and I worked on it and I worked on it. It wasn’t that I was lazy,” he said. “You see the territory that has to be done. You have to plow the south 40, and have plowed the south 28, and see what still has to be done.”

Owen, who is 69, worked primarily alone, allowing a graduate student to go over the work only after it was complete.

“Du Fu’s a great person to translate, but there goes eight years of your life. Finally it’s done,” he said.