Birth of a peaceful Europe

70 years ago, a little-heralded speech at Harvard’s Commencement outlined the Marshall Plan, which calmed a continent

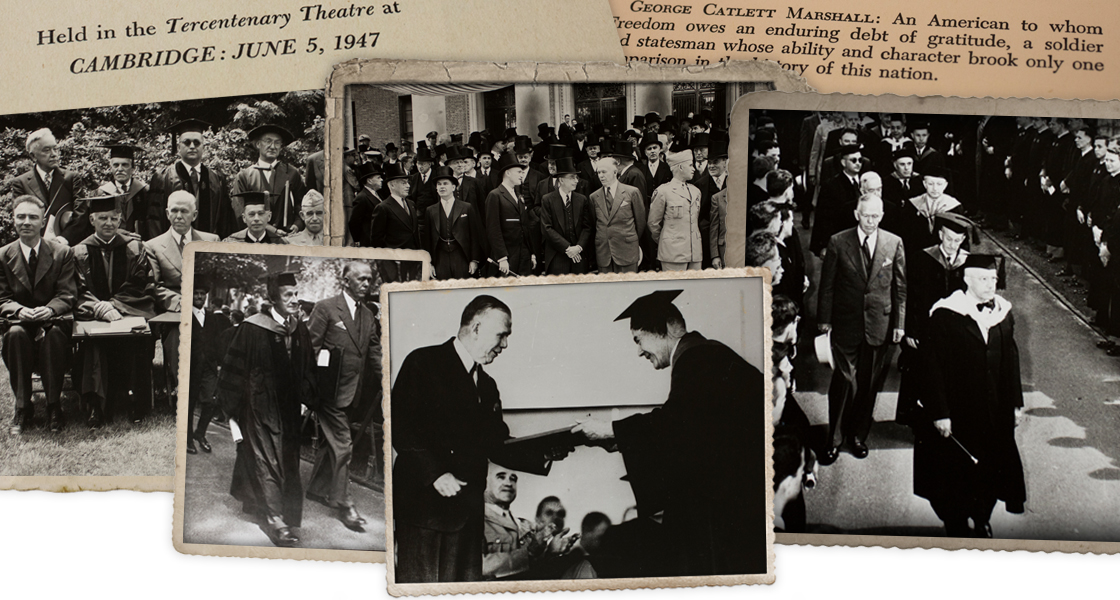

Seventy years ago, on June 5, 1947, U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall delivered a short, unadorned Commencement speech that seemed unremarkable to most listeners at the time. Yet it changed the world.

The retired five-star general, credited during World War II with organizing the fastest and biggest military buildup in U.S. history, took just under 11 minutes to announce the creation of one of the largest international economic aid programs in history. Over the next four years, the United States delivered nearly $13 billion (in today’s dollars, $122 billion) in assistance to participating European nations under the European Recovery Program, soon known as the Marshall Plan.

Those actions stabilized a continent riven by two world wars and exhausted by them. The Marshall Plan’s assistance benefited more than a dozen nations, steadied their economies, encouraged their cooperation, stemmed the spread of communism, and helped create the European Union that led to decades of prosperity and ended the continent’s ruinous cycle of warfare.

At 1947 Harvard Commencement, George Marshall announces Marshall Plan

Marshall, who had been invited to receive an honorary degree at Harvard’s 296th Commencement exercises, recounted in his speech how, two years after the end of World War II, the devastated European economies were continuing to struggle, and hunger was ravaging the land.

Left unspoken was a fear he shared with President Harry Truman that continued economic turmoil would lead to political chaos, shatter European democratic rule, and foster the growth of Soviet-backed communist parties across Western Europe.

Outlining the postwar challenge

Avoiding soaring rhetoric, the pragmatic Marshall outlined the postwar challenge this way: “Europe’s requirements for the next three or four years of foreign food and other essential products — principally from America — are so much greater than her present ability to pay that she must have substantial additional help.” Without such support, he said, Europe would “face economic, social, and political deterioration of a very grave character.”

It was only logical, he said, that the United States do what it could to restore “normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.”

Few in the audience appreciated the importance of these remarks at the time, even, by his own account, Harvard President James B. Conant. The two men had exchanged a series of letters in which Marshall indicated his limited plans for his remarks. “As I wrote to you on May 9th, I will not be able to make a formal address, but would be pleased to make a few remarks in appreciation of the honor,” Marshall said in a typewritten letter to Conant dated May 28, 1947, “and perhaps a little more.”

“It was a serious, thoughtful, well-reasoned speech, but it wasn’t a kind of speech you would expect these days from a leader who is proposing a historic initiative,” said Tom O’Donnell, a member of the Class of 1947 who had secured an advance copy of the speech from friends in the Harvard News Office. He didn’t immediately see its significance. “It wasn’t full of numbers … it was really quite prosaic.

“People were delighted to see Marshall. He was universally revered and very popular,” he added. “But I don’t think people expected a historic message — and we got one.”

Expectations for Marshall’s visit had been so modest, in fact, that the more heralded speaker that day was another retired five-star general, Omar N. Bradley. He had commanded American ground forces in Europe during the drive east into Nazi Germany, and in 1947 was head of the Veterans Administration.

Still, Marshall was the perfect messenger for such a forward-looking, if unexpected, speech. The veteran soldier and statesman was a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute who during World War I had been on the staff of commanding Gen. John J. Pershing. By World War II, Marshall was Army chief of staff and mastermind of the U.S. military buildup. He also was a key architect of Operation Overlord, the massive allied invasion of France in 1944 that was a key turning point in the war. Truman appointed him secretary of state in 1947.

According to the Harvard News Office, 2,185 students received their degrees on that June 5. The afternoon was sunny and mild. Earlier in the week, storms had chased Commencement’s traditional senior spread on June 3, an evening of dinner and dancing originally set for the Lowell House triangle, indoors.

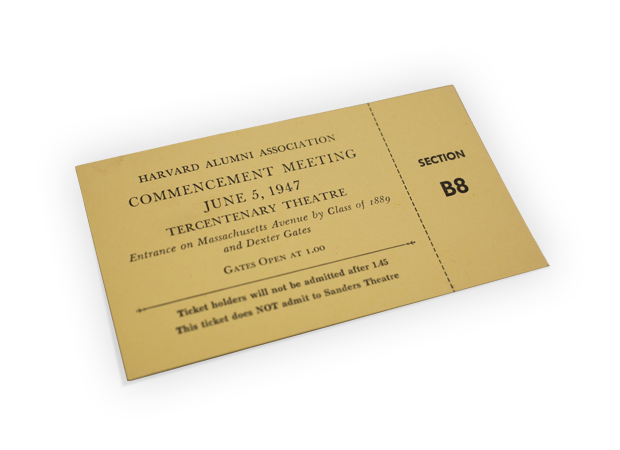

Harvard Yard’s Tercentenary Theatre filled with 15,000 people for the first normal Commencement since the war. The conflict had not only depleted the number of Harvard undergraduates still on campus, but condensed the annual week of graduation festivities into a day.

The war years also had ushered in co-ed classes on campus. Beginning in 1943, women from Radcliffe were allowed to take courses with Harvard men. “I have to say, I never knew anyone who found it objectionable. We all thought it was great,” said O’Donnell.

The Harvard Band played as dignitaries and officials processed to the makeshift stage, which was covered by a gray and red canvas canopy. Many participants wore morning suits and top hats. Tall and lean, Marshall wore a double-breasted, gray sharkskin suit and a blue tie. The tip of a neatly folded blue handkerchief peeked out of his breast pocket.

The honorands who took the stage with Marshall and Bradley for the day’s Morning Exercises including an archaeologist, a naval architect, a marine engineer, a typographical designer, and a poet, T.S. Eliot. Marshall, the man who became the face of peaceful European reconstruction, was seated near another honoree, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, whose work was pivotal to developing the first atomic bomb.

“People were delighted to see Marshall. He was universally revered and very popular. But I don’t think people expected a historic message — and we got one.”

— Tom O’Donnell ’47

A member of the Class of 1947, Bill Tyler, had been an infantryman in the war and had fought in Germany with the combat engineers, special units trained to “blow down bridges and blow holes in highways.” He had survived the Battle of the Bulge, the largest fought in Western Europe and the biggest battle ever fought by the U.S. Army.

To this day, he credits the controversial bomb that Oppenheimer helped to develop with saving his life. When dropped twice on Japan, it killed more than 100,000 people, yet it also prompted Japan to surrender, likely saving the lives of many thousands of allied troops. “I knew there was going to have to be a bloody landing on the Japanese islands,” said Tyler, “and that they would take me out of central Germany … and put me in that unit that would land on the beach, and that we probably, a lot of us, would lose our lives. So I say the atom bomb saved me.”

During the war, O’Donnell was enrolled in the Navy’s college officers’ V-12 training program. He was on campus for six terms, the equivalent of three years of courses under a compressed wartime schedule. The war ended in August 1945 with Japan’s surrender, just a few months before his official commissioning. Other students, he recalled, weren’t so lucky.

Five registered members of the Class of 1947 died in the war. “They all died in Europe, and none of them had reached the age of 20,” said O’Donnell, who had graduated in 1946 but kept his Class of 1947 affiliation. That June, he was living on campus as a proctor in Straus Hall and attending Harvard Law School.

“I didn’t know them. They were people who came very briefly, and then suddenly they were gone.”

Setting the stage for reconstruction

Marshall’s speech and the plan that bears his name became the capstone of American and British efforts to reorient postwar foreign policy to contend with the Soviet Union, a wartime ally turned adversary.

“Marshall was acutely aware that this was a plan to stabilize Western Europe politically because the administration was worried about the impact of communism, especially on labor unions,” said Charles S. Maier, Harvard’s Leverett Saltonstall Professor of History and co-editor of “The Marshall Plan and Germany: West German Development within the Framework of the European Recovery Program.”

“In effect, it was a plan designed to keep Western Europe safely in the liberal Western camp.”

Maier praised Marshall’s early decision to include the Soviet Union in the proposed aid package, a move that, when Soviet leader Joseph Stalin rejected it, ultimately buttressed U.S. claims of Soviet designs on the West. “The plan was extended to communist countries if they wanted to accept it,” Maier said. “They found the conditions unacceptable, as we knew they probably would. It’s just a multilayered and intelligent use of foreign economic policy.”

In addition to the Marshall Plan’s effectiveness in normalizing Western economies, historians now see it as an example of shrewd statecraft in its approach to both the Soviet Union and Germany. Instead of turning its back on Germany, the vanquished foe whose humiliation after World War I had contributed to the rise of Nazism, the United States extended a hand in support. Marshall and Truman recognized that a stable Germany could serve as a bulwark for democracy and economic liberalism in the heart of Europe.

“Without a stable democratic Germany in the center of Europe, it would have been much more difficult to create the European Union and a prosperous Europe that we have today,” said Joseph Nye Jr., Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor.

With the Marshall Plan, economic growth rates across Western Europe jumped, food rationing was slowly curtailed, every participating nation remained democratic, and West Germany re-emerged not only as a major economic power, but a democratic one. The plan also led to creation of trans-European organizations such as the Organisation for European Economic Co-Operation (OEEC) and the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). In turn, such groups set the stage for the foundation of the European Union and a Europe-wide currency.

An era of international engagement

For the United States, the plan also represented a historic, long-term shift in foreign policy, ushering in an era of international engagement following a history of isolationism. Nye sees the plan’s diplomatic foresight as its most enduring legacy, and an important lesson for today’s American policymakers, many of whom want the nation to shrink from international involvement.

“The United States has to stay engaged with the rest of the world to produce what you might call global public goods,” Nye said. “And if we don’t, nobody else will. In the 1930s we didn’t, and the result was disaster.” The plan helped create “a liberal international order that lasted for 70 years.”

“We should continue to stay involved and maintain our alliances,” he added, “and maintain the multilateral institutions which were the bedrock of that 70-year period.”

Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger agrees. Reflecting on the Marshall Plan in a 2015 essay for the Harvard Gazette, he called Marshall’s address “a clarion call to a permanent role for America in the construction of international order.”

“Marshall put an end to isolationist nostalgia,” with his speech, Kissinger said. “Declaring war on ‘desperation and chaos,’ he invited the United States to take long-term responsibility for both restoring Western Europe and recreating a global order.”

Archival material courtesy of Harvard University Archives.