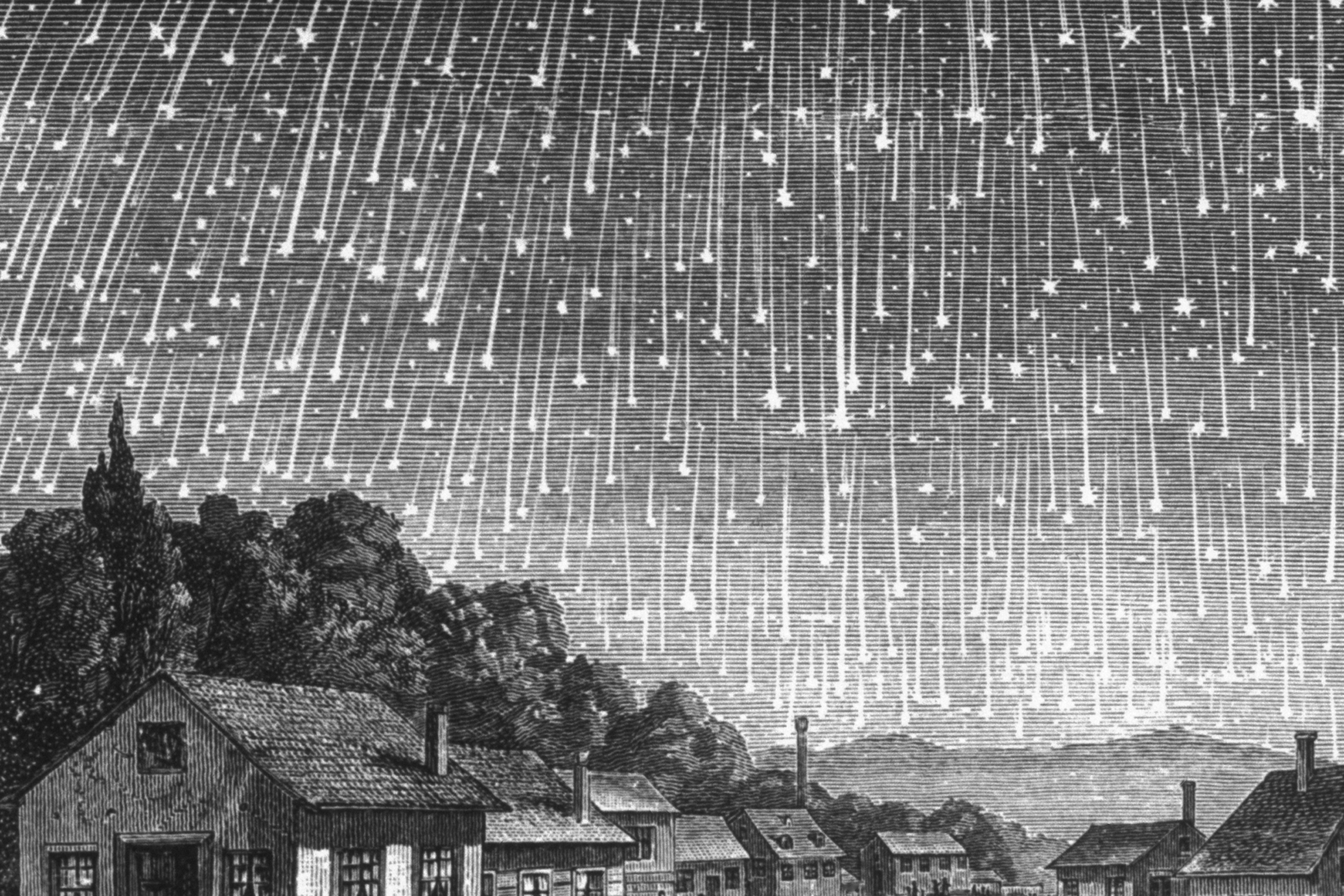

Escaped slave Jane Clark’s narrative includes her recollection of the Leonid meteor shower of 1833: “Children … ran along trying to catch the stars as they fell.”

Wikimedia Commons

Second life for slave narrative

Scholar hopes project will inspire similar efforts: ‘There were thousands of people like Jane Clark’

Robin Bernstein was deep in the archives of the Cayuga Museum of History and Art in Auburn, N.Y., researching her forthcoming book on for-profit prisons, when Jane Clark interrupted her.

Clark’s slave narrative was vaguely familiar to Bernstein. The Harvard scholar wanted to learn more. Soon, she was sharing what she discovered.

“She had an extraordinary life. There were thousands of people like Jane Clark, and I’m proud I was able to deliver one of these thousands of stories,” said the Dillon Professor of American History, who published Clark’s narrative in Common-place, a journal for scholars and teachers of early American history. “There are probably narratives like this in hundreds of depositories across the Northeast, and I’d be delighted if this inspired others to dig out stories like this.”

After surviving five floggings, Clark resolved “to escape or die in the attempt.” She was 34 years old when she fled in 1856, hiding in a cabin for 11 months.

Bernstein, also a professor of African and African-American studies and of studies of women, gender, and sexuality, said that Clark’s life was one of ordinary grace in the face of grave challenges. Enslaved from infancy, sold at age 8, Clark subsisted on a pint of corn a day and suffered the whip for serving breakfast late.

Her story was recorded by Julia C. Ferris, who boarded at the house where Clark lived and worked. In 1897, Ferris read Clark’s narrative before the Cayuga County Historical Society.

Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, called the “as-told-to” narrative, which came as part of the second wave of American slave stories recorded after 1866, “a significant work to the canon of slave literature.”

“We have 102 books written or narrated by former slaves before 1866 and about as many after,” he said. “Cuba received 2½ times as many Africans, but has only one slave narrative. In Brazil, there are virtually none. It’s phenomenal that African-Americans created the largest body of literature in the history of slavery.”

“We have a great deal of knowledge about slavery and escapes from slavery, but it’s very scattered,” said Bernstein. “This is my small attempt to unscatter one piece of the knowledge.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Clark’s story adds a puzzle piece to the larger picture of slave experiences, Bernstein said.

“There is so much that nobody has paid any attention to,” she said. “We have a great deal of knowledge about slavery and escapes from slavery, but it’s very scattered, and this is my small attempt to unscatter one piece of the knowledge.”

In her narrative, Clark describes a childhood of abuse. After surviving five floggings, she resolved “to escape or die in the attempt.” She was 34 years old when she fled in 1856, hiding in a cabin for 11 months. The following year, she and her brother obtained forged passes to travel to Washington to see President James Buchanan’s inauguration. She stayed in Washington for two years, passing as a free woman and working as a servant. Her brother had moved on to New York. In 1859, having secured a train ticket, she joined him.

“Her story reminds us an escape often didn’t take days or months. It could take years,” Bernstein said.

Among the narrative’s many moving passages is Clark’s recollection of witnessing the Leonid meteor shower while making one of her seven daily trips for water in 1833.

“It was on one of these early morning excursions that she saw the ‘stars fall,’” Ferris wrote. “This scene is vivid in her memory. The children were on their way to the spring. They were not old enough to be alarmed by the unusual sight but ran along trying to catch the stars as they fell.”

The account of the Leonid event deepened Bernstein’s conviction that Clark’s narrative deserved a wider audience.

“She wasn’t extraordinary, but that’s exactly why I had to share it. The fact she never gave a speech or ran for Congress doesn’t mean she didn’t matter. She’s one of many, many stories and it deserves to be heard,” she said.