Emily Atkins (left) and Juliana Kuipers of Harvard University Archives were part of the team that curated “Harvard, 1968,” which is on exhibit at the Pusey Library.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

A year that changed students, and students changed the world

‘Harvard, 1968’ looks at the events that defined a decade

In any other year, the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. would have stood out as the tragedy that defined the troubles of its time. But in 1968, it was only the first — followed quickly by the signing of the Civil Rights Act and the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, and played out as anger at America’s involvement in Vietnam mounted — to shake, challenge, and change the country.

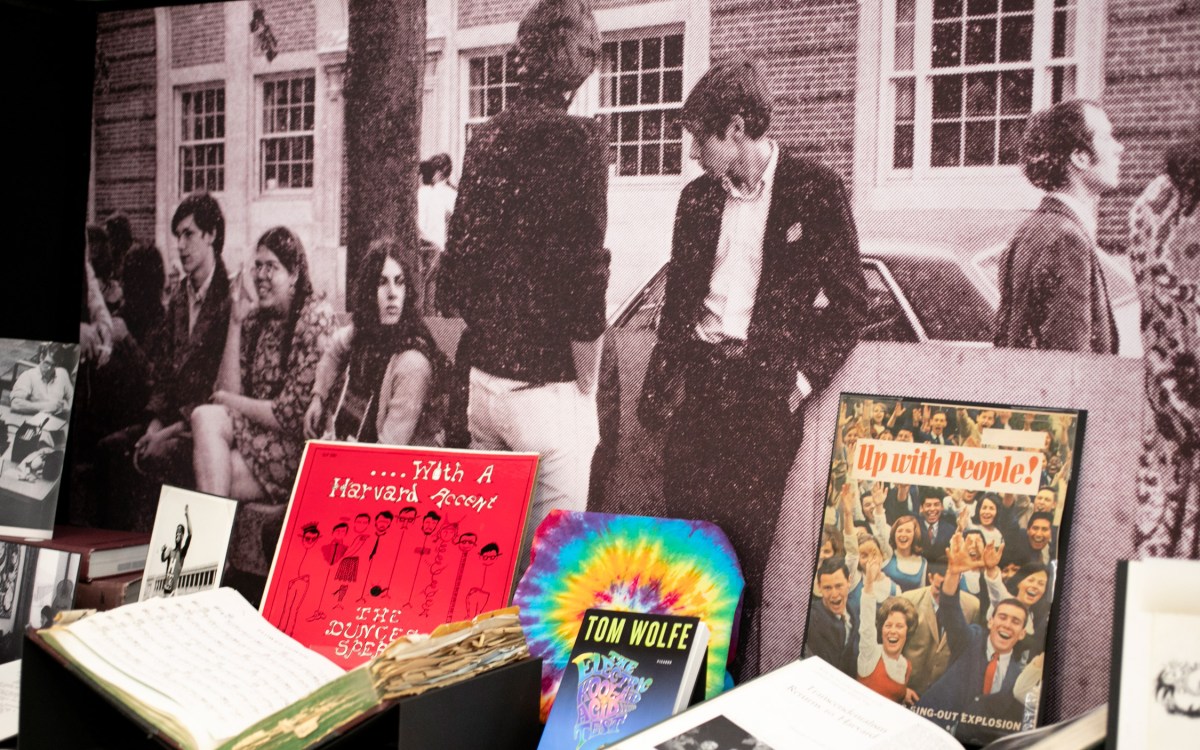

A new exhibit at the Pusey Library, “Harvard, 1968,” uses King’s death as a touchstone to explore what it meant to be a student experiencing, and helping shape, the political, cultural, and scientific revolutions that swept the world in that turbulent year.

These major historical markers live on in the photographs, letters, speeches, newspapers, posters, and a recording that document the upheaval on campus and put University events into a wider context. Also featured are views of others in the Harvard community, including some of the key faculty voices of the time.

“Harvard, 1968,” curated by Juliana Kuipers, Emily Atkins, Megan Sniffin-Marinoff, and Virginia Hunt of the Harvard University Archives, will be on view at the Pusey Library through June 14. It is free and open to the public weekdays 9 a.m.‒5 p.m.

MLK’s ties to Harvard

Martin Luther King Jr. spoke on campus several times, notably in January 1965 as a guest minister in the Memorial Church, and in 1962 at a Harvard Law School forum. Above, King greets guests with President Nathan M. Pusey after his 1965 sermon.

Photo courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Listen: MLK’s 1962 speech at Harvard Law School

Photos courtesy of Harvard University Archives

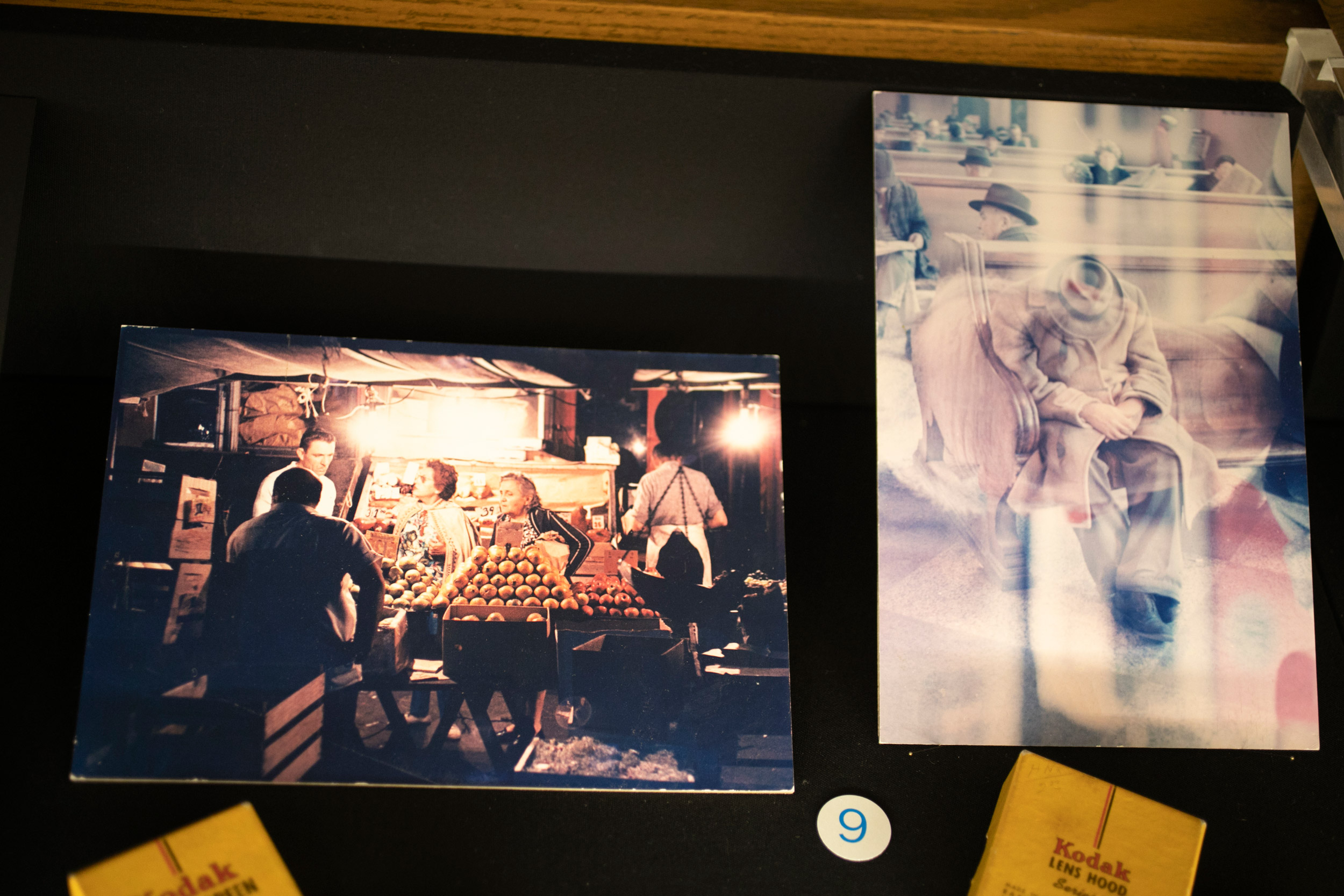

When King returned to Boston in April 1965 to lead a Civil Rights march from Roxbury to Boston Common, Ernest Singer ’41 was there with his camera.

Demand for change

Within days of King’s assassination, the Association of African and African-American Students placed an advertisement in The Harvard Crimson listing four demands that led to lasting change in the curriculum. The first course in African-American history, Social Sciences 5, “The Afro-American Experience,” was taught by Professor Frank Freidel in fall 1968.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Student protests erupt

At Harvard, the decade’s student protests reached a climax with the takeover of University Hall in April 1969, but there were several notable student demonstrations in previous years. U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s visit in November 1966 ended with Students for a Democratic Society demonstrators blocking his car, right.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

The war and the draft

The exhibit includes this Air Force Tactical Air Command fatigue jacket, circa 1968, worn by George Vernon ’67, who served during the Vietnam War.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

U.S. involvement in the conflict between North and South Vietnam sparked intense debate across this country, especially at the height of American participation in 1967 and 1968. Roger W. Sinnott ’66 took this photo of a march to mail letters to President Lyndon B. Johnson protesting U.S. action in Vietnam, Feb. 9, 1965.

Harvard biochemist Paul Doty was among those who urged Johnson to pull U.S. soldiers out of Vietnam. Above are notes he took in meetings at the White House on Sept. 30, 1967.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Tragedy strikes again

On June 5, just as the Class of 1968 was about to graduate, Robert F. Kennedy ’48, pictured here at a Harvard Board of Overseers meeting in 1963, was assassinated. Pusey issued a statement following the murder.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘A major science program for Harvard’

Plans for a new science program and center were announced at a 1967 press conference.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Paul Doty founded the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology that same year and was instrumental in recruiting scientists from various disciplines, some of whom undertook experiments that made genome mapping possible. One of Doty’s first recruits was James D. Watson, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, who had recently been awarded the Nobel Prize for physiology and medicine. Above, the Science Center takes shape in 1971.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Visual Studies launched

The year before the Class of 1968 arrived on campus, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts — the only building in North America designed by Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier — opened its doors, and the new Visual and Environmental Studies Program was launched. Above is a Le Corbusier sketch of the building, April 7, 1961.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

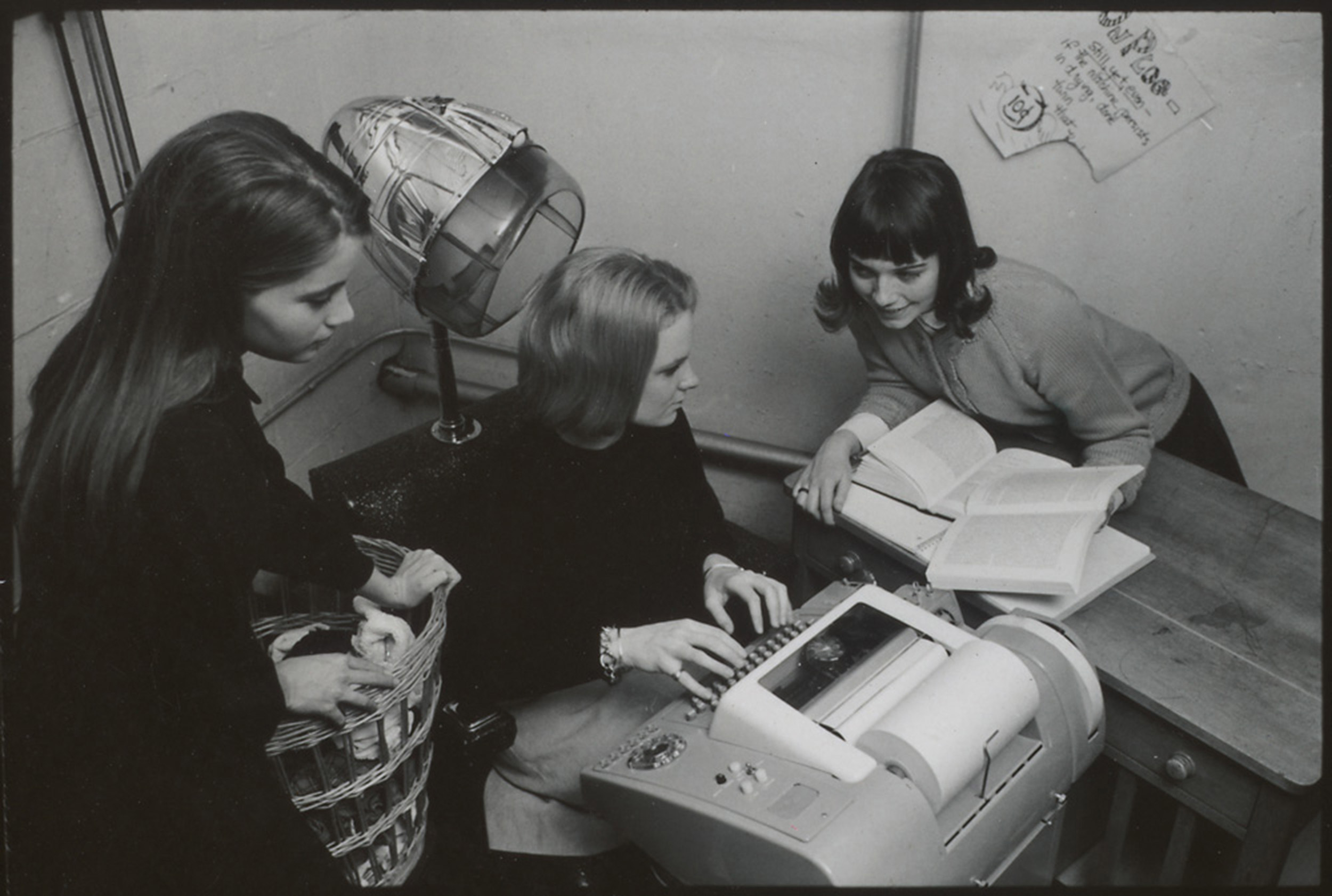

Early ‘personal computers’

In 1962, two years before the Class of 1968 arrived, Harvard opened the Computation Center, built at the corner of Oxford and Jarvis streets, replacing the old statistical laboratory.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

By the mid-1960s, demand for computer time for students doubled and the University placed smaller “personal computer stations” at other campus locations. Here, Radcliffe College students circle a keyboard in the basement of Cabot Hall in 1966.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

‘A generation in search of a future’

“All of you know that in the last couple of years there has been student unrest, breaking at times into violence, in many parts of the world. … Unless we are to assume that students have gone crazy all over the world, or that they have just decided that it’s the thing to do, it must have some common meaning.”

George Wald

On March 4, 1969, a Harvard professor gave a talk that went “viral.” Nobel Prize-winning biologist George David Wald’s speech at an anti-war teach-in at MIT was reprinted in newspapers and magazines and released on an LP. Artist Mary Cady Johnson created a series of silk-screened prints of Wald’s speech.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer