The artist and her evolution

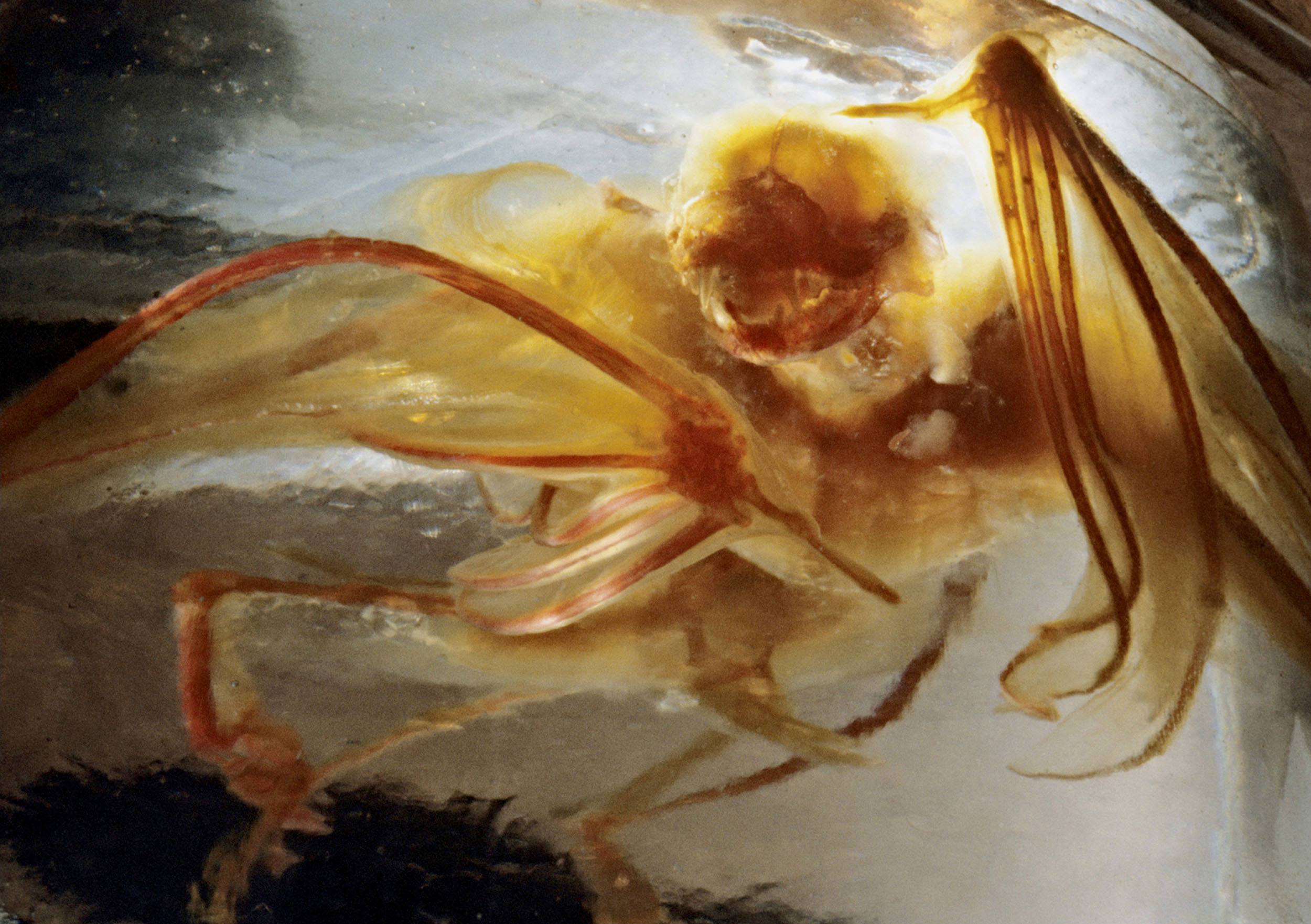

“The piranha in this jar comes from the Thayer Expedition to Brazil, a collecting foray led by Louis Agassiz, who made his students responsible for catching and preparing fish specimens,” Rosamond Purcell said. A label on a jar at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology says the fish was caught by the philosopher William James, she said.

Photos by Rosamond Purcell

Photographer Rosamond Purcell to talk about her long relationship with Harvard

The first thing Rosamond Purcell photographed at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology back in the 1980s was a pangolin, or scaly anteater, with “armor-like overlapping limpet shells and rapier claws.” The animal caught her eye because of its resemblance to a pinecone, so she placed a pinecone in the frame.

A seed was planted, and Purcell has since shot hundreds of photos at the MCZ alone — thousands more in her wide-ranging career. Purcell is speaking Thursday at 6 p.m. at the Harvard Museum of Natural History about the MCZ’s role in her evolution as an artist

Most of Purcell’s first photographs in the mid-70s were portraits of friends. Looking for a challenge, she wondered what would happen if she took photos of subjects she disliked or feared. Enter the MCZ. “I thought if I focused my lens on something that really gives me the creeps, I’d be getting somewhere.”

Her eye for the surreal poetry of decay and startling visual analogies has earned her acclaim. Her work has been displayed in science and art museums all over the world and recently she was the subject of a documentary, “An Art That Nature Makes.” She has written or illustrated some 20 books, three of which grew out of her 17-year collaboration with the late Harvard evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould.

“He gave a scientific legitimacy to things I was looking at as evocative images,” Purcell said, noting Gould often described their collaboration as “backwards.” Usually a scientist commissions an artist — “draw this or take a photo of that” — but Gould wrote text explaining the scientific principles underlying Purcell’s photographs.

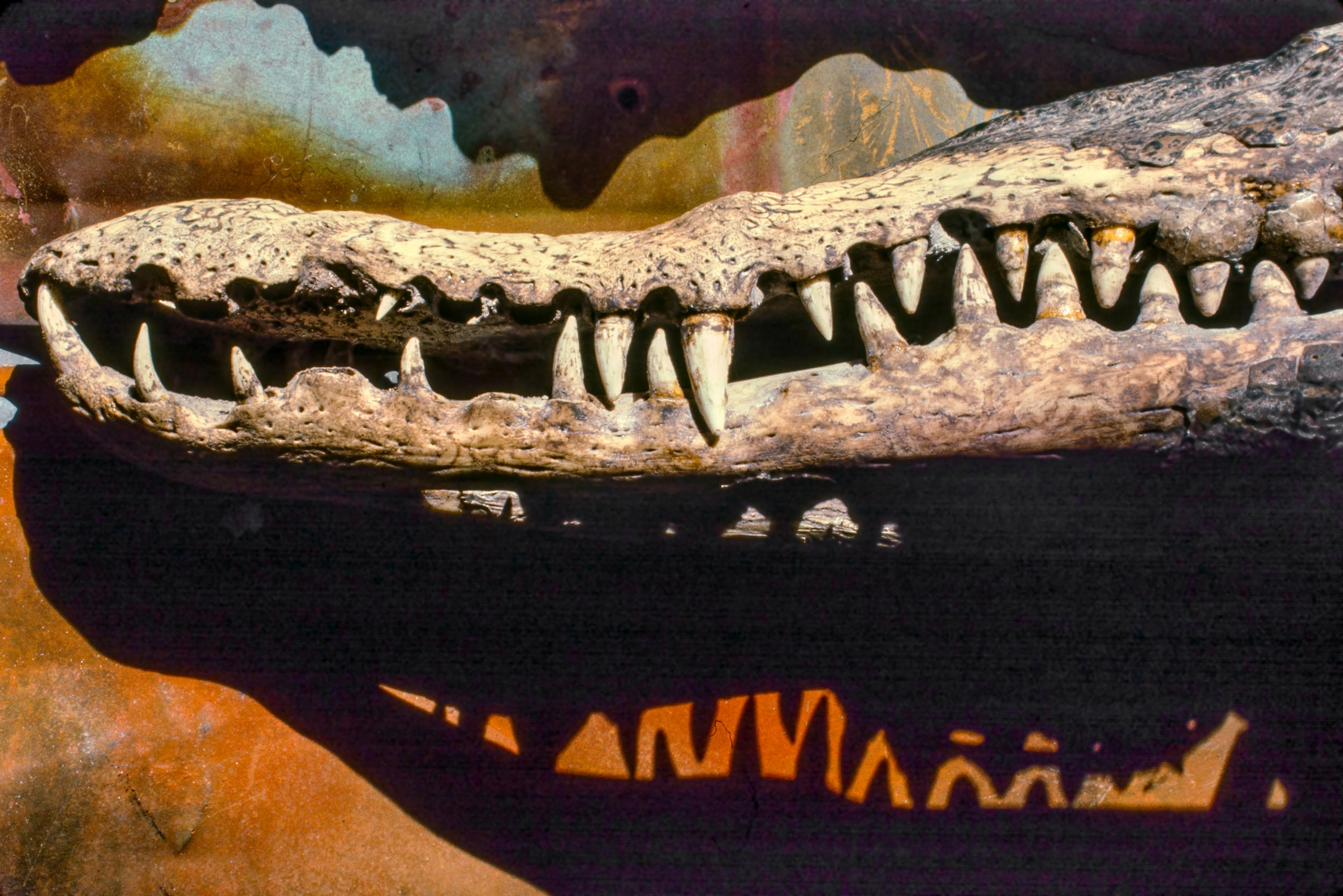

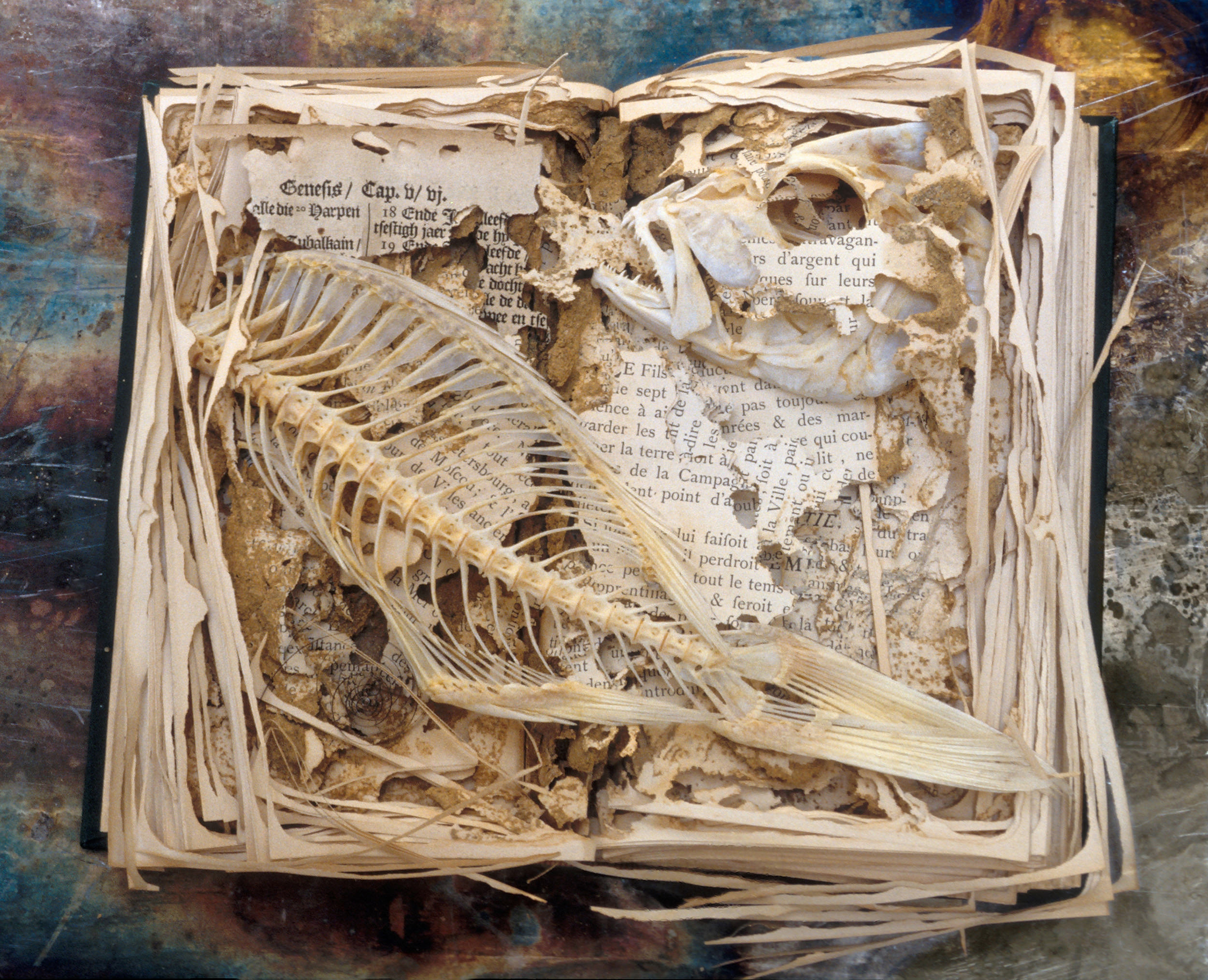

What follows is a small sample of Purcell’s photographs, many captured at the MCZ. Most are taken from her first book with Gould, “Illuminations: A Bestiary.” With one exception, the quotes that describe them are Purcell’s.

“The crocodile [below] does not stop growing until it dies of old age. In this photograph, the skull has been placed in the sun so that the shadow of its teeth lend an extended dimension to this portrait.”

“I originally went to the MCZ as a photographer in search of subject matter not easy to contemplate. This collection of monkeys [below] from the Mammal Department evoked a village under attack. From war, perhaps, or a meteorite.”

“The original termite-damaged book [below], found in a basement at Harvard, was on display when I visited the MCZ in the early 1980s. … I added the fish bones and a page from the Old Testament to evoke the idea of Genesis.”

“This ‘true toad’ [below], imported to eradicate pests in Australia, has no natural predator and became a pest itself. The swollen girth of this toad is magnified by the curvature of the jar of alcohol.”

“As Stephen Gould wrote of this image [below] ‘the soft baby, not yet ready for the rigors of life as a flying machine in a dense medium, retains a more “organic” look.’”

“This translucent, alizarin-stained chameleon [below] is no longer capable of camouflage. But the bone structure within its skin is now available for the scientist to analyze.”

“The skin of this well-preserved fossil [below] seemed like a flatfish caught yesterday, with the light glinting off its stone scales.”

“Here, arrayed like cartoon early worms poking their heads above the ground, we see dark spots at the wing-tips of Samia moths [below] facing each other in two rows.”

Stephen Jay Gould, “Illuminations: A Bestiary”

“This is a second example of a cleared and stained mammal [below]. Now submerged in glycerin, the bat seems to swim through a liquid ‘sky.’”