A hand-carved effigy pipe of a flying man dressed in a sailor’s uniform, with an ornate pineapple design on his pants is one of the rarely seen treasures on exhibit. Gift of Frederick H. Rindge, Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Courtesy of Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

The world in an exhibit

As Peabody Museum turns 150, new exhibition highlights pioneering efforts and legacy of cultural history

For every remarkable object displayed in the new exhibition celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, visitors might be just as impressed by some other object they can’t so readily see.

There are more than 1.25 million items in the Peabody collections, only a choice sampling of which could fit into the display cases for the exhibition “All the World Is Here: Harvard’s Peabody Museum and the Invention of American Anthropology,” which opened in April. Alluring in another way, though, is the critical role the museum played in birthing a new social science.

“It’s tempting to say that Frederic Putnam, who served here as the second director of the museum from 1875 to 1909, almost single-handedly invented American anthropology as an academic field,” said Castle McLaughlin, curator of North American ethnography. “He started the anthropology department in 1890 and chaired it, and was responsible for designing anthropology exhibits at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, which led to the creation of the Field Museum of Natural History. He founded or co-founded dozens of publications and organizations. It’s amazing to realize all that he accomplished for museums and the field of anthropology.”

More than 250,000 people visit the Peabody every year, and millions more enjoy pieces loaned to other museums around the world.

“In some sense these collections belong to everyone,” said Jane Pickering, executive director of the Harvard Museums of Science & Culture. “We want everyone to experience and enjoy these collections through our exhibits and programs. This is one of the few places in the world where people can see such spectacular objects that represent the amazing diversity of human cultures.”

Walking into the restored fourth-floor gallery, visitors see first a sledge that Adm. Robert Peary used on his 1891-92 exploration of Greenland. Putnam helped to support Peary’s expedition and asked him to collect Inuit objects for display at the 1893 Chicago fair. Peabody conservation specialists have identified the five species used to make the vehicle as narwhal, walrus, whale, caribou, and seal.

“In the second half of the 19th century, Putman was a key figure in starting to codify theories and information about human prehistory. Then new technologies came along that enabled us to learn new things about our historic collections,” McLaughlin said.

Many objects in the exhibition, including some from Asia, Oceania, and the Americas, are rarely seen treasures, and can prompt a double take from visitors. There’s a hand-carved effigy pipe of a flying man dressed in a sailor’s uniform, with an ornate pineapple design on his pants; a “FeeJee Mermaid,” a skeletal fish-monkey artifact made in the 1800s from papier-mâché, wood, and fish skin; a model replica of Serpent Mound, an indigenous prehistoric site in Ohio that Putnam purchased to protect the archaeological remains; and a sailor’s cap from Lewis and Clark’s early 1800s expedition to the American Northwest.

“When most people think of anthropology, they think of curators going out and making systematic collections in distant, exotic places. But the earliest ethnographic collections in the Peabody were given by regional institutions such as the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Boston Athenaeum, where sea captains in the late-18th-century China trade deposited souvenirs they acquired from Native American trade partners on the Northwest Coast. Private patrons like Mary Hemenway played a huge role in supporting field research and donating collections, especially in the days before public funding existed,” said McLaughlin.

So closely tied are the museum and Harvard’s Department of Anthropology that Gary Urton, acting director of the museum and chair of the department, said many faculty still informally carry the title of curator.

“In the early days, the museum and the department were very closely connected. That close connection has existed for the history of the life of these two institutions, from the 1860s to the present day,” he said.

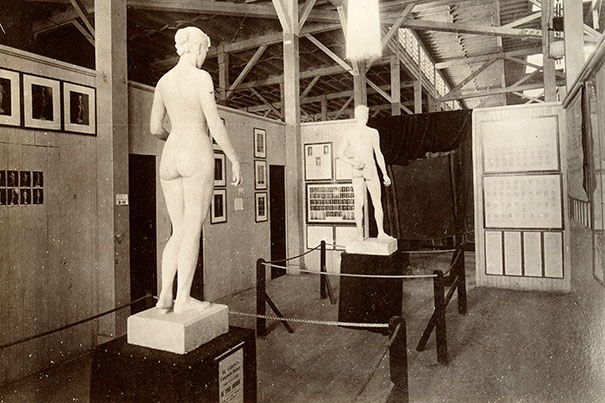

Arches in the gallery set off objects and ephemera from the Chicago World’s Fair. Curators Ilisa Barbash and Diana Loren displayed a pair of sculptures known as “the Typical Man and Woman,” cast according to measurements taken from thousands of people, including Harvard students, by the director of the Hemenway gymnasium in the 1890s.

“Some of the early research raises sensitive issues in today’s social and political climate. In addition, there was an inherent problem in the way collecting was done among what were then colonized or only recently decolonized societies. This exhibit provides the stimulus to think deeply and critically about such issues as earlier ideas of race and the conditions under which collections were formed. We don’t like to pretend these things didn’t happen,” said McLaughlin, who said the museum hosted a yearlong series of lectures titled “Race, Representation, and Museums” to address some of these topics in depth.

Rather than aggressively acquiring new objects, the museum now works with Native American tribes to return sacred objects to their ancestral homes and to incorporate native voices in interpreting and understanding the materials. Many faculty and museum curators collaborate closely with groups to help preserve their history and traditions in the museum and beyond.

William L. Fash, Bowditch Professor of Central American and Mexican Archaeology and Ethnology, and his wife, Barbara, director of the Peabody Museum’s Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Program, have worked in Copan, Honduras, for nearly 40 years, studying and preserving Maya ruins, and working with government staff and local students and teachers in cultural heritage work.

“We are standing on the shoulders of giants at the Peabody,” Fash said. “But now the countries and Native American communities we work in are deeply involved in historical archaeological inquiry. It’s actually fulfilling the original mission of the museum — archaeology and ethnology — in a conjoined way rather than in separate approaches. In some sense, the traditional roles are reversed in collaborative work of this sort because we scholars learn so much from the descendant populations, and we do our best to enhance their work in preserving traditional knowledge and practices.”

Where future engagement will lead the Peabody is the question for the next 150 years, said Urton, who believes the role and work of anthropologists will continue to evolve.

“Anthropology was initially interested in the colonized and the dispossessed. In this regard, the field wasn’t founded to study Western cultures; rather, its original focus was on non-Western societies. Now that we are all living in a global, transcultural world, these new circumstances cause us to rethink both the role of the museum and of anthropology in general,” he said. “We must ask: What is our role in the academy and in the world if our original subjects and their circumstances have changed so radically? Is it possible for anthropology and museums to remake themselves together? Or will there inevitably be a different path forward for each?”

The Peabody Museum is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. except for Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve and Day, and New Year’s Day.