A different side of van Gogh

Photo by Ke Tang

With ‘Self-Portrait’ in Amsterdam, ‘Snow-Covered Field’ awaits Harvard Art Museums visitors

Don’t worry — he’ll be back.

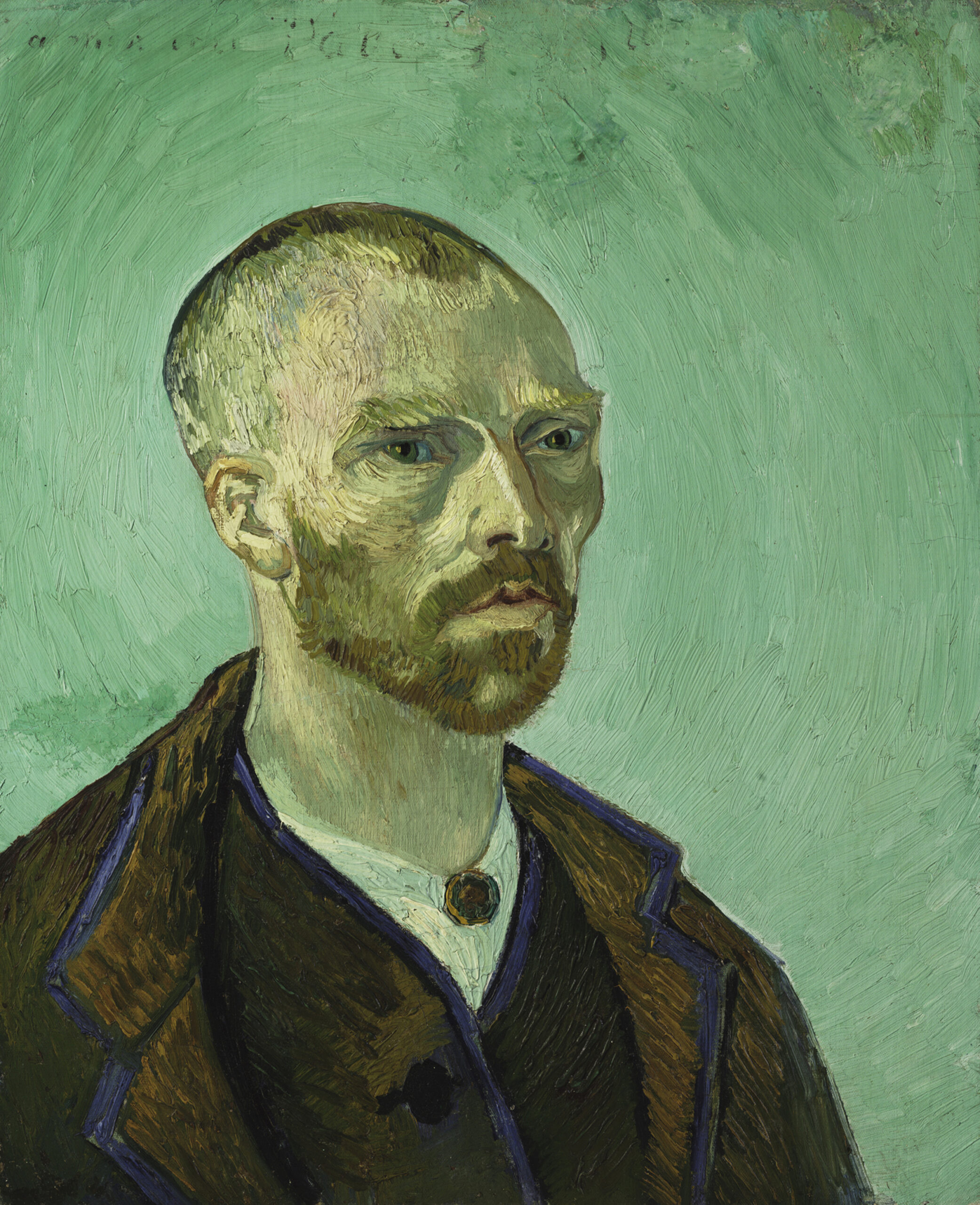

Vincent van Gogh’s “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin,” an image of the artist framed against a brilliant green background, one of the Harvard Art Museums’ most beloved works, is on loan to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam this spring and early summer.

In the interim, another Harvard treasure, a Picasso rarely on view due to light sensitivity, will fill its place in the ground-floor gallery dedicated to the collection of Maurice Wertheim, Class of 1906. “The Blind Man,” a 1903 watercolor, depicts an eyeless figure, his head tilted skyward. The haunting composition was created during the artist’s blue period, “in which images of impoverished men and women can be interpreted as allegorical representations of the five senses,” notes the accompanying text.

Still, museum officials didn’t want to take a van Gogh out of circulation even briefly without offering a striking substitute. Those who venture to the second-floor gallery, filled with works by masters such as Degas, Monet, and Sargent, will find a different gem by the troubled (and supremely gifted) Dutch artist, on loan from the Van Gogh Museum while the self-portrait is away.

“Snow-Covered Field with a Harrow (after Millet),” painted in 1890, depicts a stark, frosted landscape. In the foreground rests an abandoned plow and a harrow; a ruined tower stands in the distance. Van Gogh’s skill with the brush stirs a silent movement in the frame. In the painting’s upper left corner, a flock of birds, perhaps startled by an unseen passerby, rises to meet the sky. Lower, the landscape’s sharp strokes make the ground “look like it’s undulating or moving on its own,” according to Cassandra Albinson, Margaret S. Winthrop Curator of European Art, who helped facilitate the recent loans.

“Snow-Covered Field with a Harrow (after Millet),” Vincent van Gogh, 1890.

Courtesy Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Albinson’s eye is also drawn to the purple undertones captured in the white of the snow. “It’s something that struck me when I first saw it — that purple,” she said, noting that van Gogh was mimicking earlier impressionists known for infusing winter scenes with rich violet hues.

In deciding which work to choose from a selection of options offered by the Amsterdam museum, Albinson and other museum officials wanted something that could stand in contrast to their current van Gogh holdings as well as complement other material in Harvard’s collections. “Snow-Covered Field” was the perfect fit.

“We don’t have a pure landscape painting by van Gogh so this was something that was very special for us to briefly be able to exhibit,” said Albinson.

The painting will also be an important teaching tool. Van Gogh was inspired in his composition by “Winter (The Plain of Chailly),” an oil painting and series of pastels by the French artist Jean-François Millet dating to the 1860s. One of those pastels, part of the museums’ collections, is on display next to the loaned van Gogh.

“As a teaching museum, I was really interested in thinking about why van Gogh would have wanted to work from an image made by another artist,” said Albinson.

Image 1: “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin,” Vincent van Gogh, 1888; Image 2: ” The Blind Man,” Pablo Ruiz Picasso, 1903.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

Sadly, it seems part of the answer involves the artist’s inner demons. As a patient at a clinic in southern France, struggling to recover his health, van Gogh longed for inspiration, enlisting the help of his brother, Theo, who sent him a black-and-white print based on Millet’s earlier work. The etching sparked van Gogh’s imagination, leading to “Snow-Covered Field.” He referred to such efforts as “translating” a fellow artist’s work.

Van Gogh transformed Millet’s work “into something completely his own by accentuating the frozen furrows and the textured sky, changing the scale, and applying carefully chosen colors (some of which have now faded),” notes the display text.

But while van Gogh’s style is familiar to many, the meaning behind his work is often less clear. Perhaps it’s partly because he identified with Millet’s “position as a painter of rural scenes imbued with deeper meaning,” said Albinson. The curator hopes viewers will use their imaginations when interpreting the landscape, much as van Gogh did with his palette and brush.

“Van Gogh’s touch and personal attack on the canvas make you think about what he is trying to say and wonder why he goes to all that effort, especially here, to reinterpret another artist’s work,” said Albinson. “But I don’t think we need to feel any pressure to understand exactly what he is trying to say, and that’s one of the things that’s most interesting to me about his work. It evokes a very special feeling that in turn gives you a set of questions that it asks you to grapple with.”