To age better, eat better

Much of life is beyond our control, but dining smartly can help us live healthier, longer

Fifth in an occasional series on how Harvard researchers are tackling the problematic issues of aging.

A habitually healthy eater, Frank Hu stocks his refrigerator with fresh fruits and vegetables, fish, and chicken. His pantry holds brown rice, whole grains, and legumes, and his snack cabinet has nuts and seeds. He eats red meat only occasionally, rarely buys white bread, soda, bacon, or other processed meats. He’ll purchase chips and beer, but only now and then, mostly when entertaining friends.

When it comes to eating smartly in ways that can help us keep fit and live longer, Hu knows best.

“There is no single, fit-for-all diet for everyone,” said Frank Hu of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard University

Hu took over the Department of Nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in January. His eating habits are greatly informed by his research on what constitutes a healthy diet. While he knows they’re not for everyone, he says people can nonetheless move toward eating patterns that both appeal to them and help them stay well.

“There is no single, fit-for-all diet for everyone,” said Hu, a professor of nutrition and epidemiology and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “People should adopt healthy dietary patterns according to their food and cultural preferences and health conditions. I don’t have a rigid regimen, but I always emphasize healthy components in all my meals.”

And so, according to considerable research, can all those who want to reduce the risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and other chronic illnesses, and increase both longevity and quality of life in old age.

We become what we eat

To some extent, when it comes to healthy aging, we become what we eat. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one in four deaths results from heart disease, the leading cause of death in the United States. Among the top risk factors are obesity, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and poor diet — with the first three often tied to the last. The rise in obesity has hit the United States hard. More than a third of adults and one-fifth of children and adolescents age 2 to 19 are obese.

Research shows that sustained, thoughtful changes in diet can make the difference between health and illness, and sometimes between life and death. For more than 50 years, researchers who have studied the link between diet and health have extolled the virtues of the Mediterranean diet, with its emphasis on vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, olive oil, and fish, and its de-emphasis on red meat and dairy.

“The elements of a healthy diet were readily available in the Mediterranean, where people had to eat local fruits, vegetables, and fish.”

— Walter Willett

Pioneering studies, such as one led by nutrition expert Ancel Keys in the late 1950s, helped establish the Mediterranean diet as the benchmark. Keys’ landmark Seven Countries Study, which promoted diets low in saturated fats (beef, pork, butter, cream) and high in mono-unsaturated fats (avocados, olive oil), showed decidedly lower risks of cardiovascular disease.

Research by renowned Harvard nutritionist Walter Willett, who chaired the Nutrition Department for 25 years until this past January, has confirmed the pronounced benefits of the Mediterranean diet. In his 2000 book “Eat, Drink and Be Healthy,” Willett wrote that the “main elements of the Mediterranean lifestyle are connected with lower risks of many diseases.”

Using data from Harvard’s Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), a long-term epidemiological probe into women’s health, Willett also concluded that “heart diseases could be reduced by at least 80 percent by diet and lifestyle changes.”

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Nurses’ Health Study was established by Frank Speizer in 1976 to examine the long-term consequences of oral contraceptives. In 1989, Willett established NHS II to study diet and lifestyle risk factors. The results of that study have heavily influenced national dietary guidelines and the way Americans think about how they should eat.

Recent studies have found that a healthy diet can also boost the brain and slow cellular aging. Chef Dino Licudine greets seniors at the Center Communities at Hebrew SeniorLife, which is affiliated with Harvard Medical School. Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard University

“The picture that has emerged is that the traditional Mediterranean diet promotes health and well-being,” said Willett, the Fredrick John Stare Professor of Nutrition and Epidemiology. “The elements of a healthy diet were readily available in the Mediterranean, where people had to eat local fruits, vegetables, and fish. Back then, most people didn’t have much choice in what to eat.”

Researchers also generally approve of both the vegetarian diet and the Asian diet because they also help increase longevity and decrease the risk of chronic disease. But the Mediterranean reigns supreme, because the Asian diet has salt and starch, and the vegetarian lacks important nutrients.

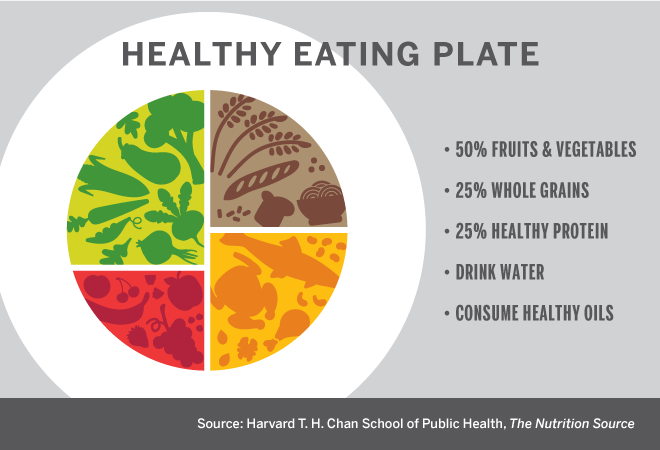

A design for healthy eating

To publicize everyday ways to eat better, researchers at the Harvard Chan School came up with the Healthy Eating Plate. It suggests eating more fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fish, lean poultry, and olive oil, and asks people to limit refined grains, trans fats, red meat, sugary drinks, and processed foods. In addition, it touts staying active.

Harvard’s plate was a response to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) MyPlate, which, a comparison by Harvard nutrition experts suggested, could have gone further in detailing information about which foods to favor or limit.

A 2012 Harvard study found that eating red meat led to increased cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality, and that substituting healthier proteins lowered mortality. As for milk, a source of calcium, Willett said there is no evidence that drinking more of it prevents bone fractures as much as physical activity does. Yogurt, because of its positive effects on the intestinal system, proves even more beneficial than milk.

“Most populations along the world don’t drink any milk as adults,” said Willett. “Interestingly enough, they have the lowest fractures. And the highest bone-fracture rates are in milk-drinking countries such as northern Europe and the United States. Calcium is important all through life, but the amount of calcium that we need is probably overstated.”

What is hard to overstate is the importance of eating healthily and mindfully through life, but the good news is that benefits begin as soon as the improved diet does. “If you’re still alive, it’s never too late to make a change in our diet,” said Willett.

Recent studies have found that a healthy diet can also boost the brain and slow cellular aging. Researchers are examining the role of coffee and berries in improving cognitive function and reducing the risks of neurodegenerative diseases. At the same time, researchers keep circling back to the Mediterranean diet as a model of healthy eating.

“The evidence is very encouraging because, even among old people, when they improve their diet quality, the risks of getting chronic diseases and mortality can be reduced, and longevity can be improved.”

— Frank Hu

In a 2015 study in Spain, seniors who ate a Mediterranean diet, supplemented with olive oil and nuts, showed improved cognitive function compared with a control group. Rich in antioxidants and polyphenols, chemicals that help avert the harm of “free radicals” in the body, the Mediterranean diet may even help prevent some degenerative diseases that, to some degree, are caused by vascular aging and chronic inflammation, Hu said.

“Healthy, plant-based foods can improve vascular health, not just in the heart but in the brain,” he said. “And that can slow down the aging of the brain and cellular aging, and reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.”

As of now, science says the best prescription to slow the effects of aging is a mix of factors, from regular exercising to a healthy diet to maintaining a healthy body weight. Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard University

Clues on biomarkers of aging

The research shows promising paths ahead. In a 2014 study, Hu found a correlation between the Mediterranean diet and telomere length, a biomarker of aging. Telomeres — caps at the end of chromosomes that protect them from deterioration — may hold a key to longevity. Their lengthening slows the effects of aging, and their shortening is linked to increased risks of cancer and decreased longevity.

As of now, science says the best prescription to slow the effects of aging is a mix of factors, from regular exercising to a healthy diet to maintaining a healthy body weight.

“Maintaining a healthy diet for a long period of time is more important than having a yo-yo diet,” said Hu. “The evidence is very encouraging because, even among old people, when they improve their diet quality, the risks of getting chronic diseases and mortality can be reduced, and longevity can be improved.”

Hu said his own diet is a fusion of the Mediterranean, Asian, and vegetarian models, and he tries to combine the healthiest elements of each. In general, he avoids the problematic components of the Western diet: sugary foods, processed meats with high amounts of preservatives, sodium, and saturated fats.

Yet he reminds even healthy eaters that it’s fine to indulge in treats occasionally. After all, a long life should be worth living, and food is one of its joys.