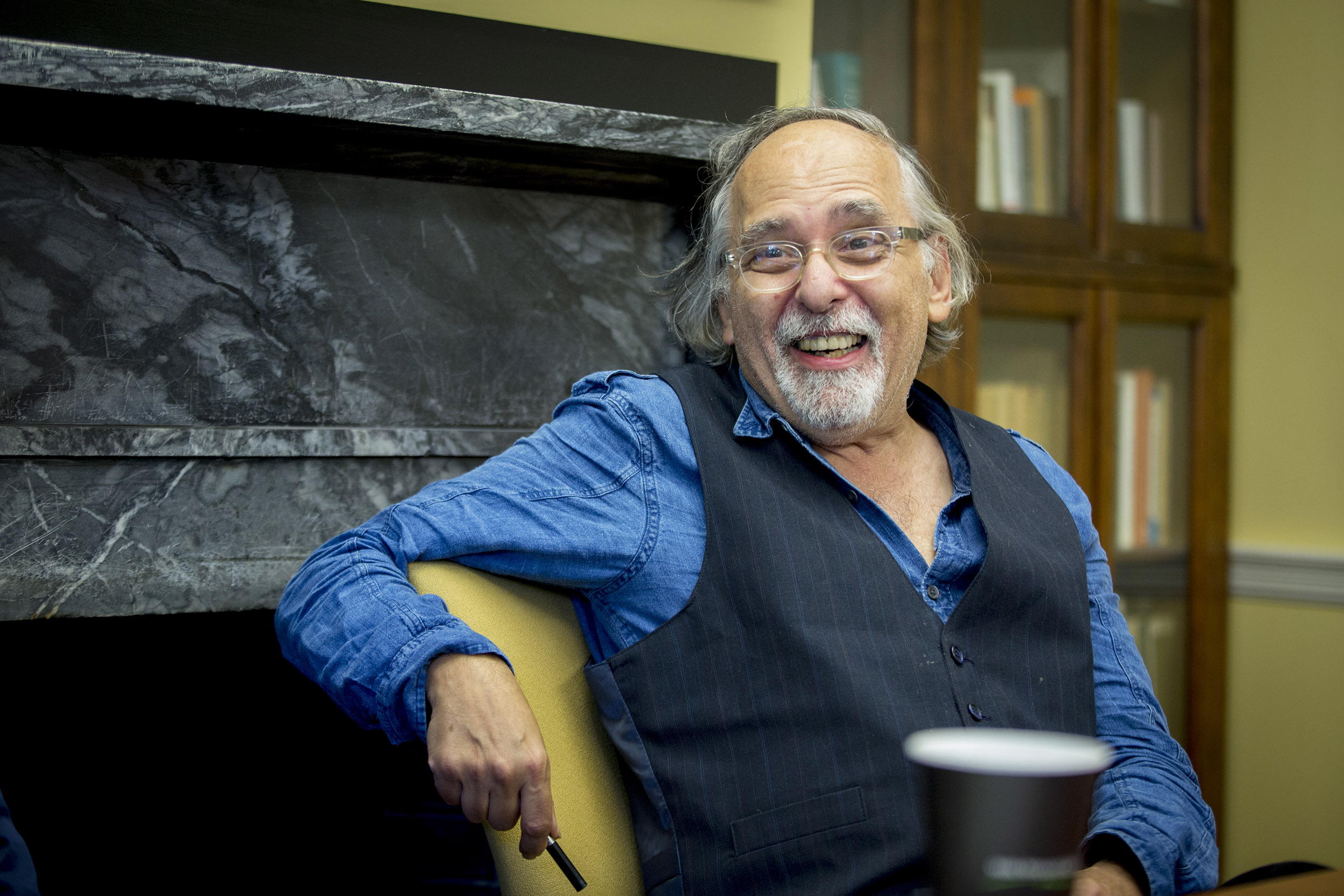

“I wanted to find a story worth telling,” cartoonist Art Spiegelman told a comparative literature class about his Pulitzer Prize-winning “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale.”

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Fathers, killers, God, and ‘Maus’

Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist Art Spiegelman ponders art, existence, and Jewish identity in conversation with students

For many, the cartoonist Art Spiegelman’s “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” is not just an unshakable Holocaust narrative, but a classic engagement, and struggle, with Jewish identity.

Today, more than 30 years after the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel appeared, Spiegelman still has trouble making sense of his religion and culture. “The relationship is fraught,” said the 69-year-old during an early-semester visit to Harvard. “I don’t know how to take solace in religion.”

Speaking candidly to a class of comparative literature students, Spiegelman was animated on topics ranging from his sense of responsibility to future generations to post-Charlie Hebdo life as an artist. Wearing his signature vest but not his signature fedora, his responses blended the humorous and the heavy.

Spiegelman described Vladek, the father protagonist in “Maus,” as “the Larry David of Auschwitz.” Of his own Jewish identity crisis, he acknowledged “a tribal connection” and called himself a “spokesperson of Jewishness,” but emotional conflict followed, especially when the conversation turned to life and death.

Recalling surgery for a brain cyst a few years ago, he confided: “I thought that was that.”

“Do I find religion like you’re supposed to at the end of your life?” he wondered at the time. “About the only thing I could find to take solace in was the church of the absurd, the existential. … I can’t find it in Jewishness.”

“Maus,” set in New York in the late 1970s with flashback panels to World War II, crosses genres from biography and memoir to historical fiction, with animated mice, cats, and pigs telling the story of Spiegelman and his father, a Holocaust survivor. Theirs is a relationship shadowed by the pain of the past.

Allie Freiwald ’18, who is writing her thesis on representations of the Holocaust in art and culture, was amused that Spiegelman was “more comfortable identifying as a Cartoonist-American,” but said later that she was “somewhat troubled” that he questioned his Jewishness.

“I understand, albeit through my vastly different frame of reference and set of life experiences, what it is to doubt religion, and Judaism in particular, in our secularized diaspora,” Freiwald said. “There is ‘Holokitsch,’ as he calls it, and, in my opinion, plenty of other Jewish kitsches. And there is a weird mixture of pride and revulsion upon reflecting that someone or something becomes more attractive by virtue of its inclusion in the ‘tribe’ — how did we inherit that?”

Such is the struggle of the mind behind “Maus.” Inside Spiegelman is both a legendary cartoonist and a boy haunted by his family’s Holocaust story. “When I was growing up, it’s not such a good idea to be a Jew. They killed you.”

Spiegelman said that “Maus” was not intended “to make the world a better place.”

“It’s a cartoonist’s job to tell stories. I wanted to find a story worth telling,” he said, adding that parent-child relations were also in play. “I wanted to be in touch with my father. I didn’t want to be in touch with my father.”

The night before his meeting with students, Spiegelman engaged with an equally captivated audience at Sanders Theatre in a Center for Jewish Studies-sponsored talk titled “Comix, Jews ’n Art? Dun’t Esk!!”

Hillary Chute, a former visiting professor and junior fellow at Harvard and now an English professor at Northeastern University, introduced him as “brilliant and brilliantly uncompromising.”

“Spiegelman has always been reluctant to identify with … any group besides cartoonists,” she said, recalling that there were many times while they were collaborating on the “Maus” companion “MetaMaus” (2012) when he told her he could not continue. “He said to me in exasperation, ‘Anything about Jews, guilt, or war? I don’t want to talk about it.’”

Spiegelman took the audience on a historical tour of comics, folding stories about favorite artists into personal anecdotes. As a kid, he perused Harvey Kurtzman’s Mad magazine “the way some kids studied Talmud.”

In the classroom, Isaiah Michalski ’21, who is from Germany, asked Spiegelman if there was anything he wouldn’t draw. The artist mentioned ways he has spoken out in both comic form and at protests against the police killings of Amadou Diallo and Eric Garner, and the Charlie Hebdo massacre.

“Artists should draw anything they want to draw and be more sensitive,” he said. “I think it’s important to find that balance between anger and empathy.”