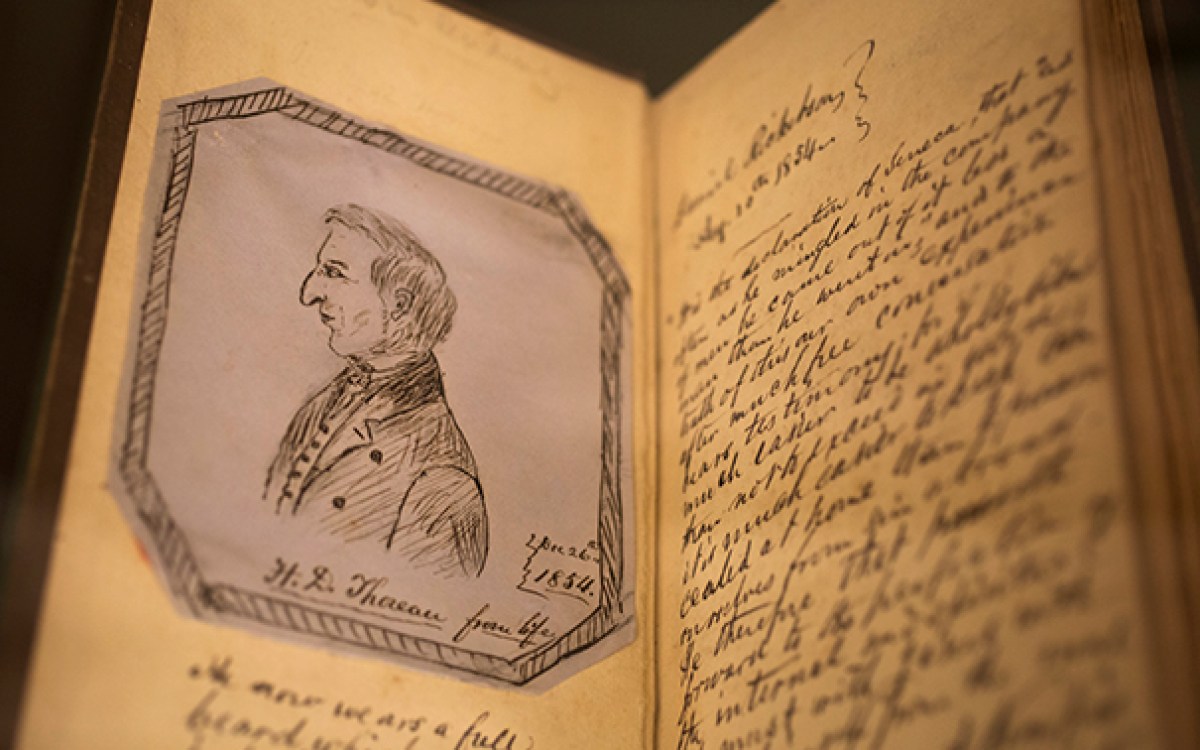

On Thoreau’s 200th birthday, a gift for botany

Harvard University Herbaria posting digital images of Concord specimens

Henry David Thoreau wandered the forests and fields around his home in Concord, making the observations that brought him fame. He also collected specimens of the plants he found there, preserving about 820 for identification and study.

That collection, which today resides in the Harvard University Herbaria, is something of a botanical time machine. In combination with the naturalist’s extensive notes about when and where they were collected, the specimens can provide insight about the changes between Thoreau’s time and now.

“They were his personal herbarium that he was using to make identifications and to record and document the flora of the Concord region,” said Charles Davis, a professor of organismic and evolutionary biology and director of the Harvard University Herbaria.

In honor of Thoreau’s 200th birthday, on July 12, hundreds of new images of his specimens, along with the data associated with them, are being posted online, part of a larger effort to digitize and open to the public the 5.5 million dried plant specimens in the Herbaria’s collection.

“I think it’s fair to say that the data that live inside these cabinets has been dark for far too long,” Davis said. “My vision for the collections is that we make everything online and accessible to the world.”

That larger effort has meant adopting a new “open-access digitization policy,” available on the Office for Scholarly Communication website, that puts most of the images — excepting those whose copyright is held by other institutions or individuals — in the public domain.

“The Herbaria is the first Harvard museum to adopt an open-access policy for its digitization projects,” said Peter Suber, director of the Office for Scholarly Communication. “Lifting restrictions from the bulk of its digital reproductions will bring this unique botanical collection to a global audience, and advance the Herbaria’s mission of research and education.”

The digitization project will allow scholars from around the world to view the collection online, in some cases providing enough information to make a trip to Cambridge unnecessary.

More like this

“Our mission is to enrich and expand knowledge,” said Michaela Schmull, the Herbaria’s director of collections. “This includes not only displaying the richness of the collections, but also facilitating easy access to the information that was in the past, mainly due to the lack of resources, only accessible by visitor appointment or by official loan request. Today’s online access is not only giving professional botanists and students the chance to use the information for any type of research question, but enables everybody who is curious about our environment to explore the past, present, and future from any place in the world that has internet connection.”

Davis expects the digitization effort to increase use of the physical collection because researchers will be better able to see what’s there and to understand how particular specimens might help them answer scientific questions.

“We use these specimens regularly for DNA extraction and careful morphological assessment. Obviously, you can’t extract DNA from a photograph and some important details are not obvious from a photo,” Davis said. “My hope for digitization is not only that we unlock these resources, but that it will open new lines of scholarship and we may actually also increase attention for the physical specimens themselves.”

More than 600,000 specimens of vascular plants, fungi, lichens, bryophytes, and algae have been digitized so far. While the fungal and algae projects continue, new efforts are focused on the Herbaria’s collection of dried vascular plants, which are pressed and flattened and can be represented well in two dimensions.

Other collections, including the famed Glass Flowers (officially the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants) and ceremonial headdress artifacts from the Economic Herbarium of Oakes Ames, present different digitization challenges, Davis said. Those will be tackled once the dried plant collection — which makes up the vast majority of Herbaria holdings, in both number and bulk — is complete.

“These collections are priceless. They’re our best representation of where nature lives or has lived,” Davis said. “The exciting thing is that we’re finding all sorts of new ways of exploring these resources, using them in ways they were never originally intended. And the beauty is that as other organizations make their collections accessible, the possibilities grow even larger.”

Jonathan Kennedy, who as biodiversity informatics manager at the Herbaria is overseeing the digitization effort, stressed the sheer size of the project.

“Anything you do multiplied by 5.5 million is going to be expensive or impact services,” Kennedy said. “We worked hard to shave off every second of our imaging process and to decouple the many parts of the workflow so that we could scale up or down as needed. In the end, our process should be flexible enough that we can keep access to the collection while we undertake digitization.”

Interpreting the data associated with each specimen has been a particularly challenging part of the process, Kennedy said. Among the handwritten labels, some are more than a century old.

“There is a significant amount of knowledge and research that goes into interpreting data that was handwritten on a label 100-plus years ago, so digitization of these resources has traditionally been a very incremental process,” Kennedy said. “However, with the growing need to make scholarly resources accessible online, as well as growing opportunities in data sciences, there are increasing reasons to make broad cross sections of our collection available digitally.”

The current digitization effort is a continuation of the Herbaria’s early embrace of the digital age, Davis said. The Gray Herbarium Index, a database of nearly 300,000 records of New World vascular plants, was an invaluable resource for scholars for decades before it was put online in 1992, during the early days of the web.

“The Herbaria was a lesser-known pioneer in the realm of opening digital access to collections,” he said. “This is a continuation of that tradition.”