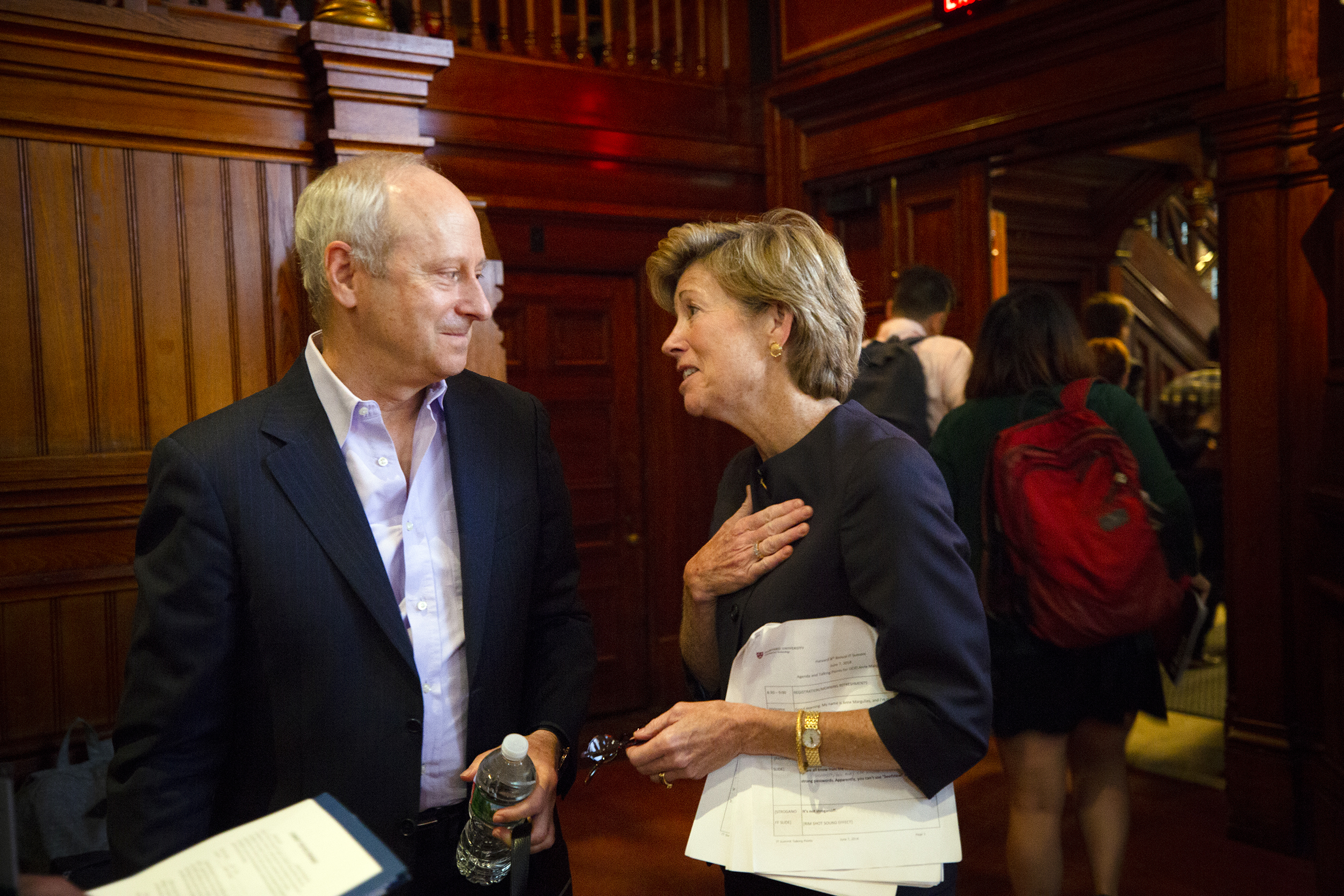

The 8th Annual IT Summit takes place in Sanders Theatre at Harvard University. Anne Margulies gives welcoming remarks, and Iris Bohnet and make keynote presentations. Michael Sandel was one of two keynote speakers at the eighth Harvard IT Summit focused on how technology can contribute to a more diverse, just, and civil society.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

IT for social justice

At annual summit, tech takes a turn to the humanities

Sometimes technology isn’t just about making things faster, easier, or cheaper. Sometimes it’s about making them right.

That was the thrust of the eighth annual Harvard IT Summit at Sanders Theatre on Thursday. Rather than focusing on the promise or problems of innovations in information technology, they focused on the impact technology has on its users.

Specifically, keynote speakers Iris Bohnet, the Roy E. Larsen Professor of Public Policy and director of the Kennedy School’s Women and Public Policy Program, and Michael J. Sandel, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government, looked at how IT — and IT professionals — can contribute to a more diverse, just, and civil world.

“We know, intuitively, that diversity matters,” said Bohnet, the author of “What Works? Gender Equality by Design.” Noting the need to better understand and control for biases that contribute to gender inequality in talent recruitment and development, she asked, “How can we design diversity, inclusion, and belonging in our meetings, on our screens, and in our classrooms?”

Bohnet said the first step is understanding how deeply bias is ingrained in all of us. Using examples of visual patterns in which we “see” what we expect to find and citing the Columbia business school case that showed that venture capitalist Heidi Roizen was perceived as both more likable and more employable when she was called “Howard” Roizen, Bohnet challenged the audience to acknowledge the pervasiveness of such prejudices. Moving onto advances such as blind auditions, in which orchestras evaluate potential new members from behind a curtain, she showed how thwarting expectations can produce more equitable results.

“This is what it is going to take,” she said, noting that the percentage of female musicians in top U.S. orchestras has increased approximately 30 percent since 1970, when the new audition processes were instituted. “We have to go into our systems and de-bias our procedures,” Bohnet said.

“We have to go into our systems and de-bias our procedures,” said Iris Bohnet.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Bohnet said that so-called “diversity training” does not work, but there are many other ways to replicate this symphonic success. Intentionally avoiding gendered language in employment ads, for example, helps those doing the hiring “benefit from 100 percent of the talent pool.” Comparing applicants to each other, rather than to an imagined ideal candidate who likely conforms to a preconceived notion of gender and race, also reduces bias.

Bohnet said that more tech startups are now working on applications designed to help equalize hiring and promotion, and asked the assembled professionals to consider working on such technologies themselves. “You all, with your amazing expertise and knowledge, can help us make our research accessible to the world in a way that is useful,” she said.

Sandel, whose course “Justice” is one of the most famous taught at Harvard College, briefly revisited the 2005 breakthrough that made that course the first Harvard offering to be freely available online. He said the course was initially conceived as a public television offering, with the web component merely an afterthought.

“We were astonished that tens of millions of people wanted to watch lectures on philosophy,” he recalled. “And people didn’t just listen, they debated with one another. People around the world were interested in listening together, in arguing together. I wanted to push further.”

Sandel showed the audience a clip of an interactive, global discussion on the merits of free speech. Using 60 television monitors, participants from Canada to Iran exchanged at times heated, but always polite arguments, while Sandel moderated.

Michael Sandel takes an audience question following his presentation on the detrimental effect of anonymity on internet discussions.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Sandel said the clip highlighted technology’s potential to bring people together to further civil discourse. He also pointed to the very real limitations of social media platforms that may be contributing to its breakdown. Acknowledging that lack of moderation may allow discussions to descend into “invective and obscenity,” he said he believes that the general anonymity of most online discussions — the lack of faces and real human voices — is also a factor in lowering the level of discourse. Giving participants faces as well as voices, he believes, can help make such discussions inclusive rather than abusive.

“Listening can be hurt by prejudice,” Sandel said. “But it can be deepened and enriched by a human presence that is missing if there’s anonymity.”

Professor of Sociology Rakesh Khurana, Danoff Dean of Harvard College and Martin Bower Professor of Leadership Development at Harvard Business School, the afternoon keynote speaker, addressed the important role of inclusion and belonging in the academic experience.

“This year we had the most diverse student body in the history of Harvard,” he said, citing Harvard’s commitment to attracting the broadest possible pool of talented students, along with need-blind admissions and a strong financial aid program. But he added that diversity is not enough — Harvard also must foster an inclusive environment where everyone can bring their “full selves” to the pursuit of excellence.

“It is unusual for a company or organization to be at the top of their game for 40 years, never mind 400,” he said. “Our capacity to adapt is both our biggest challenge and our biggest opportunity.”