Harvard Professor Winnie Yip and Burke Fellow Jose Figueroa are working with researchers to improve health care in some of China’s poorest regions.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Researchers work to fill gaps in Chinese health care

Large-scale experiment focused on improving outcomes for poorer patients

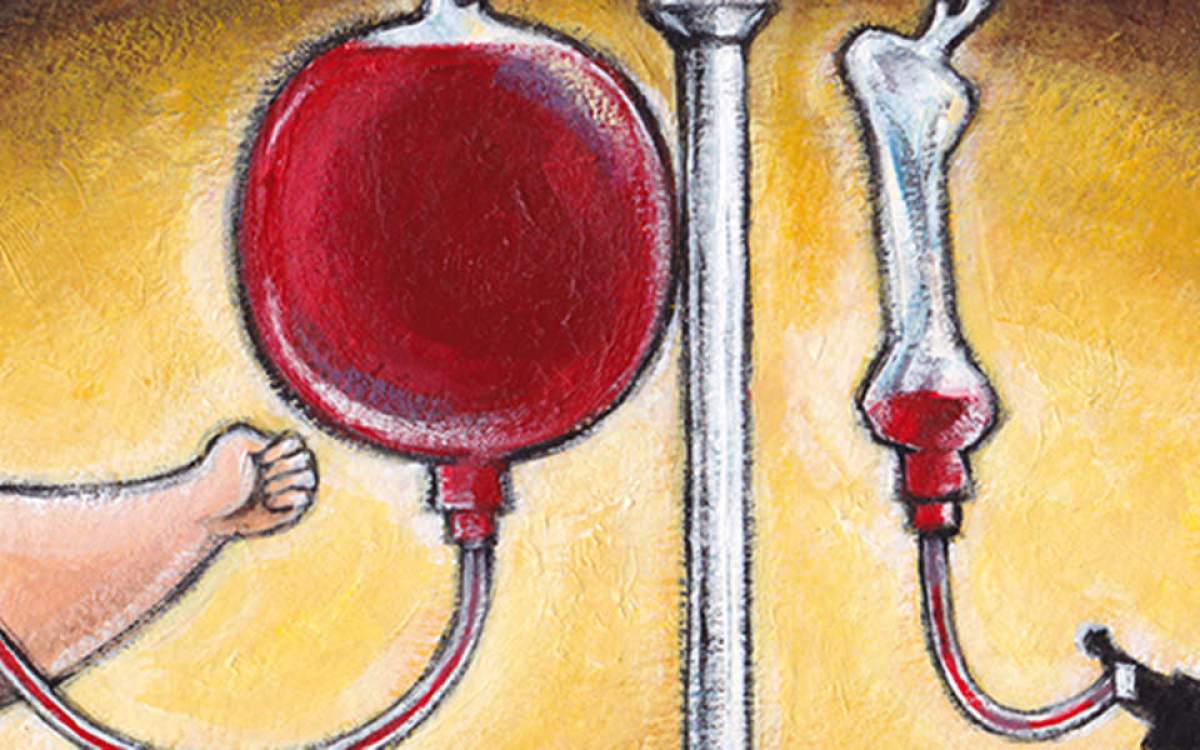

Harvard researchers have designed a system that aligns financial incentives for physicians and hospitals with key measures of performance, hoping to improve health care for millions of patients in some of China’s poorest regions.

The effort follows on the Chinese government’s 2009 health care overhaul, which more than tripled spending and implemented an insurance system aimed at ensuring access for 1.2 billion people. The reform made insurance universal and increased participation in the health care system, but without ensuring improvements in quality of care, said Winnie Yip, professor of the practice of international health policy and economics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. To accomplish that goal, the government is working with a research team led by Yip on a large-scale experiment at county hospitals in the provinces of Guizhou and Ningxia.

The initiative — called APPROACH, for Analysis of Provider Payment Reforms on Advancing China’s Health — is being conducted in collaboration with provincial governments and with teams from Chinese universities. It seeks to alter a system whose incentives are “mal-aligned,” according to Jose Figueroa, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and part of the project team.

China’s fee-for-service health care system leads to inappropriate prescriptions, unnecessary tests, and longer-than-needed hospital stays, Figueroa said. And because not every procedure is covered, the system also drives up out-of-pocket expenses for patients.

In the experimental system, the public insurance program pays hospitals a prospective budget based on the county’s disease profile, with 30 percent withheld and paid at six-month intervals according to whether the hospital has met specific quality measures known to improve care for common health conditions. Figueroa is helping devise those measures as a Burke Fellow at the Harvard Global Health Institute.

The plan is being implemented at 50 hospitals in 28 counties, Yip said, and is part of a broader effort to improve care at different levels of the nation’s health care system.

“A major area of my research is concerned with how to use financing and provider payment to leverage delivery of more effective care,” Yip said. “In China, my work is always conducted in partnership with a team of China-based researchers and governments.”

Measures on which hospital payments are based include use of a standard surgical checklist and routine tests of blood oxygen levels in pneumonia patients.

Though the measures have been proven in a Western setting, it’s important during the pilot phase to ensure that they translate to rural Chinese hospitals, Figueroa said. Differences in standards and practices raise the chances of technical misunderstandings that can influence performance and reporting among local doctors, affecting results of the trial and the hospital’s subsequent payment.

“Before we start holding these hospitals accountable, we need to ensure we pick good enough measures that are true reflections of the quality of care that these hospitals are giving,” Figueroa said.

Another challenge, Yip said, is accurate and timely data collection. In addition, hospital managers have needed time to transition to a prospective budget payment system from fee-for-service. Changing minds and behavior is not easy, Yip said.

Pay-for-performance systems are controversial because of doubts over whether they actually improve care. In the U.S., pay-for-performance reforms in the Affordable Care Act have lowered readmission rates, but have been ineffective in other areas of care. The amount withheld — 1 percent to 3 percent — may be too small to drive change, Yip said.

The size of the Chinese experiment and the 30 percent withheld should provide significant incentives to alter behavior, she said. In addition, China’s strong central government both encourages experimentation and gives health care leaders the ability to scale up positive results and lessons learned.

“It’s really exciting because it’s very rare to have an opportunity to essentially design a health system,” Figueroa said. “The ability for scaling and dissemination is pretty incredible. Depending on the success of this program, it would be really cool to see it hopefully help other regions of China as well.”