Giving Harvard a little more groove

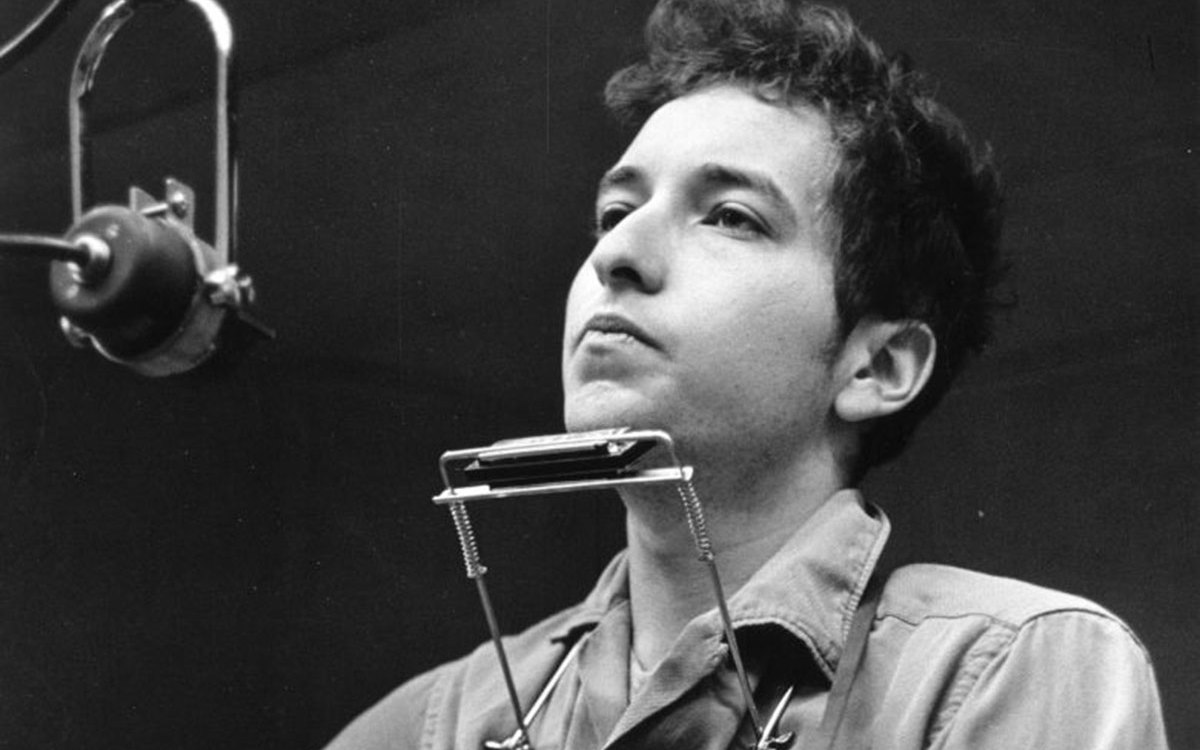

New professor Braxton Shelley brings deep belief in the power of music

Braxton Shelley believes in the holy power of sound.

Harvard’s newest assistant professor of music brings years of experience as a composer, pianist, choir director, and minister to his intellectual pursuit of spiritual music.

“Having a strong academic study of religion beside the vocational life has enriched me; it adds to the music,” said Shelley, who is also the Stanley A. Marks and William H. Marks Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute. “There’s another level of rigor and sophistication that I think matters because a lot of what animates gospel music is inseparable from the articulation of belief.”

The Rocky Mount, N.C., native, whose “Groove” may be the best-named course in the fall catalog, said that all of his formative music experiences took place in church. His first piano teacher was the church musician, and by age 9 Shelley played piano or organ every Sunday at Rocky Mount’s Church of the Open Door-Baptist.

Being equally passionate about social justice, he planned to study law and become a politician, but a music theory course provided intellectual depth to the somatic understanding of sound he’d internalized for years.

“I knew chord symbols and how to talk about harmonies, but a lot of my early church playing was by ear,” said Shelley, whose second album “I’ve Gotta Tell It” comes out later this year. “A lot of the work is still by ear. Theory put words to what I felt. And at the same time, some of my brighter curiosities related to the social and religious phenomenon coalesced with my interest in music.”

Performing provides a constant source of inspiration, Shelley said, pointing to a 2013 concert at Mt. Level Missionary Baptist Church in Durham, N.C., as an example. The show featured original compositions by Shelley, including a fast-paced, groove-based song called “Mighty God” in which an ecstatic shout-and-dance broke out. Shelley sees these moments as “sacraments, extensions of divine presence.”

“I was at the piano, watching what I spent a year and a half trying to put to words manifest before my eyes,” he said. “That was a nugget of experience that said to me, ‘Yeah you’re on to something.’”

Though he plays piano and organ, sings, and has a master’s in divinity and a Ph.D. in history and theory of music, Shelley said his musical strength lies as a composer.

“I have written songs during a church service, sitting at the organ playing,” he said. “I’ve written songs at the piano during practice time during chill meditative moments, and I’ve just heard melody or words and pitch and then I’ll go work it out.

“I’m really patient. I routinely let songs sit in my head six to eight months. I don’t write them down until they’re done, and I know when they’re done. I could finish a song if I wanted to, but I prefer them to work out themselves, so I wait to feel inspired and it’s kind of completely itself.”

In “Groove,” a graduate seminar, students will examine the interrelation of rhythm and movement across a historical span reaching back to 17th-century dances such as the passacaglia and chaconne.

“The phenomenon of groove is embedded in a long history of music and dance,” Shelley said. “At some level groove is thought to result from the interaction between instrument and/or performers. In this case, groove seems to be understood as both a feeling and a musical entity that facilitates the production of that feeling.

“In a broader sense, it’s a cut or ridge that facilitates movement, so I want to see what happens when we put together all of the conversations of the way we think of groove.”