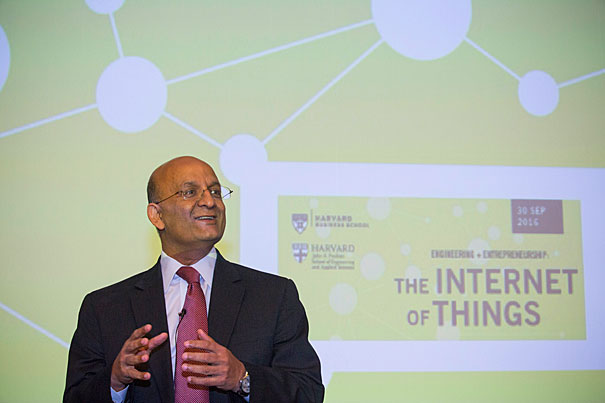

A keynote talk is given by Brenna Berman, Chicago Department of Innovation and Technology CIO during “Engineering and Entrepreneurship: The Internet of Things,” in which everyday objects possess network connectivity that allows them to send and receive data, radically transforming the way we live and work.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Now arriving: Internet of Things

HUBweek session examines the rise of smart devices, and the accompanying loss of privacy

While several technical experts highlighted just how smart our appliances, lights, cars, factories, and even cities are becoming, another questioned whether we’re thinking hard enough about what technology should do rather than what it can do.

As computers get smarter, smaller, and more portable, their brains are being added to an array of formerly dumb devices in all aspects of our lives, even when we are on the road. These smart devices are increasingly equipped with sensors and connected to the internet, allowing data to flow from the external environment to central collection points to be stored, analyzed, and used for a variety of purposes, including optimizing performance.

But the massive amount of data being gathered also raises ethical questions about its use, and Jim Waldo, Gordon McKay Professor of the Practice of Computer Science and chief technology officer at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, said those questions increasingly are being answered not by philosophers, ethicists, regulators, or legislators, but by programmers designing the software that guides the devices’ behavior.

“What we are doing is instrumenting the world at a greater and greater density to get more and more data to do interesting things,” Waldo said. “[It’s] opening up not just very interesting uses, but very troubling abuses.”

The growing sophistication of the global Internet of Things was the focus of a HUBweek event Friday at Harvard’s Northwest Building. Speakers highlighted specific projects, including the city of Chicago’s experimental sensor network gathering several kinds of data, drones used for environmental research, smart lighting that could cut electric bills by 90 percent, the potential of a future smart energy grid to handle the variability of clean energy, and the importance of machine learning to the continued growth of the Internet of Things.

Harvard Business School Dean Nitin Nohria and Harvard Paulson School Dean Frank Doyle offered introductory remarks at the event, with Nohria saying that the Internet of Things has the potential to have an enormous impact both at home and in the business world.

“It’s not just an opportunity for the world, but an opportunity in which Boston can yet again be a pioneer,” Nohria said.

Other speakers included Brenna Berman, Chicago’s chief information officer; Rajiv Lal, the Stanley Roth Sr. Professor of Retailing, who led a case discussion of a smart-lighting company; Scot Martin, the Gordon McKay Professor of Environmental Chemistry; Na Li, assistant professor of electrical engineering and applied mathematics; and David Brooks, the Gordon McKay Professor of Computer Science. The session was hosted by Lal and Herchel Smith Professor of Computer Science Margo Seltzer.

The event was sponsored by the Center for Research on Computation and Society, the Institute for Applied Computational Science, both at the Harvard Paulson School, and by Harvard Business School.

Berman discussed several initiatives underway in Chicago, including one that uses consumer complaints to direct more effectively an undermanned crew of health inspectors. The work, currently in a pilot phase, crunches 34 variables to target the restaurants likeliest to have unsanitary conditions and reaches them an average of 7.4 days earlier than under existing protocols. The aim, Berman said, is to reduce cases of food poisoning in the city.

The city is using a similar model, Berman said, to guide its rodent-baiting program to head off outbreaks, and to target illegal cigarette sales. The city is committed, Berman said, to data-informed decision-making. Chicago has deployed 28 sensor arrays — and plans 500 by the end of 2018 — that monitor temperature, humidity, sound, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, pollen, and diesel, and that also have cameras to gather information on pedestrian, bicycle, and vehicle interactions. One initial priority for the gathered data is to examine pedestrian and vehicle near-misses.

In his discussion of ethics, Waldo, who has a doctorate in philosophy and teaches a course on cyber-privacy, said security concerns are sometimes raised when images and sensor data are gathered in public places, but programmers regularly make what are tantamount to ethical decisions in an array of fields. Those decisions, he said, will have a far larger sway in how devices operate and how data is used than any belated regulatory decisions made by politicians.

“Policymakers are somewhere between three and 20 years behind what we’re doing,” Waldo said. “By the time policy is discussed, we’re on the third generation, and the reality on the ground overrides policy.”

Another speaker offered a scenario of smart service that the Internet of Things could enable. A home repair to a furnace or appliance could be scheduled just before a device breaks rather than just after, with the repair company acting on information sent from the device itself. The repairman could automatically be scheduled when you’re home because your smart devices know you have an extra cup of coffee on Saturday mornings and so are likely to be there. But would the system be as benign, Waldo asked, when you’d had your third glass of wine and the data went to your doctor and insurance agent?

Similar ethical issues are playing out in the real world, Waldo said. The complex software guiding self-driving cars has life-and-death consequences, and in designing them programmers are making critical decisions that could affect people’s lives. If that work is done without considering its ethical implications, that’s a grave mistake, he said.

“The Internet of Things might be a way to drive efficiency … It’s also the deployment of the most sophisticated surveillance state there has ever been,” Waldo said. “As you design these things, you are making policy decisions. You need to engage with people who think about these things, if you don’t.”