William Butler, multi-instrumentalist for Arcade Fire, enrolled in the Kennedy School’s midcareer master’s program in public administration to broaden and enhance the band’s award-winning humanitarian efforts.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Moving the needle

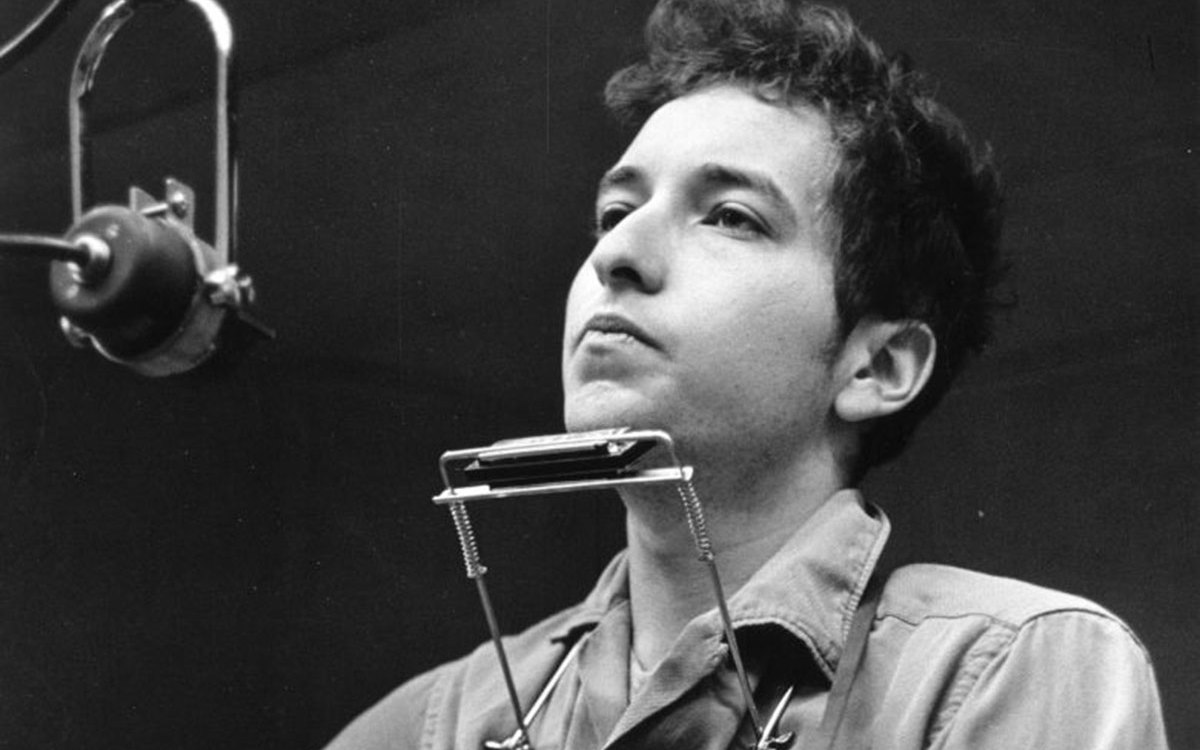

Arcade Fire’s Will Butler graduates from HKS to resume a musical career that also fuels humanitarian work

This is one in a series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

It took Will Butler a few years to find the time, but where to continue his education was never in question.

“Part of why I’m at a policy school and not an art school is because I care about context, and the context of the humanity enriches the art,” said Butler, a multi-instrumentalist in the indie rock band Arcade Fire who graduates from Harvard Kennedy School’s (HKS) midcareer master’s program in public administration. “I don’t think historicizing art has to cheapen it. I think you can be of two minds [on] things.”

Butler first applied to HKS in 2012 but band commitments intervened. After deferring a second acceptance, he began his studies in fall 2016 and found it valuable to be in an academic environment during and after the election.

“It’s nice to be in a space hearing how government works, and foreign policy works, from the horse’s mouth,” said Butler, whose areas of interest are international development and the state of America. “It feels very apropos to be plugged into that world.”

He said Arcade Fire’s purpose has never been simply about music.

“You try to be a human, and then it’s a bit of a mystery how the art is produced. We’ve always had to take time off and live just on a human level. That’s always been our method — engaging with the community and then questioning ourselves and then making art,” he said.

The band’s efforts to affect change helped point Will toward HKS. His older brother, Win, founded Arcade Fire with Régine Chassagne, whose family had fled Haiti for Canada during the Duvalier dictatorship. In 2007, the band began giving $1 from every concert ticket sold to Partners In Health. After a decade of sales (and engaging other musical groups to do the same through the nonprofit Plus 1) and having trained thousands of outreach volunteers, Arcade Fire helped raise more than $4 million, earning the band the 2016 Allan Waters Humanitarian Award in Canada.

“I came here to figure out how to help them better and, in a general sense, how to move this mission [forward], of caring for people who have less power,” Butler said. “It’s part of the same conversation that Haitians are having and Rwandans are having, and I’ll be doing it in a slightly more informed manner than just going around playing shows.”

The band, which will release an album this year and has scheduled a European tour this summer, typically plays to crowds of 10,000, a size Butler said makes him think about the way he interacts with them “that is real and human.” That may be why History & Literature lecturer Timothy P. McCarthy’s course “The Art of Communication” offered him so much insight.

“After the election, I felt like I need to talk to everybody,” Butler said. “It’s a rare resource to have (such a big stage). An artistic experience is not nothing, but maybe there is more to be done.”

He plugged into the School’s diverse cohort, connecting with students from Nigeria and Azerbaijan and hearing freedom-of-speech arguments from a range of voices that included a student from Singapore and former Obama administration officials.

“Part of what has been great about being here and being a little older,” said Butler, who is 35, “is not caring terribly much about formal constraints or hierarchy. I really see everyone as my peer. That’s how I approach music and performance as well. It’s communicating with as opposed to performing for.”

Butler will return to the stage with a deeper appreciation of how music is so closely tied to issues of race, equality, and social justice. In the fall course “Political Revolutions” with Leah Wright Rigueur, assistant professor of public policy, Butler studied Detroit, learning about the black struggle for civil rights, the white citizens’ councils, and the 1967 riots in that city.

“Motown is three-quarters of a mile from where the riots started. It’s not a historical force. Marvin Gaye was recording ‘Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing.’ ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’ also happened. You can look at those songs from a policy lens and a political lens,” Butler said, “but you can also divorce them from that and hear them as an aesthetic event. I vote for engaging on all levels.”