New Yorker music critic Alex Ross ’90 is writing a book that examines Richard Wagner’s influence, and explores if and how it is possible to separate a controversial artist from his oeuvre.

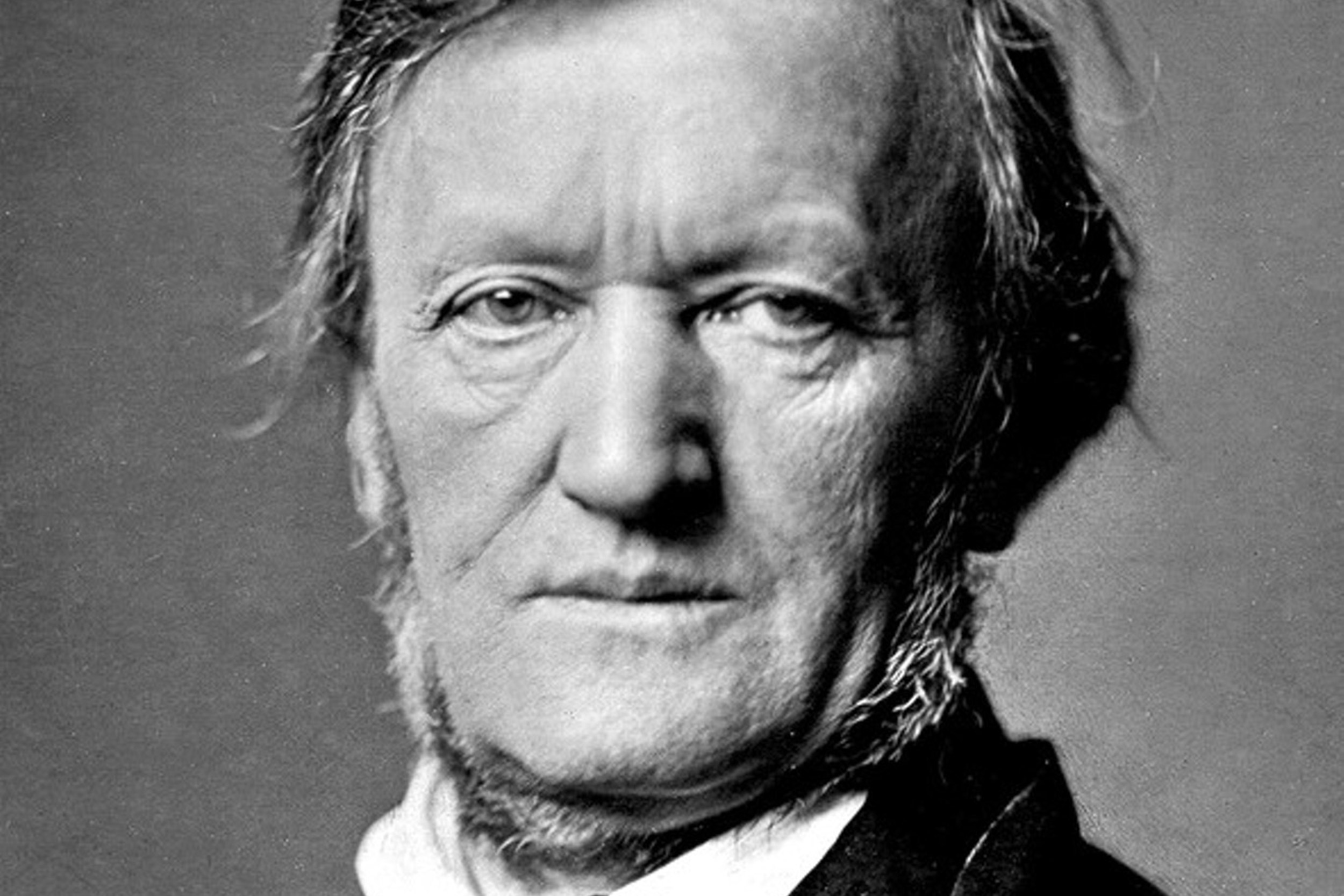

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

When the genius is also a symbol of hate, where does that leave us?

Work of 19th-century composer Richard Wagner, embraced by Hitler, ‘requires the most active and critical kind of listening,’ says author Alex Ross

Can you love the art but hate the artist? That vexing question, a thorn in the side of critics and connoisseurs for generations, has resurfaced repeatedly in recent months in the wake of the #MeToo movement.

New Yorker music critic Alex Ross ’90 waded into the discussion on Thursday at Harvard’s Paine Hall, an airy performance space where a frieze spells out the names of some history’s most revered men of music. Delivering the Music Department’s 2018 Louis C. Elson Lecture, Ross homed in on one of those men, German composer Richard Wagner, a titan of 19th-century culture whose creative genius has long been complicated, and often overshadowed, by his anti-Semitism.

For 10 years, Ross has been at work on “Wagnerism: Art in the Shadow of Music,” a book that explores the composer’s influence on artistic, intellectual, and political life.

“It’s a massive subject because Wagner may be, for better or worse, the most widely influential figure in the history of music,” said Ross, who counts Baudelaire, Du Bois, Eliot, Kandinsky, and Mann among the artists and writers who fell under the composer’s spell.

“Wagnerian” has become a synonym for “grandiose, bombastic, overbearing, or simply very long,” added Ross, noting that the term has been applied to everything from monsoons to “Fight Club” to “the tantrums of Tennessee Williams, according to Tennessee Williams himself.”

“Yet of the various Wagnerisms, the one with which most people are familiar is the Nazi version,” said Ross, referring to Hitler’s embrace of the composer’s work.

If that idea is indisputable, Ross thinks it is less clear whether Wagner’s anti-Semitism laid the foundation for Hitler’s hate. He also questioned the depth of Wagner’s presence in Nazi culture.

Hitler was introduced to Wagner early in his life, but his radicalism didn’t begin to take shape until years later, during his service as a German soldier in World War I. And though his rhetoric may have echoed Wagnerian ideas, there’s little evidence that the Nazi leader “absorbed Wagner’s more challenging themes,” said Ross, who sees the composer’s political influence as “greatly overstated.”

Instead of dwelling on this disconnect, the author is most interested in “how the cult of art resonates into our own time and how we might learn from its persistence.”

The prevalence of Wagner’s music in popular culture, including its use in films such as the racist epic “Birth of a Nation” and the Vietnam saga “Apocalypse Now,” has “a jolting effect,” said Ross, and makes us “think about the ways in which the darker side of the American genius employs its own art, a cult of popular art, to exercise its power.”

The reality of Wagner’s ugly political views means he can no longer be idealized, said Ross. Yet, “to equate him with Hitler ignores the complexity of his achievement and in the end does little more than grant Hitler a posthumous victory. The necessary ambivalence of Wagnerism today can play a constructive role: It can teach us to be generally more honest about the role that art plays in the world.

“In Wagner’s vicinity, we cannot claim to fantasies of the pure, autonomous work of art. We cannot forget how art unfolds in time and unravels in history. And so Wagner is liberated from the mystification of great art. He becomes something more unstable, perishable, and mutable. Incomplete in himself, he requires the most active and critical kind of listening.”

One audience member wondered how Ross can continue to enjoy the composer’s work in light of his anti-Semitism. Ross said he is haunted by the same question “every time I see Wagner.”

Whether it’s a “Heil” heard onstage or some particularly disturbing language in a libretto, all of Wagner’s operas contain a moment that “jolts me out of whatever kind of dreamlike immersion in the drama and the music I have achieved.”

Even so, while it may be a loss not to be able to experience Wagner today as a 19th-century listener did — with a “kind of total bewitchment” — current and future generations have a chance to approach the music with a deeper, more nuanced understanding, Ross said.

“I think this disturbing kind of intervention of reality and history might make for almost a deeper experience, certainly a more complex one. And so we shift from a kind of adoration and immersion to an experience that has this critical dimension to it. So we are always aware, we are always a little wary of Wagner. We should be.”