Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library has acquired the papers of famed activist Angela Davis, including art, photos, public records, and other materials.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

A radical archive arrives at Harvard

With help from Hutchins Center, Schlesinger Library acquires papers of scholar-activist Angela Davis

For almost 60 years Angela Davis has been for many an iconic face of feminism and counterculture activism in America.

Now her life in letters and images will be housed at Harvard.

Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library has acquired Davis’ archive, a trove of documents, letters, papers, photos, and more that trace her evolution as an activist, author, educator, and scholar. The papers were secured with support from Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

“My papers reflect 50 years of involvement in activist and scholarly collaborations seeking to expand the reach of justice in the world,” Davis said in a statement. “I am very happy that at the Schlesinger Library they will join those of June Jordan, Patricia Williams, Pat Parker, and so many other women who have been advocates of social transformation.”

Jane Kamensky, Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Director of the Schlesinger Library, sees the collection yielding “prize-winning books for decades as people reckon with this legacy and put [Davis] in conversation with other collections here and elsewhere.”

When looking for new material, Kamensky said the library seeks collections “that will change the way that fields know what they know,” adding that she expects the Davis archive to inspire and inform scholars across a range of disciplines.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. said that he’s followed Davis’ life and work ever since spotting a “Free Angela” poster on the wall at his Yale dorm. Gates, the Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor, has worked to increase the archival presence of African-Americans who have made major contributions to U.S. society, politics, and culture. He called the Davis papers “a marvelous coup for Harvard.”

“She’s of enormous importance to the history of political thought and political activism of left-wing or progressive politics and the history of race and gender in the United States since the mid-’60s,” said Gates, who directs the Hutchins Center. “No one has a more important role, and now scholars will be able to study the arc of her thinking, the way it evolved and its depth, by having access to her papers.”

The acquisition is in keeping with the library’s efforts to ensure its collections represent a broad range of life experiences. In 2013 and 2014 an internal committee developed a diverse wish list, “and a foundational thinker and activist like Angela Davis was very naturally at the top,” said Kamensky.

Kenvi Phillips, hired as the library’s first curator for race and ethnicity in 2016, met with Davis in Oakland last year to collect the papers with help from two archivists. Together they packed 151 boxes of material gathered from a storage site, an office, and Davis’ home.

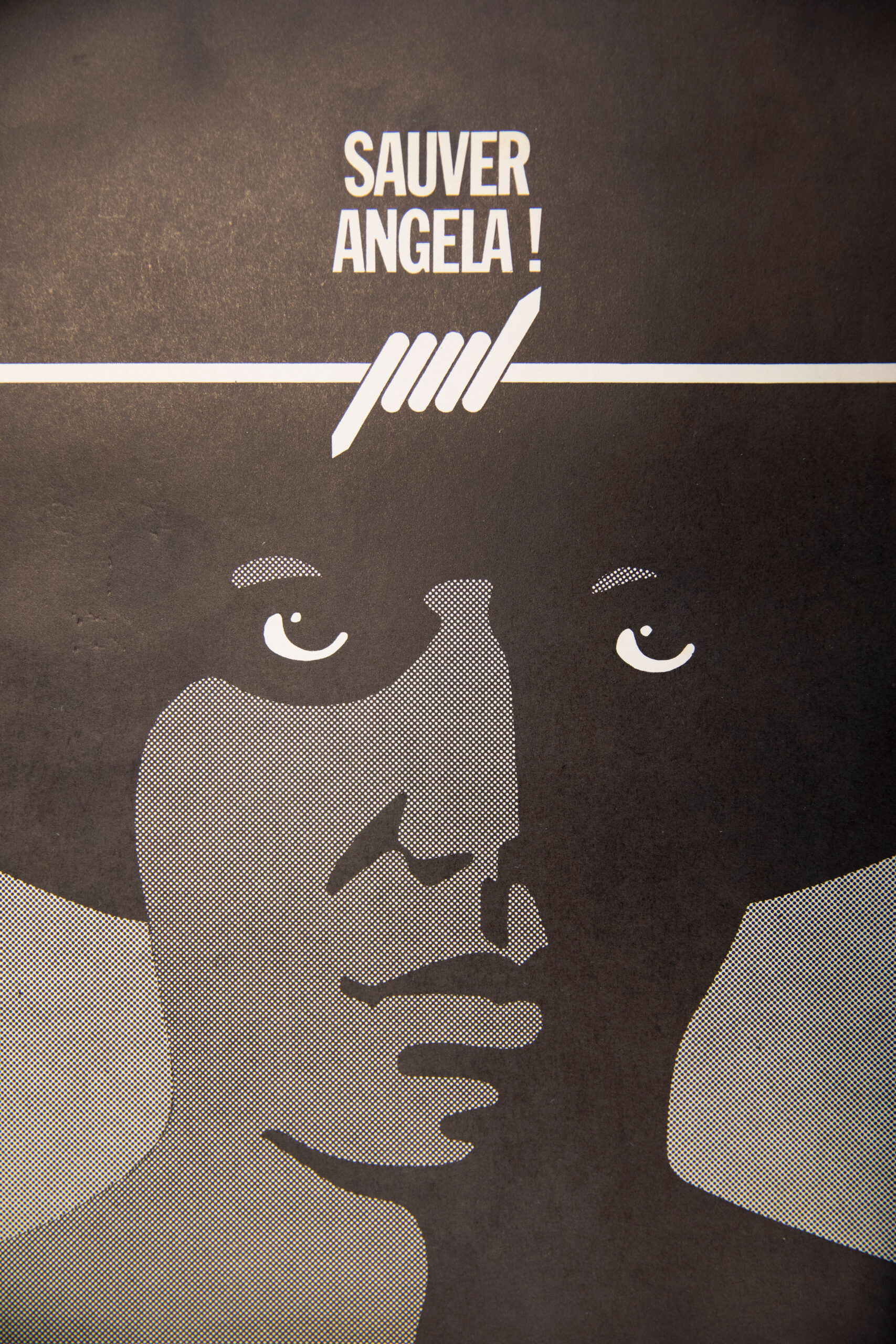

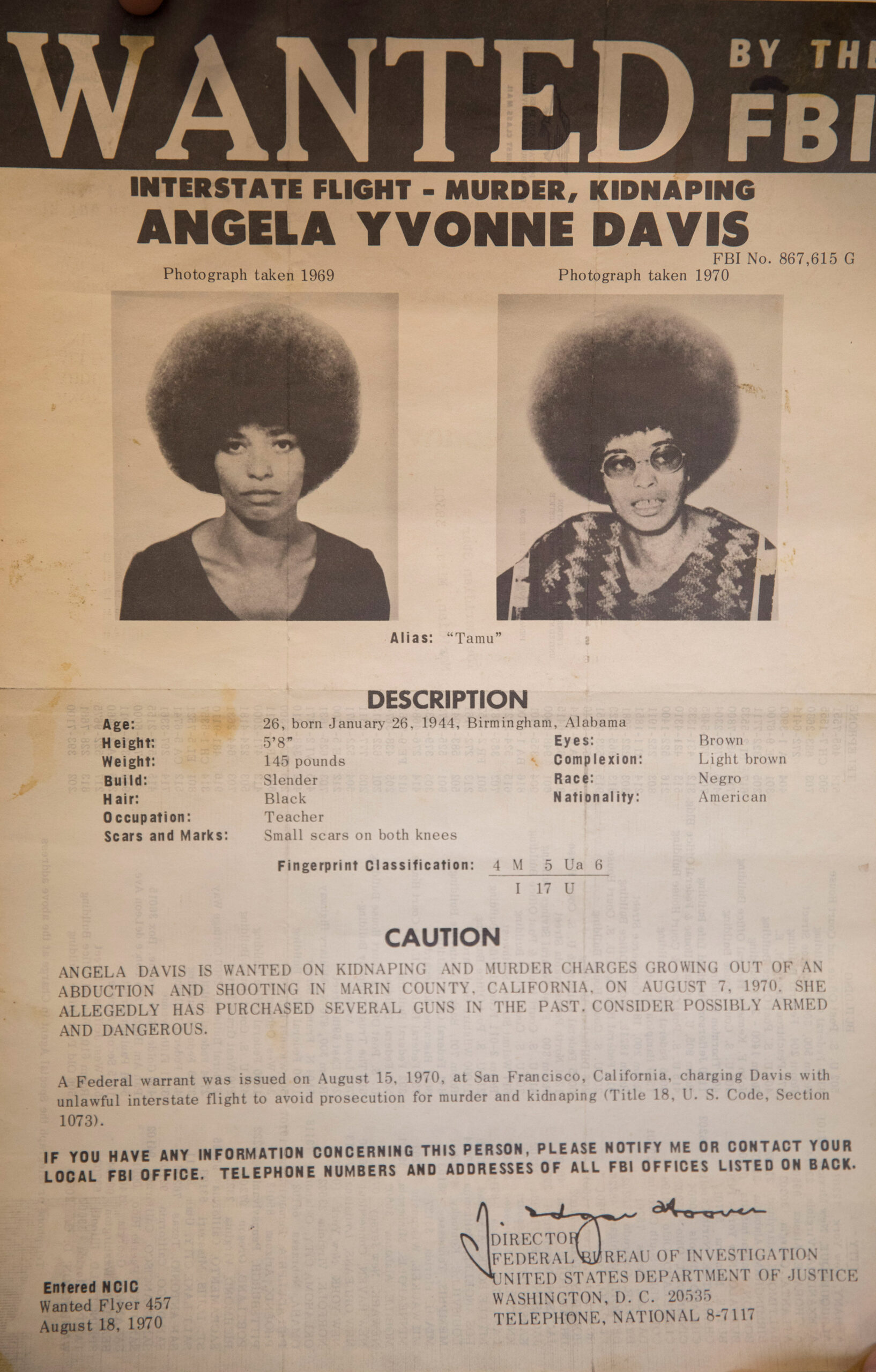

Image 1: The FBI wanted poster for Davis. Image 2: Davis (from left), her mother, Sallye, and author Toni Morrison.

Photos courtesy of the Schlesinger Library; (2) original photo by “Annie F. Valva, Santa Cruz California”

The collection includes a painting done for Davis by a death-row inmate in California, and a manuscript of her autobiography with edits by her friend Toni Morrison. There are numerous photos of the young Davis, including a shot of her posing with Fidel Castro. Reels of tape from her radio show “Angela Speaks” are also part of the archive, as is material related to her arrest in connection with the 1970 shooting of a superior court judge by an acquaintance who used guns registered in Davis’ name.

The arrest drew international attention. That interest is reflected in some of the Radcliffe materials, such as hundreds of letters that poured in for Davis while she awaited trial, and the flowers in paper, felt, and cloth that were part “A Million Roses for Angela,” organized by German supporters. Davis was acquitted of all charges in June 1972.

According to Kamensky, the number of Harvard scholars studying the problem of mass incarceration was of special interest to Davis, who visited campus in the fall of 2016 while considering the Schlesinger as a possible home for her archive. The papers include items connected to her work on mass incarceration and prison abolition, such as notes and documents related to Critical Resistance, the grass-roots organization she co-founded in 1997 whose mission is to “end the prison-industrial complex.”

“We haven’t had a kind of central formation for that work, and I think the collection can play a kind of catalyzing role,” said Kamensky.

One Harvard scholar long interested in such topics is Elizabeth Hinton, an assistant professor of history and of African and African American studies who in 2016 published “From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America.”

“Angela Davis has always been a pivotal figure in terms of the development of criminal justice reform activism,” said Hinton, who expects to use some of the Davis material in class.

A collection of pins in support of Davis and her causes, including her exoneration and presidential run.

Kevin Grady/Radcliffe Institute

“That will make history come alive for generations of students and hopefully inspire them to pursue social justice goals even after they leave Harvard’s campus.”

The arrival of the collection reminded Hinton of reading Davis’ autobiography when she was a high school senior, which “really illuminated a lot of issues and opened my eyes to the conditions that exist in American prisons and just inspired me to want to make important social justice contributions to society.”

Over the next year archivists will sort, document, and digitize some of the material in preparation for a series of events in 2019, including an exhibition and a Radcliffe conference featuring Davis that will focus on family, gender, and issues around incarceration.

While Kamensky acknowledged that Davis remains a controversial figure to many, she said that the activist’s life represents a core of the radical tradition in which “people with big ideas move the conversation by drawing fire. And she has taken that role as a lightning-rod thinker from a really tender age.

“By pursuing her papers Schlesinger is not asking the researchers to agree with her,” added Kamensky. “Archives do not prescribe a party line … [but] to tell histories true we need to see a full spectrum.”