Shelly Greenfield discusses a recent McLean Hospital conference that brought together academics, law enforcement, policy makers to generate ideas for combating the opioid epidemic.

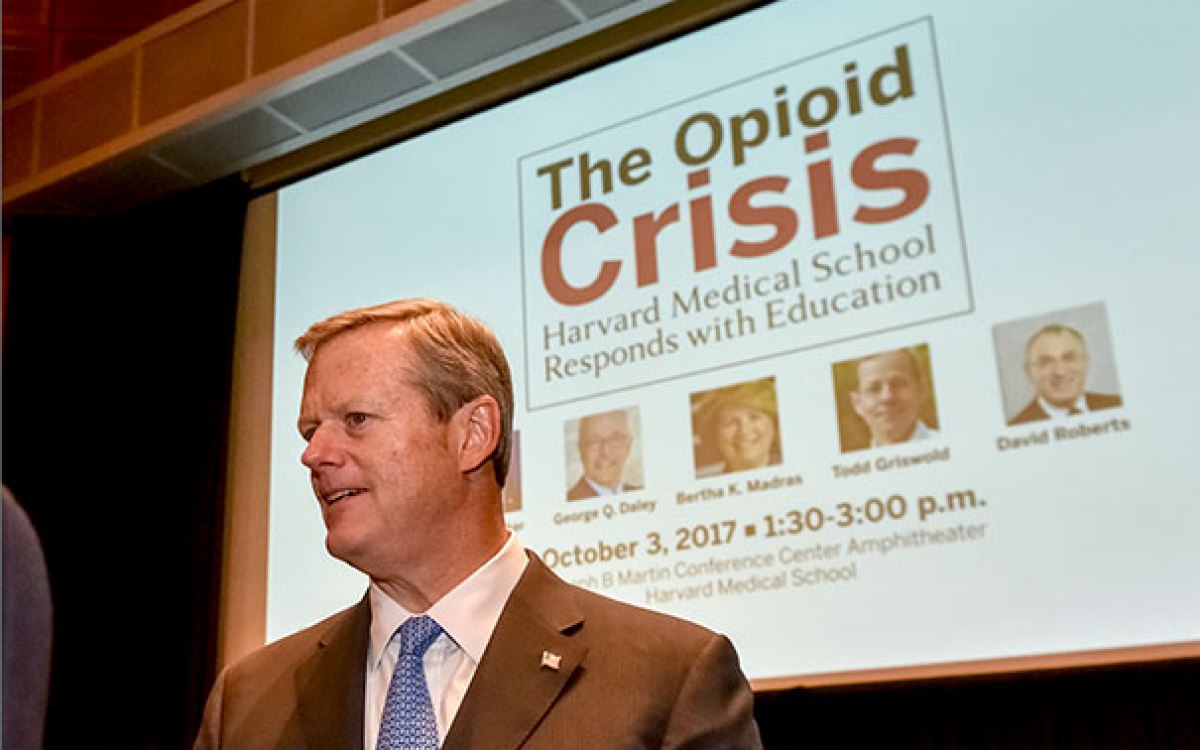

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Pulling our punches in opioid fight

Treatment access seen as dangerously inadequate in crisis that continues to claim dozens of lives a day

Representatives from government, law enforcement, health care, and community-focused nonprofits gathered in Boston this month to discuss the opioid epidemic devastating families across the country.

The meeting was organized by McLean Hospital’s Shelly F. Greenfield, the Kristine M. Trustey Endowed Chair in Psychiatry at McLean and a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School (HMS), and Kimberlyn Leary, an associate professor of psychology at HMS and associate professor of health policy and management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Among the speakers were Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker and state Secretary of Health and Human Services Marylou Sudders.

Greenfield provided a recap of the summit, along with insights on what works and what’s missing in policy, just as President Trump was preparing to announce a new plan for attacking opioid addiction, and only days after the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention reported a worsening of the crisis.

Q&A

Shelly Greenfield

GAZETTE: How did this meeting come together?

GREENFIELD: The idea was to have a public-private partnership to bring this meeting together. I began speaking with Nini Donovan, a principal of our co-sponsors, PricewaterhouseCoopers, in January 2017.

We saw a need to bring together people in states most severely affected by the opioid epidemic with colleagues from state and local and governments in other states, as well as with community organizations, law enforcement, health care, and policy makers. The goal was to discuss strategies we know actually work and to give people an opportunity to share what they’ve implemented, what they’ve seen work, and to make networking connections.

We selected 10 of the states that are very severely affected by the opioid epidemic, all six New England states and West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, and New York. These are not the only states that are severely affected in terms of the prevalence of opioid use disorder, but they have high death rates from opioid poisoning, also known as opioid overdose.

GAZETTE: Policies to enhance treatment and community response were a major focus of the meeting. Is there a sense that there are some things that do work, and is there any state that has the epidemic essentially licked?

GREENFIELD: We have not yet turned the overall tide of the epidemic nationwide. However, we know that there are effective strategies that have been implemented in Massachusetts and elsewhere. For example, in Massachusetts, in 2017, the state started to bend the curve with a decrease in deaths reported from opioid poisonings compared with 2016. I think it is promising to see this change in the right direction.

GAZETTE: Have other states seen the number of deaths decline at all?

GREENFIELD: I cannot speak specifically to statistics regarding deaths from opioid poisonings in other states. What I can tell you is that nationally, in 2015, overdose deaths exceeded 48,000. Preliminary statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention looked like, in 2016, these numbers increased, with more than 60,000 people who died from opioid overdoses nationwide that year. The 2015 statistics amount to 174 deaths per day, one every 8½ minutes, and these numbers increased from 2015 to 2016, which is really devastating and urgent. People often compare these statistics to deaths equivalent to a plane crashing on a daily basis.

GAZETTE: So having a state like Massachusetts, where you’re starting to bend the curve, is encouraging?

GREENFIELD: The state can legitimately feel positive that this is going in the right direction, and I hope we will continue to see this decline in the coming year.

GAZETTE: If there are things that we know work and if we do them in every single state, will it address the epidemic? Or is it a case where those things might help, but they’d still be not enough? What’s the state of knowledge?

GREENFIELD: There’s a lot to do that would make a big impact, but we haven’t implemented all of these strategies systematically in all states at this time. This is why we held this meeting.

One of the big takeaways from the first panel — moderated by Dr. Bertha Madras, who was deputy director of the federal Office of National Drug Control Policy under George W. Bush and who has most recently been one of the people on the opioid commission along with Gov. Baker — is that we know that opioid overdoses, relapses, and deaths are prevented when patients have access to effective treatment and most especially to medication-assisted treatment with any of the three FDA-approved medications. Approximately 35 percent of people with an opioid use disorder in treatment in the United States have access to these medications. That means that the majority of people with an opioid use disorder do not have access to medication treatment. When you have this many people dying, there is a very urgent need to extend access.

GAZETTE: These medications ease cravings without the high, essentially?

GREENFIELD: Medications can ease cravings, but they can do a lot of other things, such as assisting people in avoiding relapse and stabilizing their lives so that they can move forward.

Two of the medications for opioid use disorder can help with craving and also help stabilize the illness. Methadone is an agonist and buprenorphine is a partial agonist. The third medication, naltrexone, is an antagonist, which means it occupies the receptor and blocks the activity of any other opioid. So we have three FDA-approved medications, but most patients cannot gain any access to any of these medications. I think it would be unacceptable to us if we said that the majority of people with diabetes could not gain access to medications that can lower their blood sugar.

We also talked about naloxone, the short-acting antagonist used for reversal of overdose. When somebody overdoses on an opioid, it suppresses respiration. This is how people die from an overdose. Naloxone has high affinity for the opioid receptor and displaces other opioids off these receptors.

Naloxone is short-acting, but it is highly effective in reversing respiratory depression that can cause death. People receiving naloxone will go into immediate withdrawal, waking up and breathing. This allows people to be revived for long enough to be transported to an emergency department where they can be treated. Because naloxone is short-acting, sometimes people need another dose of naloxone within 30 minutes or so, depending on what type of opioid caused their overdose. So it is important for people to be transported immediately for emergency care. Having access to naloxone is very important in saving lives. I think of it as similar to using a cardioverter when a person has a cardiac arrest or arrhythmia.

GAZETTE: This was a policy-focused meeting, so if you had to summarize, what three policies were discussed that any state could implement and begin to make a difference?

GREENFIELD: I think a number of successful policies were discussed. One is that we need to expand access to medication treatment so that 100 percent of people affected by an opioid-use disorder have access to it, no matter where they live in the U.S.

There are a number of policies that would assist us in extending medication and psychosocial and behavioral treatments for opioid-use disorders. One important policy was described in the keynote delivered by Dr. Richard Frank. He said that states that expanded Medicaid increased access to treatment. This shows the need for insurance coverage, which includes Medicaid as well as commercial and private insurance. A second important policy is implementing care models that work. For example, one presentation described Vermont’s hub-and-spoke model of care. This has been responsible for ensuring that people in Vermont can access treatment on demand for an opioid-use disorder.

GAZETTE: So in addition to ensuring treatment programs are in place, it’s important to focus also on the ability of people to pay for treatment …

GREENFIELD: Without insurance coverage, people with opioid-use disorder will not have access to life-saving treatment. In states that have been successful in expanding insurance, under the Medicaid expansion, people did better, according to data presented by Dr. Frank.

The third policy would be making naloxone readily available in every possible place it can be. And you have to have first responders trained and able to immediately use it. There are also efforts to ensure that naloxone is available to family members and others who may be with people who use opioids, so that that person is not far away from somebody who could reverse an overdose immediately. If you can’t reverse the overdose, you may never have the opportunity to provide the necessary treatment so that this person can recover from the opioid-use disorder.

GAZETTE: Why haven’t these policies been implemented everywhere? Is it a matter of stigma? Budgets?

GREENFIELD: Stigma and discrimination are a big one. For many years, we’ve had a system of care for addiction and substance-use disorders that has never been adequate to provide Americans with treatment on demand for their substance-use disorder. We’ve always had a system that’s been underfunded and often outside the health care delivery systems for both mental health and general medical care. Without integrating substance-use treatment into mental health and general medical care it will be difficult to provide adequate treatment for people with opioid-use disorder and other substance problems.

GAZETTE: So the epidemic is hitting the system right where it’s weakest, essentially?

GREENFIELD: Exactly. This has been how treatment delivery has been in the U.S. for people with substance-use disorders for more than a half-century.

I would attribute a lot of that to stigma and discrimination. It contributes to people having a harder time accessing care because of the shame they feel, and their families feel. People are often very isolated.

Second is workforce capacity. We’ve not traditionally trained people in many of the health care disciplines to treat people with substance-use disorders. That includes the medical and nursing professions and other health care providers. We’ve not had adequate people trained to deliver medications and the associated behavioral and psychosocial treatments. So there’s been an effort to correct that and expand training and education for physicians and other clinicians.

Third is what we just talked about, people are uninsured or underinsured. So these three things together have made it tough to respond to this epidemic as fast as necessary.

The opioid epidemic is a very difficult but solvable problem. We have effective strategies but it’s going to mean implementing all these solutions we know about. It will also take the political will to do so — to say that we must solve this because our fellow citizens are dying.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.