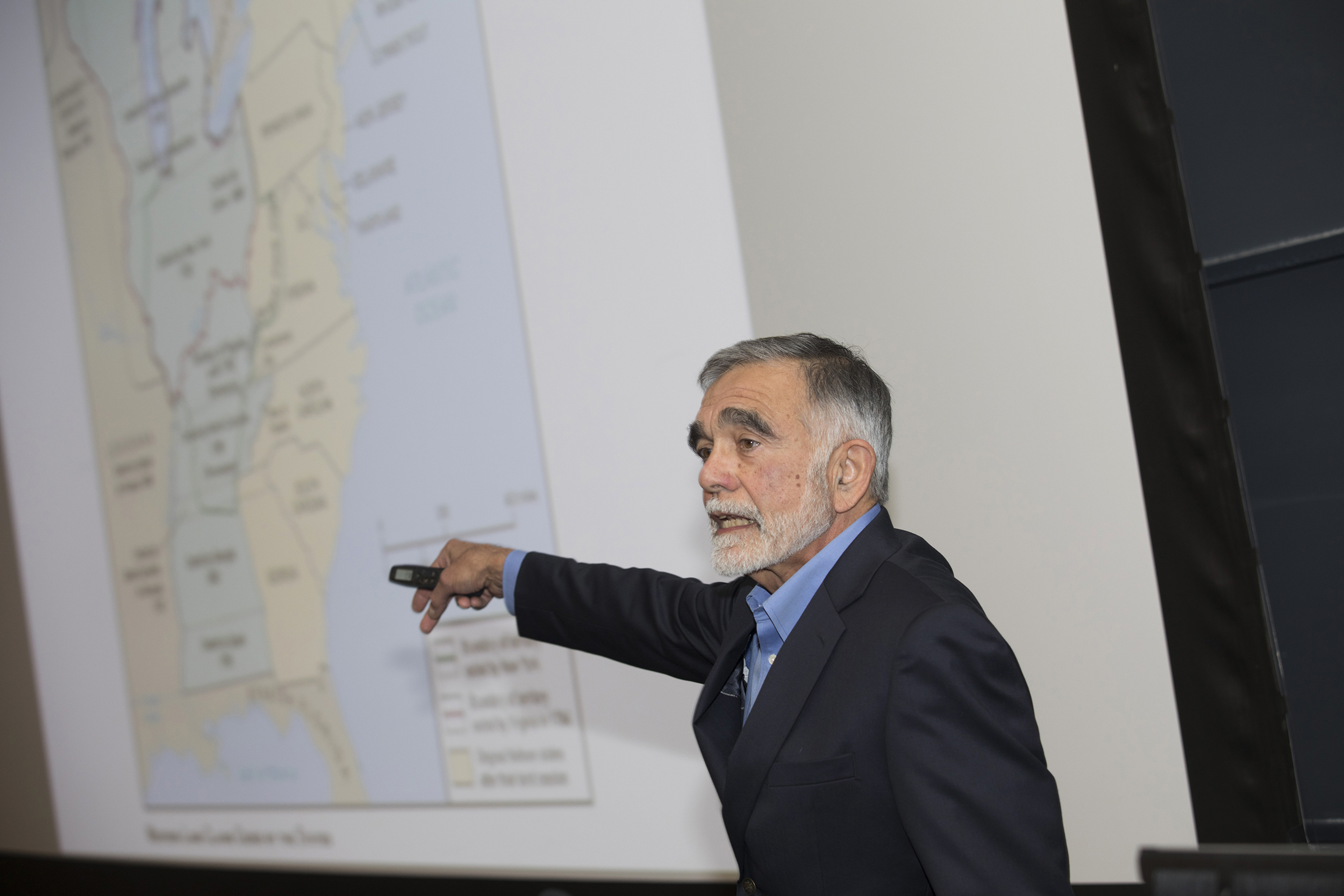

The Antiquities Act gives presidents power to protect federal land from development by creating national monuments, explained former solicitor for the U.S. Interior Department John Leshy. In December, President Trump used the law to reduce the size of two Utah natural monuments established by his predecessors.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Public lands ‘a priceless legacy’ for future

Former Interior official outlines disputes over their protection and use

A former solicitor for the U.S. Interior Department sought to set the record straight on public lands Wednesday, disputing Western activists’ views that U.S. government ownership amounts to an unfair land grab and reminding listeners that much of the land was the federal government’s from the beginning.

John Leshy, professor emeritus at the University of California’s Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco and Interior Department solicitor during the Clinton administration, said the divisiveness and partisan nature of the debate over public lands is relatively new, and also worrisome because it jeopardizes vast areas that have traditionally been managed for public benefit and enjoyment.

“Most of these lands … are open public access, managed for broad purposes — mostly protected purposes — for open space, for wildlife, for scientific study, for recreational access, for inspiration, for contemplation,” Leshy said. “There is nothing in the Constitution that says we have to keep these places, so it’s up to every generation of Americans to decide whether they want to keep them or not, and how they want them to be managed.”

The debate over federal lands was dramatically illustrated in 2014 during an armed standoff between government officials and ranchers led by Cliven Bundy, who owed fees from grazing cattle on federal land, money that Bundy claimed the government had no right to collect. In 2016, his son Ammon Bundy was among those who occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon to highlight their view that it is the state, not federal, government that should own such lands.

Among the laws in the sights of those who dispute federal land ownership is the Antiquities Act, because it gives presidents power to protect federal land from development by creating national monuments. Leshy traced the law’s use, which includes the protection of iconic U.S. landscapes such as the Grand Canyon, which Congress later designated a national park. In December, controversy over the law ratcheted up again when President Trump used it to reduce the size of two Utah natural monuments established by his predecessors. Bears Ears National Monument, created by President Barack Obama, was reduced by 85 percent, and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, on which Leshy worked as solicitor, by 45 percent.

Leshy spoke as part of a discussion about the act, which was passed in 1906 and first used by President Theodore Roosevelt to protect Devils Tower, which Congress subsequently made a National Park. The law allows presidents to set aside land with “historical or scientific significance,” and is currently at the center of several lawsuits filed over Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante that argue the measure does not give Trump the power to reduce the size of previously designated monuments.

The event, in Harvard’s Northwest Laboratory, was sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and introduced by its director, Daniel Schrag, the Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology and professor of environmental science and engineering. It featured a discussion by environmental law expert Richard Lazarus, the Howard and Katherine Aibel Professor of Law, and Terry Tempest Williams, writer-in-residence at Harvard Divinity School.

Federal management of public lands is as old as the nation, Leshy said. Further, there might not have been a nation without a compromise that involved federal ownership of large tracts of the eastern United States. Before the U.S. Constitution was drafted, states argued over the nation’s earlier effective constitution, the Articles of Confederation. A dispute had arisen between states that had claims to lands to the west of the original 13 colonies and those that did not. The dispute was resolved, Leshy said, by those states with claims giving them up to the new federal government.

Over time, Leshy said, the federal government took possession of large tracts of territory as the nation expanded, managed those lands to benefit the people there, and promoted areas’ growth into statehood.

“The nation wasn’t formed until the founding generation decided the national government was going to take ownership of a lot of land,” Leshy said. “There was no intention, from the very beginning, that as new states were formed they would automatically become entitled to all the U.S. public lands inside their borders.”

Today, Leshy said, the U.S. government owns one of every three acres in the country and manages them for communal purposes. That includes everything from smaller tracts holding lighthouses and military bases to large national parks, national forests, national wildlife refuges, and regions open to public use, including some areas leased to commercial interests.

Four agencies manage much of the land: the Bureau of Land Management, the National Forest Service, the National Park Service, and the Fish and Wildlife Service. Though some land is leased for grazing, oil and gas extraction, mining, and other commercial purposes, Leshy said that’s a “relatively small percentage” of government-owned land.

The Antiquities Act has been used more than 100 times by presidents of both parties and provided initial protection for some iconic landscapes, including Arizona’s Petrified Forest, Utah’s Natural Bridges and Bryce Canyon, Wisconsin’s Mount Olympus, New Mexico’s Carlsbad Caverns, California’s Death Valley, and Glacier Bay and Denali in Alaska.

In many cases, Leshy said, local governments and citizens have supported the land’s protection, even donating their own land or raising money to purchase property in order for it to be set aside. And, Leshy said, though activists argue that state governments should take over land management, many states don’t want the additional cost, including the growing tab to fight wildfires.

“This was not only done with local consent, with local petition, but often with local money,” Leshy said. “This is an American enterprise from the grassroots up.”

“There is nothing in the Constitution that says we have to keep these places, so it’s up to every generation of Americans to decide whether they want to keep them or not, and how they want them to be managed.”

John Leshy

Lazarus also discussed the lawsuits by environmental activists that Trump’s actions have prompted. Each side has good arguments, he said, but none that are clear winners. Some critics have argued that the law’s language appears to give the president power to establish but not shrink or abolish monuments. Lazarus said that reading would run afoul of a basic understanding of how presidential power works. It should also give people pause to think about a decision that winds up giving a president power to do things that future presidents can’t undo.

Lazarus and Tempest Williams agreed with Leshy’s assertion that the issue is ultimately a political one and that its resolution lies in the hands of voters and of citizens who decide to get involved and run for office.

Tempest Williams said one measure of the success of federal land management — and of how badly people desire the respite that the lands provide — is how crowded the parks are. When she heard of Trump’s action to shrink the two monuments, Tempest Williams said, she was angry and consulted tribal leaders who have a role managing Bears Ears. They told her that the need now isn’t for anger, but rather to gain a deep understanding of what is driving the dispute.

“I feel devastated, heartbroken, furious, and energized,” Tempest Williams said.

Leshy said the management of public lands for public good is one policy that he thinks the federal government has gotten right, allowing Americans living now to bequeath spectacular, unspoiled landscapes to future generations. He quoted libertarian activists who oppose federal management of the areas, saying they are “political lands,” a characterization with which Leshy agreed.

“It’s a priceless legacy, really, to hand down to succeeding generations. … It’s the best example of government long-term thinking I know of,” Leshy said. “Here’s a political success story, and frankly, in this very sour, cynical time we live in, I think it’s a success story worth savoring. We don’t normally think about the government doing something wonderfully visionary and successful, and this is one to treasure and savor and acknowledge.”