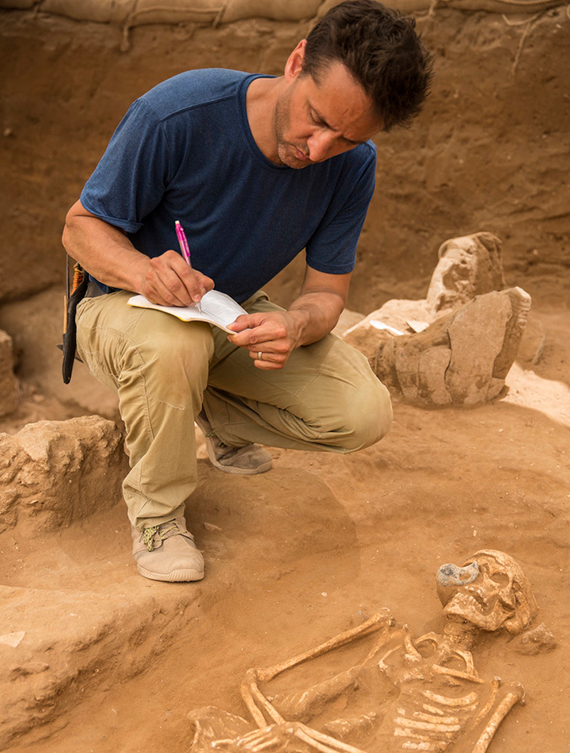

A skull from the excavation of the Philistine cemetery by the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon.

Photo © Tsafrir Abayov for the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon

Unearthed bones bring Philistines to life

Hard-earned breakthrough for Harvard-backed team

Hidden in the soil of Ashkelon, an Israeli seaport 35 miles south of Tel Aviv, are secrets from the ancient world that Harvard scholars have been uncovering for decades. Not very long ago, they struck a treasure trove of bones.

“It was just a goldmine of a cemetery,” said Daniel Master, an archaeology professor at Wheaton College in Illinois and a co-director of the Harvard-backed Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon, which carried out the first-ever excavation of a Philistine burial ground, found at the site in 2013. “Every kind of idea we would want was there.”

For years archaeologists have searched for the origins of the Philistines, famously known, via the Hebrew Bible, as the archenemy of ancient Israel. The cemetery both shines an important light on the group’s history and sets their ancient burial record straight.

“There have been pages and pages and pages of scholarship, so-called, talking about Philistine burial customs, and 99 percent of it is utter nonsense now that we really know how they were buried,” said Lawrence E. Stager, Harvard’s Dorot Professor of the Archaeology of Israel Emeritus and a co-director of the expedition. “We see that these burial patterns are very different from what we know of Canaanite culture, Egyptian culture, and Israelite culture. So we now have comparative and contrasting archaeology.”

The expedition, nearing its end after 31 years in the field, is sponsored by the Harvard Semitic Museum, Boston College, Wheaton College, and Troy University, and is licensed by the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority.

For the past three years, researchers have gently unearthed 160 individual remains: men, women, and a few young children, most buried in simple pits, some in stone-lined chambers, others cremated. Many of the dead were laid to rest on their backs along with personal items such as jewelry, weapons, or ceramics. A large number were “accompanied by two storage jars, one of which is often topped with a bowl, and then a little juglet on top,” said Master, adding that the role of the objects in burial remains a mystery.

It’s the bones themselves that may offer the best insights into the lives and ancestry of the Philistines. Researchers will use DNA, radiocarbon, and biological distance testing in the coming months and years to help determine the Philistines’ exact origin, looking to support the long-held view that they were “sea peoples” who migrated to the area from the West around the 12th century B.C. Careful examinations of the remains will also help scholars paint an accurate picture of how the Philistines actually looked, how tall they were, how healthy they were, and even how long they lived.

“We are getting a sense of people who suffered malnutrition at youth and we see that in their teeth,” said Master. “We are getting a sense for some of the things that they experienced in their life, on a very personal level, their medical history, as it were, that we can’t get from looking at the houses or the pottery or the bread ovens that they left behind.”

Thirty years of work

Since 1985 the Leon Levy Expedition has carefully excavated the 150-acre site nestled inside a national park on the edge of Mediterranean. The ancient seaport, whose history spans from the Bronze Age through the Crusades, has yielded vivid clues to the lives of its past inhabitants: Canaanites, Israelites, Philistines, Babylonians, Phoenicians, Mycenaeans, Greeks, and Romans. Findings have included pottery, coins, jewelry, and statues, as well as various examples of advanced architecture, such as the oldest known arched gateway, dating to 1800 B.C.

Discoveries at the site point to both the beginning and the end of Philistine civilization at Ashkelon, and, contrary to lore, their level of sophistication. Elite Philistine houses dating from the 12th-10th centuries B.C. have been uncovered, along with a “snapshot” of the city’s once-bustling marketplace, frozen in time when the armies of the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II set Ashkelon ablaze in 604 B.C.

“It’s a bit of a Pompeii moment,” said Master of the marketplace, which was discovered in 1992. The remains of wine and grain shops along a busy thoroughfare, as well as ancient receipts from the buying and selling of those goods, shed light on the Philistines’ thriving economy.

“We’ve got the beginning and we’ve got the end and both of these things have been profound contributions to the study of the Philistines,” said Master. “But here we are seeing the people themselves, and we are going to learn things that we can learn only from the bones.”

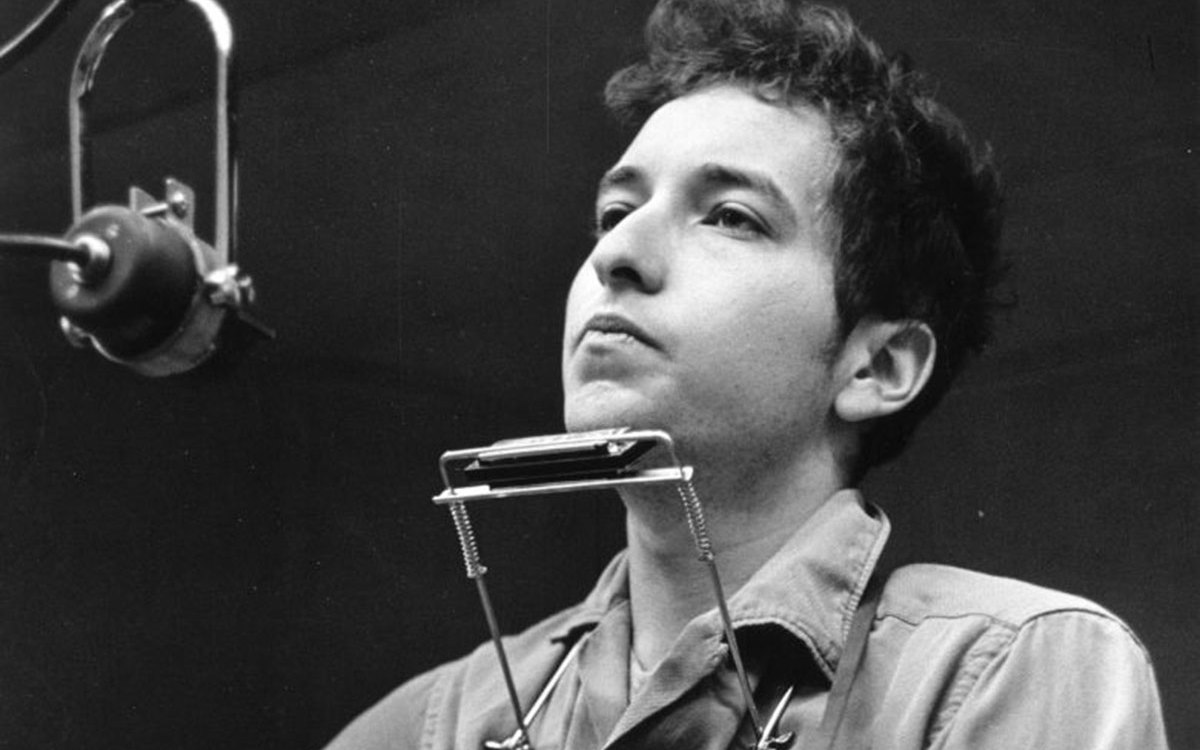

Facing the past

Coming face-to-face with the Philistines has been a highlight for Harvard’s Adam Aja, the man largely responsible for the close encounter.

On a summer night near the end of the 2013 season, Aja, an assistant director of the expedition and an assistant curator at the Harvard Semitic Museum, was hot, tired, and covered in dust. The light would soon be gone. But he had a hunch: “Keep digging.”

‘This is the personal connection that I have always been looking for, this personal connection with the people whose story I have been trying to tell.’ — Adam Aja

Recently he had met with a retired worker from the Israel Antiquities Authority who claimed that almost two decades prior he had uncovered human remains near the city’s northern edge, roughly 60 centimeters from the surface. The day before members of the expedition had scoured the area the man had described, an unexplored corner of land outside the ancient city’s walls. They dug one hole after another. Each time the result was the same: nothing.

Aja had returned for one last try accompanied only by an Israeli worker manning a backhoe. The results were so far the same.

“Absolutely nothing,” recalled Aja. “It was just empty soil.”

With about 30 minutes left in their day, Aja asked the driver to dig as far down as the machine’s arm would go, farther than they had dug before based on their source’s recollection. When the bucket came back up, Aja sifted through the haul, finding a bone. Years of experience told him “this was not an animal bone.”

Aja scrambled into the bucket and was lowered into the pit, where he quickly unearthed more bones and a human tooth. Two weeks later, Aja, Master, and the remaining staff at the site widened the hole and kept digging. “It was a crazy two days,” said Aja. “The evidence just kept coming. We knew we had something significant at that point. We had pottery, we had full articulated remains.”

Above all, Aja had his direct connection to the people he had sought for so long. Finding the occasional earring lying in the street, or a bead mixed in with ruins, paled in comparison, Aja said, to finding such items on the remains of actual Philistines.

“To see how they wore the earrings up the ear, high and low. Full beaded necklaces … carnelian followed by a shell, followed by copper,” said Aja. “This is the personal connection that I have always been looking for, this personal connection with the people whose story I have been trying to tell.”

The work pace is unrelenting at the site, which for summers through the decades has doubled as an outdoor classroom for both students and volunteers.

A daily wakeup call comes at 4:30 a.m., followed by a quick breakfast. Prep work at the site begins before dawn and digging lasts until around 1, followed by lunch and field school classes. Staff members and volunteers are back at the site from 4 to 6 p.m. processing the day’s finds. Many staffers spend additional hours at night washing, photographing, and documenting artifacts. It often adds up to 12-hour days, often in brutal heat. But the effort has yielded huge rewards, said Aja, who has put in “a lot of double shifts” in recent seasons to help the expedition wind down.

“If we don’t do it, no one is going to,” said Aja, whose drive to keep digging led to one of the greatest Philistine finds in history. “This is the one shot in the world to see this stuff.”