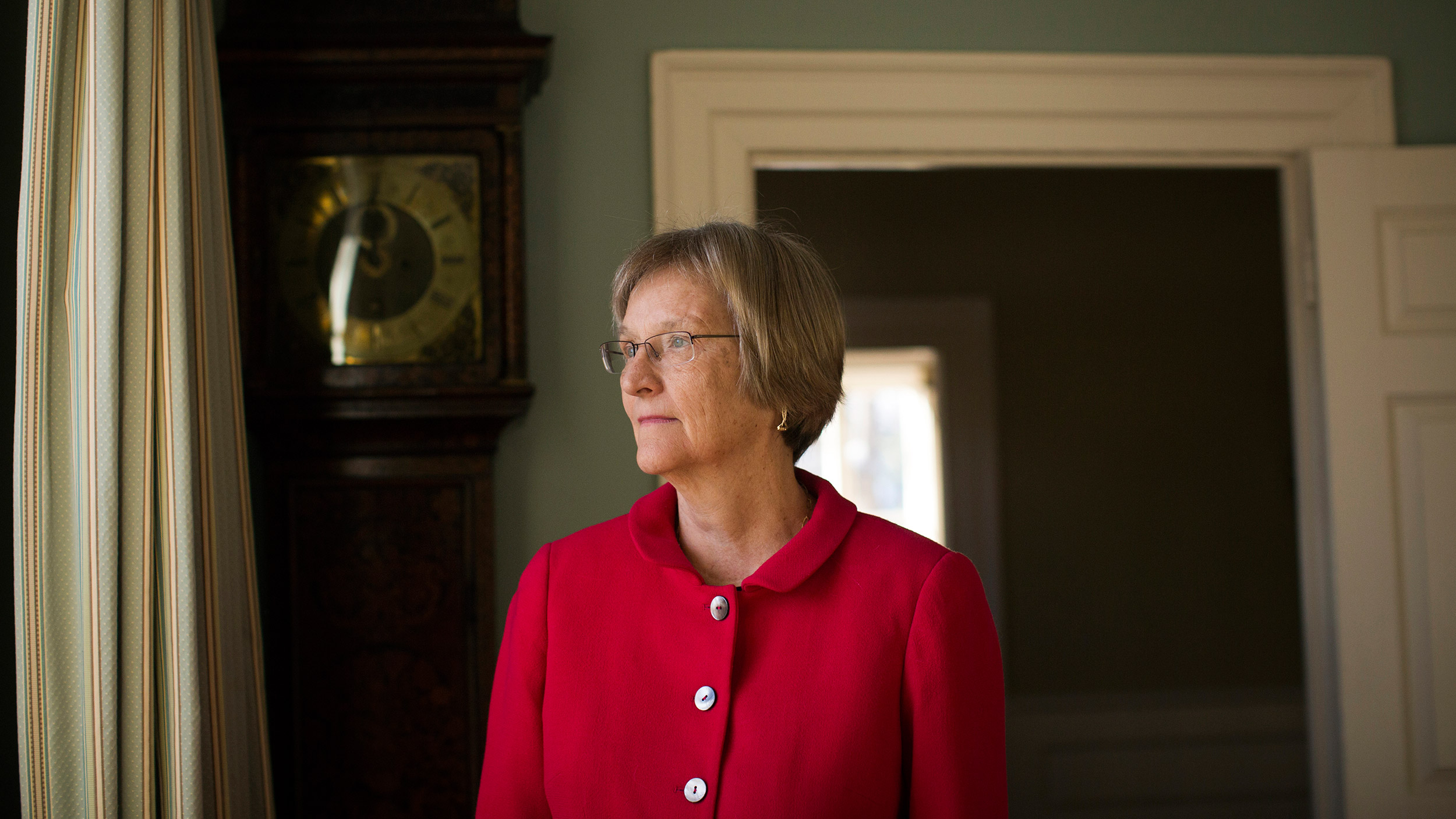

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘What the hell — why don’t I just go to Harvard and turn my life upside down?’

Family, history, and the 1960s all helped to shape Drew Faust, but it was illness that urged her forward

The setting of her childhood — Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley — instilled in Drew Faust a dual passion for history and justice.

Weekend trips to battlefields and joining her brothers to play soldier helped to deepen her interest in the Civil War. Decades later, her study of the conflict’s devastating toll in blood and grief, “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War” (2008), was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

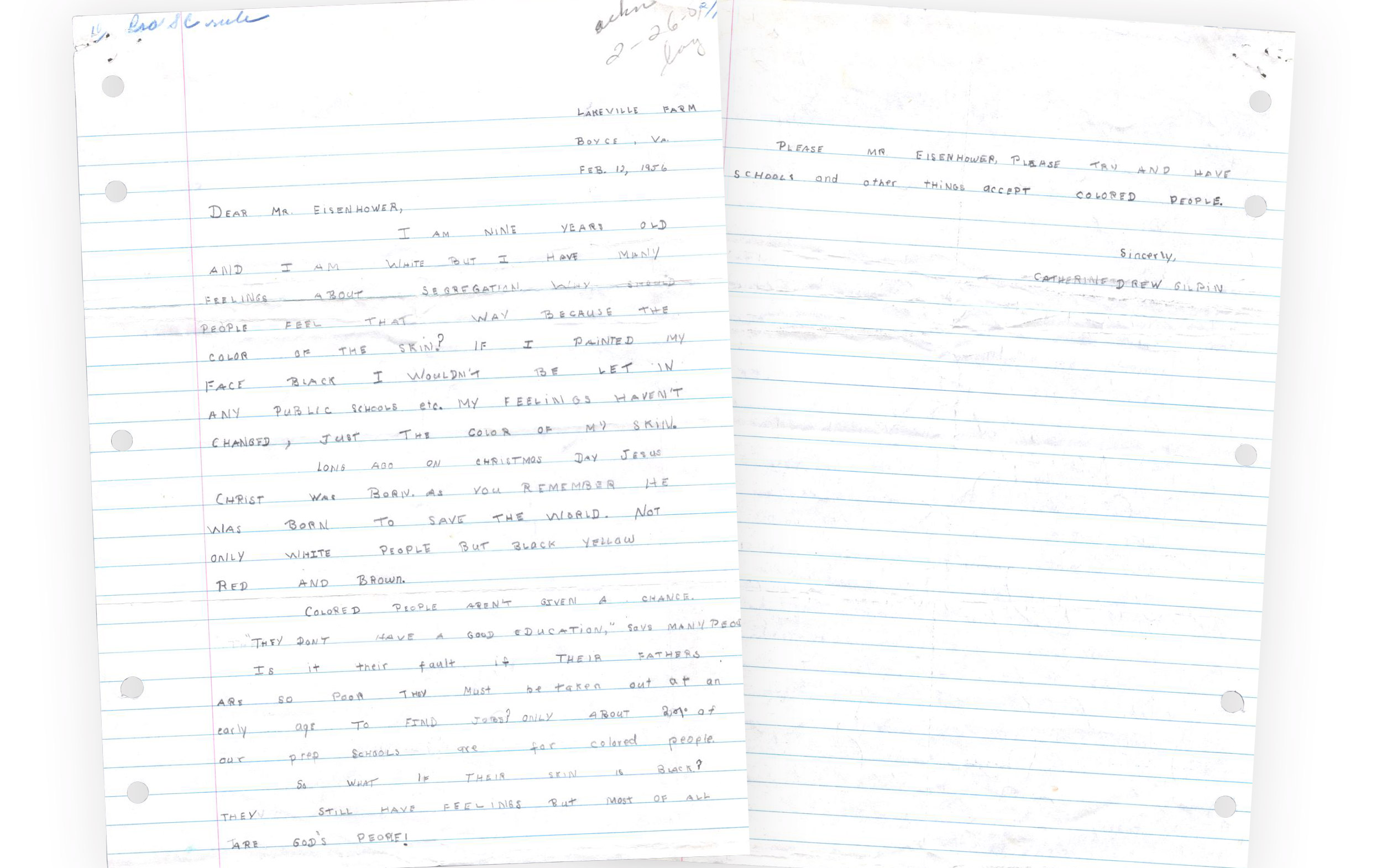

The inequality she saw in the world drove Faust’s early devotion to civil rights. At age 9, she penned a letter to President Dwight D. Eisenhower urging him to support integration. As a freshman at Bryn Mawr, inspired in part by Freedom Rider John Lewis, she skipped a midterm to march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala.

Faust was a member of the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania for 25 years before her appointment, in 2001, as founding dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Six years later she became the first woman to lead Harvard University, or, as she said at the time, “I’m not the woman president of Harvard, I’m the president of Harvard.” She will step down on July 1.

You grew up in the Shenandoah Valley. I’d love to hear a little bit about that and what your early life was like.

I grew up on a farm. My father was in the horse business, so I was always surrounded by animals. I rode a pony, had sheep in the basement, little lambs that we saved when their mothers died in the winter, and ducks, chickens, rabbits, dogs, cats, everything you can imagine. When I was in, I guess, seventh grade, I got very interested in joining the 4-H Club and in animal husbandry. So I raised a steer both my seventh- and eighth-grade years. The first one was named Toby, after Sir Toby Belch in “Twelfth Night,” and the second was named Ferdinand, after the book about Ferdinand the bull who sits down and smells the flowers.

I’d get up every morning before school, go feed them, and groom them in the afternoon. And I’d go to the 4-H meetings. I was the only girl interested in animal husbandry, all the other girls were doing sewing and canning and those kinds of things. I was always kind of a tomboy.

You’ve described yourself as a rebellious daughter who clashed with your mother. What were those clashes about?

A lot of them were about clothes, because I guess clothes make the woman, she would have thought. She was always trying to put me in what she regarded as appropriate clothing. There’s a portrait of me painted when I was 4. I remember coming home from school and being put in this little pink organdy dress that itched. The sleeves were tight. I hated it, and I didn’t want to sit still. It always seemed to me that boys’ clothes were much more comfortable and adapted to what I wanted to do, which was run around and go feed the steer or whatever.

My mother’s desire to have me be a proper lady came up against constant resistance on my part. And then there were things like what my three brothers were allowed to do compared to what I was allowed to do. You could get a driver’s license when you were 15 in Virginia. So my mother established a rule that I wasn’t allowed to drive with the boys at night. I don’t know what she thought I’d be up to, whether it was she thought I’d be killed because they were crazy drivers or we’d be up to no good. I don’t know. But that infuriated me. Why was there that rule that applied to me and not to them? There were some rules about gender that I’m describing. But there were also these rules about race that I could never understand, and they seemed to me preposterous.

We had a cook who worked for us named Victoria who was wonderful and a man named Raphael who just did everything — drove us to school; did errands for my father; everything you can imagine around the house; fixed things. We were very attached to him. He was very funny and very attentive to the kids.

There was a bathroom off the kitchen that Raphael and Victoria used, and we were told not to use it. We had a segregated bathroom in our house. I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t use that bathroom if that was the nearest one. It all seemed very odd to me. It was explained to us that it was their bathroom and you shouldn’t be intruding on their privacy. And I’d say to my mother: “They don’t care. Why do you care?”

You wrote a letter to President Eisenhower when you were 9 urging him to support integration. Does it strike you now, looking back, that you had such a strong opinion about right and wrong at such an early age?

I would explain it as a product of being a pretty intellectual, rational kid and being told one set of values in Sunday school and at school about what America was, and then seeing just enormous contradictions with what was going on in the world around me. There’s a way in which the clear-eyed sight of a child doesn’t have the nuance to erase contradictions. It seems very stark. And I think it just seemed stark and contradictory to me. I was pretty outspoken on stuff. And I think maybe having to struggle for my own rights as a little girl made me think, “Who else is being excluded or treated unfairly?”

“I am nine years old and I am white but I have many feelings about segregation,” Faust wrote to then-President Eisenhower.

Courtesy of the Eisenhower Library

You talk about being intellectual from a young age. Did that come from one parent or the other, or both?

My father graduated from Princeton and was, I think, really smart. And my grandmother, his mother, who lived near us, was really smart and read a lot. Daddy was not intellectual. He read trashy books, but he was always very amusing and verbal and smart. My mother never graduated from high school. I think she was dyslexic. Two of my brothers are dyslexic. One’s a lawyer and the other has a Ph.D. in geology, so they’ve overcome it. But they had to have a lot of attention in school.

My mother was led by emotion, not reason. That’s why I fought with her all the time, because I’d come up with these syllogisms of this is true, that’s true, therefore it is true that I should be allowed to do X. And she’d look at me and blow up and say, “I don’t care. Argue away. You’re going to do it because I said you are.”

Was there one critical thing you took from each of your parents?

I did take things from both of them. There are all these sayings my father had that I impose on everybody around Massachusetts Hall all the time, some of which I think are quite wise, such as that there’s no excuse for being lousy. In other words, treat people decently. There’s never an excuse for mistreating somebody. I think that’s a pretty good saying.

And another one was, “Any one you walk away from is a good one.” He used to say after family occasions, when there were 24 people at Christmas lunch, and everybody had a beef with everybody else, you know, the whole normal family holiday thing — whose politics, whose resentments are going to come out over this meal? — when we’d get in the car and go home, he’d say, “Any one you walk away from is a good one.”

After he died, I wondered where this came from. So I typed it into Google and I learned it was an aphorism used by pilots in the early years of aviation who crashed their planes all the time. So, of course, any one you walk away from is a good one.

“My mother’s desire to have me be a proper lady came up against constant resistance on my part.”

What about your mother? It sounds like your relationship could be challenging.

Yes, she was very intensely moral and moralistic — not to say judgmental about things. So she was pretty powerful in her insistence on things.

What do you think your mother would have thought of you becoming the president of Harvard?

It’s just unimaginable to me. She died in 1966, when I was a junior in college. I don’t know what she expected me to grow up to be, certainly not president of Harvard. She was never very academically engaged. She always found it kind of puzzling and bewildering that I was a good student and loved school, so I think the whole academic dimension to my career would have been very startling to her, much less the Harvard president part.

Faust is installed as Harvard’s 28th president in 2007.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

I was surprised to learn you were so young when you left Virginia. I think it was at 12 or 13 that you enrolled at Concord Academy — is that right?

I was a year ahead of myself in school. I finished eighth grade when I was 12. It was in a little private school in Virginia. Most of the kids at that time went away to boarding school. It was also a time when the public schools in Virginia were closing instead of integrating, and there were a lot of lawsuits. So we did this tour of private schools. I looked at St. Timothy’s in Maryland and Milton and Concord and others. I just fell in love with Concord. It seemed very not full of itself, just sort of rational and more open than a lot of schools. It was, to use a word that gets overused, transformational for me to be taken seriously as a girl who loved intellectual things and to be in a community where there were a lot of strong women. It was an all-girls school at that time.

Concord was really important for me in so many ways. One of them was a kind of growing and broadening of my political consciousness. In the summer before my senior year, I went on this trip to Eastern Europe. I visited East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia. We were a group of about 10. Three of the members of the group were African-American. I had never been close with African-Americans before who weren’t Victoria or Raphael. One of these young women was someone who had been one of the first to desegregate schools in Atlanta. One was a co-leader of the group, the brother of Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot and the father of Kimiko Matsuda-Lawrence, who created I, Too, Am Harvard.

It was just an introduction to the inside view of what was changing in race in America that spoke to me. Concord made me open to it and aware of it. That summer, thinking about what freedom is behind the Iron Curtain, with a group of Americans who also were thinking about what is freedom, what is justice — that had a huge impact on me, and I think established the context for my outlook, my politics, since that time.

The next summer, the person who ran these trips decided he was going to do one into the South. So I spent the summer of 1964 with a group of young people in civil rights hotspots in the South. We were in Orangeburg, we were in Birmingham, we were in Prince Edward County.

What was that like?

It was pretty extraordinary. The point was to try to reach across difference. I remember a meeting we had with town officials in Farmville, Virginia, a town that had closed the public schools for six years rather than integrate them. We asked them why they’d done that, why they felt as they did about race, and we heard very directly the racist logic that undergirded segregation — the idea of inferiority. We were sitting there with African-Americans in the group. We stayed in Orangeburg with families. The family I stayed with had a 9-year-old who had been arrested 10 times for being active in the civil rights movement.

While we were in Orangeburg, I was walking with an African-American from our group, and we got chased by a carload of white segregationists who were throwing things at us. Just as we were starting that work, the civil rights workers Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney disappeared in Mississippi and were found dead later that summer. That summer we also spent time in Birmingham on what was called Dynamite Hill because white segregationists threw bombs at it trying to blow up the houses. It was a kind of upper-middle-class enclave. It’s the area Angela Davis came from. Her family was there. Successful African-Americans seemed to segregationists the most threatening to the whole notion of racial inequality. So that was a powerful summer.

And it sounds like Bryn Mawr was a powerful experience?

It’s interesting when I think about why I chose Bryn Mawr. A number of my classmates went to Radcliffe. Looking back, I had no interest in going to Radcliffe.

Why?

I think it was a much healthier environment for women at Bryn Mawr than being a second-class citizen at Harvard, which is what I would have been had I gone to Radcliffe at that time. That was still the era when I wouldn’t have been allowed in Lamont Library. All of the faculty that taught me would have been male. At Bryn Mawr, there were male faculty, but there were a lot of very strong, accomplished women on the faculty. Of course, women were in leadership positions and ran the place. So it was a very different environment from what I would have encountered if I were a few years younger and had gone to Princeton or Yale. It would have been a very different experience. So I was in a kind of country of women at Bryn Mawr.

“I think it was a much healthier environment for women at Bryn Mawr than being a second-class citizen at Harvard, which is what I would have been had I gone to Radcliffe at that time.”

My first year there I was still very much in the mindset from that summer being in the South and less interested in my schoolwork. In letters to a friend that I recently found I questioned being in school when the world was erupting. So I became very active in a variety of political causes, including the then-version of Students for a Democratic Society, which had not become the kind super-radical organization it later did. Then it was a grass-roots democracy organization. We worked with communities in Philadelphia. I worked on rat-control projects and I spent a lot of time on weekends, and other times, too, in the city. I was much more engaged with that than I was with my schoolwork.

Was that the year you skipped an exam to protest in Alabama?

Yes. When the spring rolled around people in Selma were being battered, including John Lewis, and I saw it on television and I knew I had to go. I persuaded my then-boyfriend, whom I’d worked with on the rat-control project, that we needed to go to Selma. We borrowed his roommate’s car and I told my sociology professor, Mr. Schneider, that I was going to cut the midterm because I was going to Selma. He was really concerned. I was 17 years old, and he asked me if I was telling my parents. I said no. So he said, “I want you to call me every 24 hours, and if I don’t hear from you, I’m going to do something.”

So off we went. We alternated driving 100 miles at a time and we arrived in Atlanta exhausted. I knew my way around a little bit from being there the previous summer, so I took us to Morehouse College, where we parked in their parking lot to sleep in our car. (You also had to be worried, then, that you were traveling around with a guy you weren’t married to. That was as big a deal as any of the rest of it.) While we were there a guard came up and knocked on the door, and we thought, “Oh Lord.” We rolled down the window and told him we were on our way to Selma, and he said, “Bless you,” and kept going.

We got to Selma the next day, parked our car, and walked toward the Brown Chapel, where the pre-march gathering was taking place. Halfway there we wondered if we might be killed on this adventure. But we had heard that Lyndon Johnson had nationalized the Alabama National Guard, so that meant there was going to be some law and order. As we were walking from the car to the chapel, we saw these two Alabama National Guardsmen coming toward us. We thought, “Oh, they’re here to protect us.” But as we walked by one of them just hauled back and slugged me in the chest.

What?

Yes, and then he just kept walking. I think we marched maybe nine miles that day. We spent the night with a local family who took us in, as many families were doing for the marchers.

You worked for HUD after you graduated from Bryn Mawr. Did your activism in school inform that choice?

Yes. By that time, there had been all the urban rioting. King had been killed the spring of my senior year; cities went up in flames. So a lot of the attention to issues of race and justice in the United States had shifted from the South. King took them more north, and began calling for more economic justice. He was not a popular man at the time he died. He was not seen as a hero; he was seen as antiwar and too left. The North was pretty happy about justice in the South, but not so happy with attacks on discriminatory housing policies and segregation and so forth in the North.

So the whole possibility of the clear-eyed moral cause that the early civil rights movement had represented — or the early ’60s and mid-’60s represented — evaporated in the conflicts of 1968. In the time between my freshman year and my senior year, I got very involved with anti-Vietnam campaigns: marches on Washington, working with an organization called Vietnam Summer in the summer of 1967, going door to door to talk to people.

I also got involved with something called the Committee of Responsibility (COR), an organization that was set up mostly by doctors who practiced at Temple University who were concerned about children being disfigured in Vietnam by napalm. The group raised money to bring kids to the United States for plastic surgery and rehabilitation. I think they also thought that if these children were brought to the United States and more people were made aware of what was happening in Vietnam, it would be an antiwar effort as well.

So I was active with them, I raised money with them, I gave talks with them. I did a lot of photography when I was a junior and senior in college and together with a psychiatrist at Temple, whom I had met through COR, we proposed this project for North Philadelphia of getting kids in the community Polaroid cameras and having them photograph their communities and use that as a way into mental health issues in the North Philadelphia community. I applied for a grant together with him. It wasn’t funded, so I didn’t get to do that.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

What inspired your turn from HUD back to academia?

I found much of working in the federal bureaucracy frustrating. I also missed being in universities, colleges, where people could speak their minds. I arrived at HUD in the summer of ’68, when everything was being directed toward getting Hubert Humphrey elected, and then he wasn’t. So there was this political shift. For a political naïf, it was an introduction to the realms of politics. I ended up being asked a lot at HUD to write, because people thought I wrote well.

You earned honors in history at Bryn Mawr, and hold advanced degrees in American civilization from Penn. I’m really interested in understanding where your passion for history came from.

Oh, my passion for history — it was so overdetermined, because when I was a kid we used to go to the Civil War battlefields on weekends. My brother collected Civil War armaments. We played Civil War in the woods around the house. History was so present in everything.

Can you expand on that a little bit? What was it about those childhood experiences that so struck you that you chose to carry them with you into your professional life?

I’d say it’s a pervasive sense of the presence of the past. This is almost a cliché in Southern history, in Southern literature, but I do think it’s a characteristic of the South, the places inhabited, as Faulkner said, by “defeated grandfathers and freed slaves” [“Absalom, Absalom!”]. It’s just that those realities of the war and its memory, and the legacy and the terrible stain of slavery, are omnipresent. It is a force in how people live their own lives in the present, and that’s evident.

Let’s turn to your writing, in particular “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the Civil War.” I’d love to know how you came to that specific topic.

Two things. I entered Civil War studies as a practicing Civil War historian at a time when U.S. history was changing dramatically. It was moving from a focus on generals, politicians, battles, and war to much more attention on everyday life and social history and the experience of people other than the powerful.

So there was this whole shift in emphasis that transformed the historiography of the Civil War, beginning probably in the early ’80s, and I very much benefited from that wave, because it opened up so many other dimensions of the experience of war that hadn’t been really treated adequately before. So that was one thing. I had been trained to think about what was people’s experience, rather than who made what happen on a policy, political, or military level.

There was also a personal dimension to it. I was diagnosed in the summer of 1988 with breast cancer. I was 40 years old, and it was this stunning news from a mammogram. I had a mastectomy and was just shocked and kept thinking: What is health? What is sickness? What is life? What is death? It had a big impact on me.

Afterwards, I wanted to work with breast cancer patients, and I did so through an organization called Reach To Recovery, where newly diagnosed breast cancer patients connect with breast cancer survivors. I wanted to do it partly because I wanted not to forget what that experience of looking at death had been like when I had my mastectomy — when I was diagnosed. Because I think it so sharpens your perceptions and makes you smell the flowers, makes you re-prioritize, makes little perturbations of life seem irrelevant. And that was very valuable.

Also, I kept reading about these 19th-century Americans, and I reported in my lectures in class on this enormous death toll. The fundamental experience for these people was death — either the threat of it or the reality of it; the proximity of it. No historian had talked about this. And as I started reading more about it, I came to see that this notion of living a life in which the awareness of death is ever-present is an enrichment of life rather than a diminution of life. In the 20th century, there’s a lot of literature about our denial of death, our refusal to confront death, our resistance to talking about it. And I could see some of the dimensions of what my experience had brought reflected in how 19th-century Americans thought about the good death and how important it was to think about death.

“I wanted not to forget what that experience of looking at death had been like when I had my mastectomy.”

But as I embarked on the project, I just found more and more astonishing things that I had not been aware of. No one ever notified a soldier’s family when he died. There were no dog tags, so there were all these people who were unidentified. So it was just unfolding — this panoply of information and insight that was, I think, never addressed before because it was so obvious that no one ever thought to.

That’s the historian’s dream, right, to be able to look at existing material and come up with something new and different? Did you know that you were onto something that would resonate?

Yes, it became evident to me that this was a really important subject. I was asked to give an honorific lecture — the Fortenbaugh Lecture, which is presented by a historian every year at Gettysburg at the anniversary of the Gettysburg Address. I tried out the death idea there, and people were just so responsive. So I started working away at it, but then along came Radcliffe, and that delayed it a lot. But I was just determined I was going to finish this.

You were at Penn for 25 years as a member of the faculty. What inspired you to consider switching to an administrative role for the Radcliffe job?

I was asked often to do administrative things at Penn. I was part of this first wave of substantial numbers of women as institutions began to think about placing women in leadership positions and responding to the needs of their female students. So I was asked to consider administrative posts quite a lot, and I always felt I wanted to stay with my scholarship and in my classroom, so I resisted it.

Still, as I got further along in my career, I was constantly being asked to do administrative things — run a committee, be vice president of the American Historical Association, run a big committee for [Penn President] Sheldon Hackney. At Penn I was on a committee that ended up being called the Faust Committee, which I objected to strenuously. It was a committee focused on the university community and on inclusion and belonging. Do you know the Penn campus at all?

No, not really.

There’s this kind of central artery of the campus that used to be a street and was turned into a pedestrian thoroughfare called Locust Walk. One of the issues we faced was that all the Penn fraternities were along Locust Walk, so the campus’s central artery was dominated by these organizations. Guys would sit out in front and comment on all the women when they walked by. So one of the commitments of this committee was to diversify Locust Walk and move a number of the fraternities off of it and to put a women’s center there. Sounds familiar, right?

Yes.

So I was constantly being asked to do all this, and I thought, I need to get my head on straight and either say no to more of this or really take on an administrative job and do it as my day job and say: I’m committing myself to this. I’m not just going to try to do it on top of everything else.

Around that time, [Harvard President] Neil Rudenstine called me and said they had just merged Radcliffe and Harvard and that this new organization was being set up. He was seeking suggestions for what the institute ought to look like and who should be dean. I’d been around the block a couple times. I knew that I was on his list. So we had a conversation. Then he came to Philadelphia and we met and had another good conversation. Then he called me again, maybe late November. In January, he called again. He said, “You may know that I’ve been calling you because I’m really interested in having you be a candidate for this position.” I told him I was never leaving Penn, and that I was never going to be an administrator. He said, “Well, if you have as much as a 1 percent interest, would you just keep talking to me?”

That’s a good line.

I used that on [current Harvard provost] Alan Garber — the exact same line. It worked too. So we kept talking. He asked me to come up and meet with the committee, and I really didn’t think I was going to do it. I said to Charles, “How would you feel if I said I wanted us to move to Massachusetts?” [Faust married Charles Rosenberg, a historian of medicine, in 1980.] He just didn’t take it seriously, because I’d said no to all these other opportunities over the years.

You had turned down Harvard before. Why?

The history department was really a mess. They had been unable to appoint anyone in U.S. history for well over a decade. I felt if I came here, I would have to spend my time helping to clean it up, and I had a really nice, happy situation in Philadelphia.

Then, come mid-March 2000, I said yes to Neil, much to my astonishment. I think cancer played a role in this decision as well. In January 1999, if I get my dates right, I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer, and I had a thyroidectomy. I remember thinking to myself very explicitly through all these conversations: If there’s going to be risk in my life, why don’t I take some risks instead of having these risks imposed on me?

I think that having the second cancer made me think, What the hell — why don’t I just go to Harvard and turn my life upside down? Which I don’t think I would have done, necessarily, without that. It also meant I didn’t have to disrupt my daughter because she was going to college anyway. That made it easier. And then there’s a third part of it, which is that Neil assured me that because it was an institute for advanced study, I would be able to have time to devote to my death project, to my work. It didn’t turn out that I had as much time as he had anticipated, but it was like easing into administration, in the sense that it seemed like I could retain a scholarly identity with it.

It sounded like it was a challenging time, and that there was a lot of reorganizing and cuts that needed to happen.

I think Neil may have quite consciously chosen an outsider.

When you say an outsider, not someone who had graduated from Harvard?

Not someone who had gone to Radcliffe, not someone who’d been embedded in the wars. He had described to me the cannon shots up and down Garden Street, between Radcliffe and Harvard. Relations were very difficult. The merger was pulled off through enormous effort and against the wishes of many. I think there were 30,000 Radcliffe alums, and 20,000 of them were irate, but none of them could blame me. I was like an innocent who marched in and said let’s move to the future.

So I had all the irate alums to deal with, but then I also had an organization that was ill-suited for what it was supposed to be. It was supposed to become an institute for advanced study, but it had this vestigial structure, staff, identity, that needed to be changed. So I had an early conversation with Neil about where I would get my legitimacy. I’m this person from Penn. You’ve appointed me. Do I just order everybody to do everything?

Together, we decided that I would get a group of distinguished people to come and be an ad hoc advisory committee to help explore how the new Radcliffe should be structured. It was indeed a distinguished group and included the then-heads of the Princeton Institute, the National Humanities Center, the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, so the three most prominent organizations for advanced study. Caroline Bynum, a very respected university professor at Columbia, a Harvard alum, and advocate for women, was the chair. A scientist who is very well respected at Princeton named Shirley Tilghman was on it. She was not yet president. So I got to know her then.

This committee was my cover and my advisers. I was named in March. I didn’t take office until the following January [2001]. From June on, the committee started working and they were invaluable. So that was a kind of context that helped me build the constituency for a lot of these efforts.

Another thing that helped me was that over the preceding six or eight years, Harvard had recruited many women from Penn to the faculty. So there was this whole slew of women that I knew on the Harvard faculty: Claudia Goldin, Elisa New, Lani Guinier, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Irene Winter. So I had a lot of friends who helped me translate Penn to Harvard.

At Radcliffe and as Harvard president, how did you balance all your professional responsibilities with being a mother?

When Jessica was little, and really through high school, I was a faculty member, and that gave me a lot of flexibility about how I used my time. I didn’t have to sit in an office from 7 in the morning until 7 at night. I was expected to produce research and scholarship, but a lot of that I could do in the middle of the night or on weekends. So my time was more flexible. I could show up at her endless athletic events, which I loved doing, or go to a student-teacher conference, or stay home with her when she was sick. My husband, as you know, was also an academic, so between us, we outnumbered her — that helped. And we could adjust our time. I can’t imagine how I would have done this job with young children. It just seems impossible to contemplate, partly because it would have been so frustrating to be torn between spending time with children and doing the myriad of things that a president needs to do.

How do you separate out your private life? It must be challenging to have so many demands on your time and a job that is so outward facing.

I can’t imagine doing this job at an earlier stage of my life, when I had a child at home. I would have had to have been much more aggressive about setting boundaries and so forth. There are not clear lines between the private and the public life in this job. You’re always president of Harvard. Any moment you can get a phone call. Any moment you can get a tweet or a text that something’s going on.

We have a place on the Cape, and I would say we escaped there. A big division in my life is when I’m performing as president of Harvard and when I’m not performing the role of president of Harvard — when I’m going to the dump on Cape Cod. I love it. I’m heaving the bags of garbage into the garbage bin, and nobody knows or cares who I am.

But even on a Sunday, when we’re walking around Fresh Pond, people recognize me. They don’t necessarily come up to me then. I’ll meet them at some event at Harvard, and they’ll say, “I see you all the time walking around Fresh Pond.” So you are the president of Harvard all the time.

How has your husband helped you navigate that?

He’s been amazing. I didn’t know what his reaction to this would be or how he’d want to be part of it or not. I anticipated that there’d be so many things he wouldn’t want to be part of and that he would kind of keep his life very separate. He’s embraced it. He’s participated in just about everything. He really, I think, enjoys it.

And it must be nice to have someone who understands and knows Harvard, too.

He’s hugely supportive. The hardest thing is that he can be very protective. He always wakes up incredibly early, often at four in the morning. So I’ll come stumbling downstairs and The Boston Globe will be there, and he’s been waiting for two hours to say, “What is this about? How dare they say this about you! Who’s going to slay this dragon?” And I’ll read it, and I’ll go, “Oh, that’s nothing,” or “People say that stuff.” He can get much more excited than I do about things that are hostile to me.

You’ve said knowing that Celtics great Bill Russell struggled with nerves before every game has helped you handle anxious situations at Harvard. Can you single out your most anxious moment as president?

FAS faculty meetings.

My final question: What is next for you?

I want to learn to be a historian again. That’s my first goal. So I’m going to dig around the archives, see what I want to write.

This interview has been edited and condensed.