Midwest summer storms threaten ozone, study warns

Similarities to polar erosion spark call for closer look at region

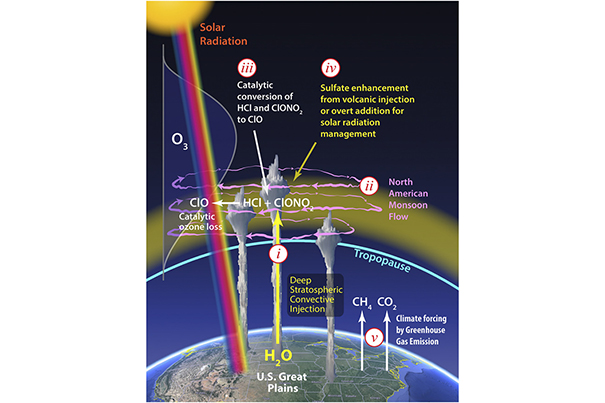

Storms common to the Midwest in summer create the same ozone-damaging chemical reactions found in polar regions in winter, according to a new Harvard study. And with extreme weather on the rise, people living in the region could face an increased risk of UV radiation.

Powerful storms in the Great Plains inject water vapor that, with temperature change, can trigger the same chemistry eroding the Arctic ozone, according to a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The paper was led by James G. Anderson, the Philip S. Weld Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

Researchers tracked on average 4,000 storms each summer penetrating into the stratosphere over the central U.S., a rate far more frequent than previously thought, sparking a call from the paper’s authors for weekly forecasts of ozone loss.

“These developments were not predicted previously and they represent an important change in the assessment of the risk of increasing UV radiation over the (region) in summer,” said Mario J. Molina of the University of California San Diego, the 1995 Nobel Prize winner in stratospheric chemistry, who was not involved in this research.

The study’s authors say the lack of data recorded on ozone loss in the Midwest has curtailed researchers’ ability to forecast increases in UV radiation in the region, heightening risk for residents of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, the Dakotas and states that border the Great Plains.

“Rather than large continental-scale ozone loss that occurs over the polar regions in winter characterized, for example, by the term Antarctic ozone hole, circumstances over the central U.S. in summer are very different,” Anderson said.

Stratospheric ozone is one of the most delicate aspects of habitability on the planet, researchers point out, with only marginally enough to protect humans, animals and crops from UV radiation.

“Every year, sharp losses of stratospheric ozone are recorded in polar regions, traceable to chlorine and bromine added to the atmosphere by industrial chlorofluorocarbons and halons,” said Steven C. Wofsy, the Abbott Lawrence Rotch Professor of Atmospheric and Environmental Science at SEAS and co-author of the study. “The new paper shows that the same kind of chemistry could occur over the central United States, triggered by storm systems that introduce water, or the next volcanic eruption, or by increasing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. We don’t yet know just how close we are to reaching that threshold.”