Worlds of promise

For students, educators, physicians, and X-wing lovers, future of virtual reality dazzles

More like this

The people wearing the giant goggles and laughing, ducking, jumping, and wildly waving their arms weren’t the only ones having fun.

“Watching people in visual reality is the best thing,” said a man as he waited for a chance to don a large black headset and hand-held controllers and take a turn as a professional hockey goalie deflecting virtual pucks.

“Dude, it’s addicting,” said another, fresh from a trip to the ocean floor and a close encounter with a blue whale. Across the hall, a line formed for a motion simulator that mimicked a shaking race car, taking headset-wearing users for a spin on a virtual speedway.

For a real-world observer at the Harvard Innovation Lab (i-lab) on Wednesday, the entertainment potential of visual and augmented reality was abundantly clear.

But what many consider the next great tech revolution isn’t only about fun. Experts say it has the potential to transform business, art, education, science, design, manufacturing, and medicine. It’s also expected to be worth $100 billion by 2020.

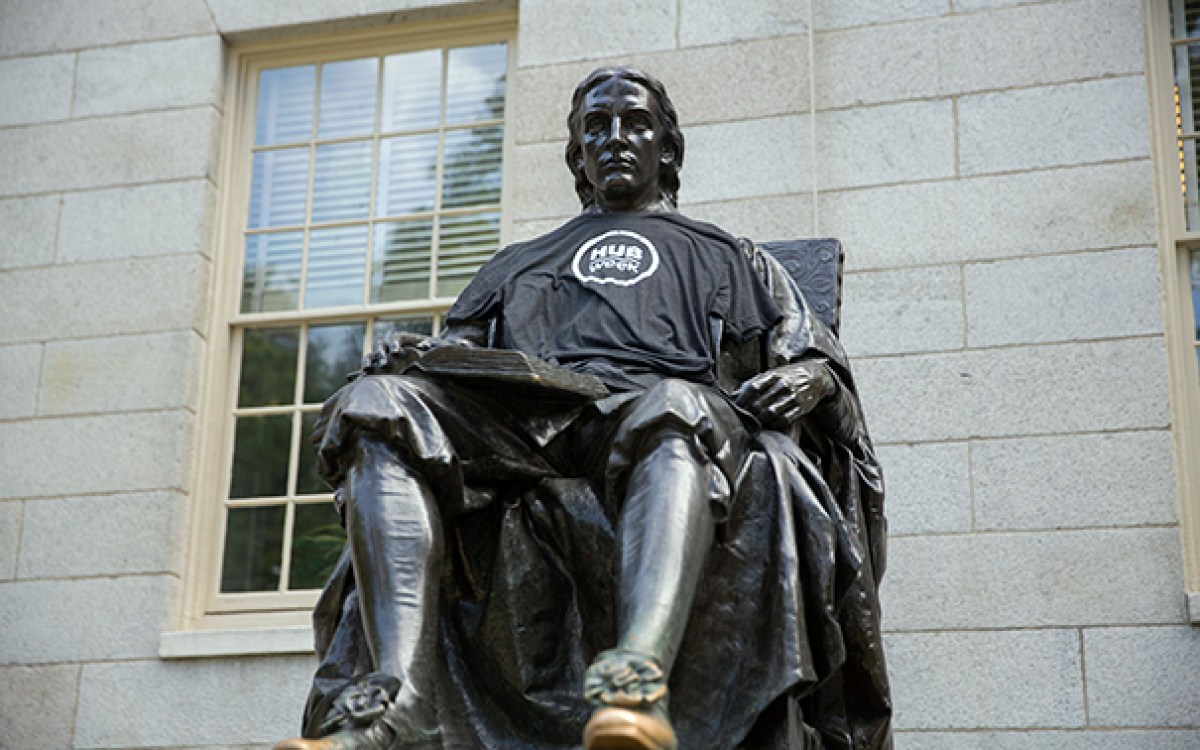

The future of virtual and augmented reality was the theme of a HUBweek event that attracted scholars, students, scientists, educators, entrepreneurs, and software developers along with the merely curious for an afternoon of demonstrations and discussions.

In the coming weeks the i-lab will open its own augmented reality-virtual reality lab, said Jodi Goldstein, the facility’s Bruce and Bridgitt Evans Managing Director. Goldstein introduced the keynote address, featuring Rony Abovitz video-linked to the talk via a rolling robot. Abovitz, an entrepreneur who made his mark with computer-assisted surgery, is the man behind what Goldstein called “one of the most mysterious yet highly transformative ventures in this space”: Magic Leap Inc.

Abovitz’s firm is developing “Mixed Reality Lightfield,” a combination of virtual reality, in which users wear goggles and look into a screen that simulates an alternate universe; augmented reality, which takes a person’s view of the real world and layers on top of it things such as Pokémon characters or maps of the nearest subway stops; and light fields.

The technology fits perfectly with the brain’s spatially oriented visual-processing mechanism, said Abovitz, and will open a world of discovery to those who have struggled to transfer two-dimensional information or text into “spatial learning.”

“I think it will make life easier for a lot of people and open doors for a lot of people because we are making technology fit how our brains evolved into the physics of the universe rather than forcing our brains to adapt to a more limited technology,” said the Magic Leap president and CEO, whose hopes for the technology include, among other things, parking a virtual “Star Wars” X-wing in his driveway.

A range of discussions highlighted the practical applications of virtual reality. In a session on surgery and rehabilitation, Jayender Jagadeesan, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, described research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in which a modified Oculus Rift augmented-reality headset is helping surgeons determine a tumor’s exact location.

“You can pull in any of the patient’s specific imaging, while the surgeon is actually doing this procedure,” Jagadeesan said of the multiple diagnostic screens a physician can instantly access while wearing the headset during an operation.

Chris Dede of the Harvard Graduate School of Education discussed his work on a suite of virtual and augmented reality applications for young learners.

“You can be in a classroom in the middle of the winter, but psychologically you are at a pond or a forest in the middle of the summer,” said Dede, the Timothy E. Wirth Professor in Learning Technologies, of ecoMUVE, a technology that uses immersive virtual environments to teach students about delicate ecosystems.

In the i-lab’s exhibit hall visitors had access to a range of experiences and applications, including a round rolling camera developed to help first responders assess dangerous situations and a wearable device that lets users feel virtual objects.

Among the Harvard undergrads at the event was Madeleine Woods ’19, who was on site with Harvard College Virtual Reality, or Convrgency. The organization aims to bring students together to explore the creative potential of virtual reality.

Woods, a joint concentrator in folklore and mythology and English with a secondary in archaeology, described herself as a theater kid who loves the arts and humanities along with coding and technology. She said virtual reality merges her varied interests, calling it both “empathetic” and “humanistic.”

“This is the first time I think technology really opens people up,” said Woods. “You can experience the life of someone else across the world. You can see something you’ve never [seen in person]. I think you can understand people so much better when you can walk in their shoes, and this is something that literally puts that technology in hand.”