Photos by Kai-Jae Wang/Harvard Staff

A summer of service to cities

Through the Bloomberg Harvard Initiative, student fellows help mayors to improve lives

As people increasingly embrace urban life, it’s ever clearer that crowded, complex cities simply must work. Politics and provincialism can’t get in the way of performance.

Now, with the federal government locked in partisan disagreement over how much of a role, if any, it should play in people’s lives, the breakthroughs on many of the most acute civic problems are coming from America’s city halls.

Mayors and other top city officials are the busy urban mechanics charged with ensuring their communities not only function but thrive. Consumed with their daily responsibilities, they have neither time nor teaching to evolve from managers into civic trailblazers. To change that, the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative is working to boost the effectiveness of today’s local leaders while also building a pipeline to train the next generation.

To further that goal, 16 Harvard students embedded themselves for 10 weeks this summer in mayors’ offices around the country in a new fellows program targeting persistent local problems. These efforts ranged from helping officials in Laredo, Texas, understand why a third of households remain in poverty for generations, to developing a comprehensive plan in Charleston, S.C., to confront the shortage of affordable housing, to assisting low-income parents of children up to age 3 in Baton Rouge, La., to ensure they are ready for kindergarten.

The Gazette traveled to those three heartland cities to learn about the fellows’ projects, to see how they were making a difference, and to chronicle how being immersed in cities, working side-by-side with officials and staff, influenced their sense of what government can accomplish. The Gazette also spoke with mayors and city leaders about the impact of the fellows’ work.

Here’s how the program is playing out on the ground.

Mapping patterns of poverty in Laredo, Texas

Santiago Mota

Video by Kai-Jae Wang/Harvard Staff

Listening to the heated talk about trade and immigration from afar, it’s not surprising that many Americans think relations between the United States and Mexico are fraught, a one-way street where one side “unfairly” takes advantage of the other. But once on the ground in the border city of Laredo, it’s clear the reality is far more complicated.

For starters, the border is busy and still surprisingly porous in both directions. All day, every day, upwards of 14,000 trucks and 15 lengthy trains loaded with goods pass through Laredo, crisscrossing bridges that span the Rio Grande River. More than $214 billion worth of trade moves through Laredo each year, city officials say.

With U.S. companies operating on both sides of the border, workers traverse it like they’re going across town. Many Mexicans from Nuevo Laredo, Laredo’s sister city across the river, head into downtown Laredo to shop, even in 105-degree heat, while many Americans seek out medical services in Nuevo Laredo that are in short supply locally. Almost everyone seems to have family and friends who live just over the border.

“The city of Laredo is known as the No. 1 land port” in the nation, said Mayor Pete Saenz. “Transportation, logistics, international trade is huge here. That’s what has put us on the map. But what has also put us on the map is the fact that we’re still poor.”

“Since 1995 with the introduction of NAFTA [the North American Free-Trade Agreement], Laredo’s economic growth has really exploded,” said Horacio De Leon Jr., the city manager. “The unemployment rate over the last three years has dropped, and it’s historically low. But we find that most of the jobs are low-paying jobs. Our average median income, compared to the rest of the state, is low.”

Indeed, despite a robust economy and a local unemployment rate under 4 percent, 32 percent of households in Laredo, a predominantly Latino city of 270,000, live in poverty. “And it’s been like that ever since I can remember,” added Saenz, a Laredo native. “We’ve got to look at that and see why.”

“We knew the data was there, [but] we’ve never had a platform or a project to really come in and dig deep as to what poverty really looks like in our own city.”

Blasita Lopez, Laredo’s executive director of tourism, marketing and communications

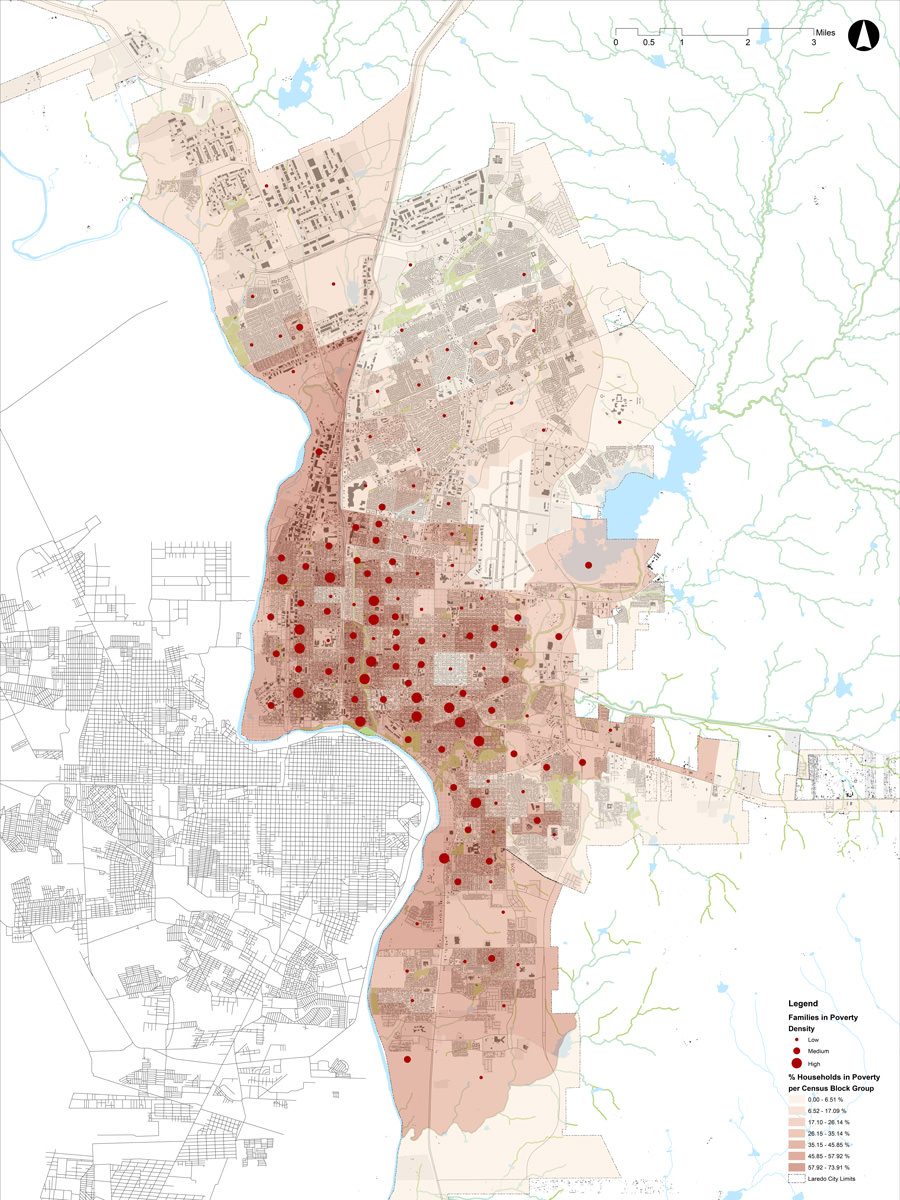

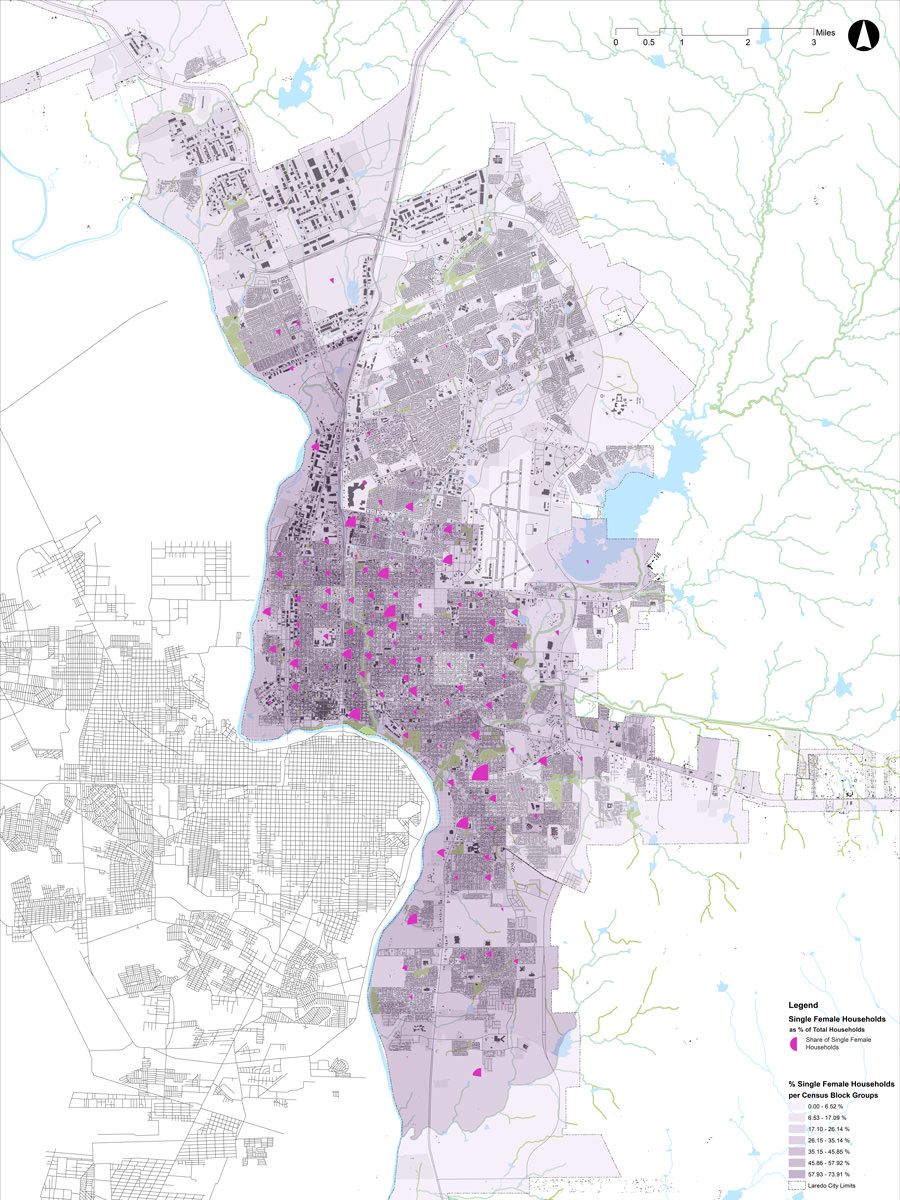

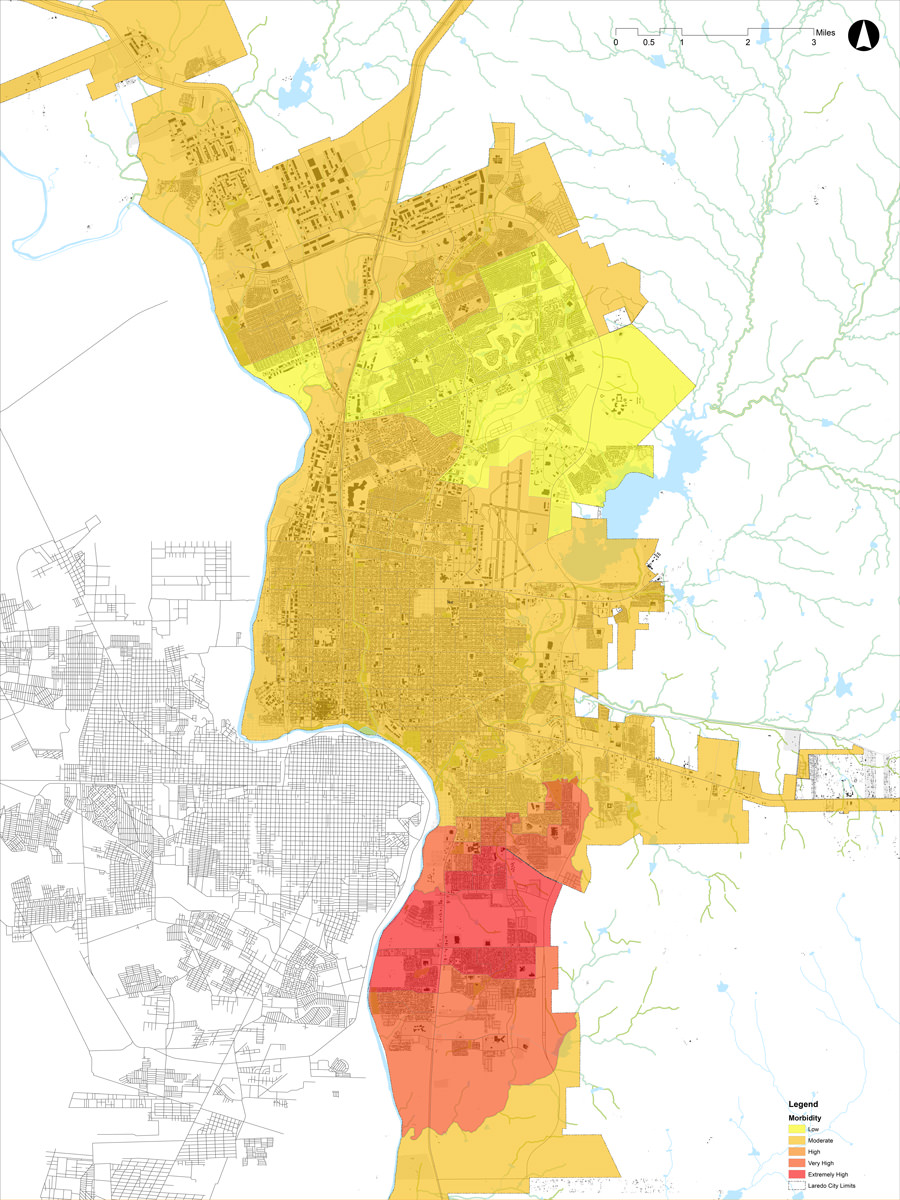

To understand why poverty is so persistent across generations, city leaders asked Santiago Mota, who is pursuing a master’s in design engineering, a joint degree program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) and the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), to create a “heat map” of Laredo using GIS (geographic information system) data and department records to measure need block by block and to pinpoint underlying local factors driving ongoing poverty. City officials will use Mota’s maps to identify not only where the poorest residents live and the demographics of their households, but also what physical, social, and economic conditions are in play that contribute to their poverty. The officials will gauge what resources are needed to change that, and which ones are currently making a difference or not.

“There are two ways to understand poverty,” Mota said about his mapping mission. “I think the structural definition applies to the city because the environment and the conditions people are living in describe how people become impoverished and why they remain impoverished, and that is a more difficult thing to explain because it requires a lot of data. So, it matters where they live, what their health condition is, what their income is, what their access to services is, etc.”

Mota broke down poverty rates by neighborhood, visualizing income data from 2012 to 2016 in a choropleth map.

He combined a choropleth map and pie chart to pinpoint where single-female households are concentrated using 2012-2016 data from the U.S. Census Bureau and American Community Survey.

Using a hot spot analysis map, Mota scored the morbidity of Type 2 Diabetes with a dataset provided by the nonprofit Gateway Community Health Center in Laredo.

“We knew the data was there, [but] we’ve never had a platform or a project to really come in and dig deep as to what poverty really looks like in our own city,” said Blasita Lopez, Laredo’s executive director of tourism, marketing, and communications. “We know what the Census Bureau statistics tell us, but we don’t really know what single individuals are dealing with in their homes, in their circumstances, in their lives — and is there a way that the city can repurpose the resources that we already have to maybe address a particular issue?

“We haven’t made any assumptions. We’ve really left it open so that the data can tell us the story, and then we can retool what we’re doing and how we’re doing it,” she said.

An architect from Mexico City with an extensive background in mapping, Mota was drawn to the Laredo project, in part, by the chance to live and work on the border as a Mexican student in the United States. “It’s a good opportunity to be here safely and with some level of access to understand the nuances of what’s happening in terms of immigration,” he said.

Mota was particularly intrigued by the project’s open-ended, trailblazing nature. The city had never attempted such an ambitious mapping effort, which meant he had to do extra legwork finding, cajoling, collecting, and sifting through data from city departments and agencies.

“Really going into the raw data and working from that level up, that was a real challenge,” he said.

Starting the project from the ground up was liberating, he said, in that it allowed him to do a deeper analysis, set the parameters of the mapping, and closely define what the maps would and would not measure.

“Describing poverty through maps would require studying the environment, understanding the physical infrastructure of the city, and also the social components, so it had all these dimensions that made it interesting,” said Mota.

Downtown Laredo, where city hall is located, has boarded-up buildings and vacant lots, but also offers plenty of intriguing potential for improvement, Mota said.

Laredo has “good bones.” Laid out in the late 1700s on a European-style grid, block after block has intriguing examples of Spanish colonial architecture and walkable, tree-lined streets, unlike the rest of the city, which has wide avenues lined with strip malls.

“The beautiful thing about Laredo is that, from the very beginning, it has a grid that works,” unlike, say, Houston, which has always been sprawling, said Mota. As many American cities have realized in the last two decades, a smartly revived downtown can have a powerful and positive multiplying effect on the social and economic life of a city, if harnessed correctly.

Nearly all of Laredo’s real estate growth and increased property value in the last two decades has occurred 20 minutes north of the city center, and has provided no measurable benefit to downtown businesses or residents, Mota told city officials during one of his periodic briefings about the project. Jobs also have shifted to the north side, forcing residents to commute farther across town.

Laredo’s border location also means the city does not entirely control its own fate. Over time, significant state and federal interests, like roadways, security fences, and border crossing stations, have intruded on the city landscape, disconnecting large sections of town from others.

“The infrastructures that service the border and service both nations came in and segmented this grid. It’s basically a contradictory condition where we have all these bridges connecting two nations, but we have elements that fragment the city in the other direction,” said Mota.

An archival map shows Laredo’s original, well-organized grid, which has become disconnected over time by the roads, railroads, bridges, and other infrastructure servicing border security and commerce.

In addition to the heat map, Mota will give Laredo a framework so city agencies have clear, specific data points to refer to and build on. He also hopes to create a model to identify indicators of poverty specific to Laredo, so the city can plan more strategically and develop an action plan to address them. “Once you can measure, then you can manage,” said Saenz.

In the coming weeks, the maps and the information used to create them will be incorporated into the first phase of Laredo’s Open Data Project so residents can not only learn Mota’s findings but conduct their own analyses to augment them.

“This is really important because having a website with all these maps and all this data will allow not only city officials but the community to understand itself better,” Mota told city officials. “Everyone now is connected to the internet. They can browse and they can see these maps and they can say ‘Wow, there’s a problem in this section or that section. What can we do?’ So, it can be empowering not only for the government but for the whole community.”

In all, Mota describes his experience in Laredo as “incredible.”

“Being able to ask tough questions to city officials, to have access to their data, [and] extract meaningful data points to contribute a larger explanation has been invaluable,” he said. “And understanding, also, all the pressures that they’re facing as a local government has been extremely interesting.”

An affordable housing plan for Charleston, S.C.

Natasha Hicks

Video by Kai-Jae Wang/Harvard Staff

With meticulously restored Colonial and Antebellum homes sporting shiny wooden shutters, and flickering gas lanterns lining palm-fringed, cobblestoned streets, Instagram-darling Charleston hardly looks like a city in need.

By many key metrics, this busy port is thriving. It’s consistently ranked a top tourist city by travel magazines, drawing 7 million visitors annually. It has a burgeoning tech sector, with 250 companies in that field working in “Silicon Harbor,” bringing in jobs, investment, and skilled workers from out-of-state. The area also has benefitted from Mercedes-Benz and Boeing building manufacturing facilities in nearby North Charleston.

Yet local officials say that many of the factors that have made Charleston suddenly so popular — its historic character and charm, its small size and human scale, its waterfront location, its rich cultural diversity and fine quality of life — have rapidly pushed real estate prices and rents to historic highs, and many residents are feeling the pinch.

“For folks who have lived here for some time, what they’ve experienced is rapidly increasing housing costs and stagnant or slowly increasing wages, so the local effect has been extreme,” said Jacob Lindsey, director of Charleston’s Department of Planning, Preservation and Sustainability.

In response, the city sought help from a student fellow to develop its first strategic plan for affordable housing. “That’s why we feel we are moving into a very extreme time when we have to take extraordinary measures,” said Lindsey.

Brimming with historic charm, downtown Charleston has been discovered by luxury real estate developers and deep-pocketed buyers, which has led to an urgent affordable housing crisis for residents who’ve been suddenly priced out.

iStock

By August, the year-to-date median sales price for a single-family home downtown had risen to $975,000, 8.3 percent over 2017, while the median price for condominiums and townhomes was up 6.8 percent, to $588,000. Rents have similarly spiked, forcing many young professionals to share apartments with two or three roommates. In a city with many tourism jobs, the costs of living are now outstripping what workers in the hotel, bar and restaurant, retail, and recreation businesses can afford to pay. The average Charleston household now spends 56 percent of its income on housing and transportation.

Housing is also in short supply, with some homes even boarded up because owners cannot afford the high cost of repairs. According to the city’s Department of Housing and Community Development, there are about 30,000 more households that need units than are available downtown; about half of those need affordable housing.

“I’ve always been interested in … how can we use design to dismantle some of the systemic inequities that are built into the urban fabric,” said fellow Natasha Hicks, a Los Angeles native who is pursuing a master’s in urban planning and urban design with a concentration on risk and resilience at GSD.

Trained as an architect, Hicks said that as she began to learn more about housing and economic development at GSD, she saw how the country’s shortage of affordable housing is reshaping many cities’ trajectories, literally determining who lives and works in them, undercutting quality of life for many, and threatening to erode decades of gains in employment and economic development.

Natasha Hicks, pictured below, discusses her work in Charleston this summer.

Though many cities struggle with affordability, Charleston has what Hicks calls “a layer cake” of barriers and issues that make the problem especially onerous there, a puzzle that drew her to the project.

“Not only do you have the baseline supply-and-demand issues, but you have seismic and flooding issues, which [drive up] the cost of building here. You also have a very limited amount of land on the peninsula, and a combination of an aversion to building higher or densifying,” she said. “And on top of that, there’s this historic layer that makes it very difficult for developers to build here because there’s a lot of policies and codes to make sure [buildings] fit within the character of the downtown architecture.”

Additionally, the state government has opposed efforts to require local developers to contribute to the affordable-housing stock, and Charleston’s meager public transportation infrastructure makes developing such housing outside downtown, where land is less expensive and building regulations less stringent, no easy alternative either. City officials say creating affordable housing in the suburbs raises equity issues, imposing new costs on poorer residents and on the city through longer commutes, reduced access to vital services, added traffic, rising pollution, and increased road maintenance that in the end could hurt the local economy.

With tourism the city’s top economic driver, businesses that rely on lower-wage service workers such as waiters, hotel staffers, and tour guides find it harder to hire and retain staff when those employees have to move ever further from work to live.

Since the burgeoning city had not confronted its housing crisis in a formal, systematic way before, Hicks’ ambitious task was to develop Charleston’s first strategic plan for affordable housing, one that includes a policy framework and a toolkit the city can use to realize its goals over the next five years.

“Essentially, my work is just to look those barriers straight in the eye and figure out what the toolkit and plan of action should be,” she said.

Additionally, Hicks has been assisting the city’s beleaguered effort to redevelop a large swath of land on the East Side of downtown that has been fallow since the Cooper River Bridge was demolished more than a decade ago. Straddling two historically African-American neighborhoods, a privately built hotel is rising, a 300-unit loft building with 70 affordable units will open soon, and the Charleston Housing Authority, which oversees federally subsidized public housing, is building 62 low-income apartments, including five that can be purchased. Though the former industrial site presents environmental challenges, the city hopes to take advantage of this rarely available raw acreage to build affordable housing.

“Cooper River Bridge is a really interesting opportunity because it is in a neighborhood that is gentrifying,” said Hicks. “It hasn’t fully gentrified yet, but it is definitely on the cusp. So that’s a great site to put a lot of these tools in one spot and really make a signature site that shows the city’s investment in affordable housing and demonstrates that to the larger world.”

As with many cities, rising property values resulting from redevelopment of urban centers and waterfronts has undercut many African-Americans. As recently as the 1980s, downtown Charleston had a majority-black population and a high crime rate, and was viewed as a less-desirable place in which to live and work by many whites, who lived in the suburbs. That reality has now inverted, with whites displacing many African-Americans who sometimes can no longer afford to keep the homes they’ve lived in for generations and feel pressed to sell to developers or who seek less expensive rents outside the city center.

“Nobody’s going to say ‘No, don’t make my neighborhood better.’ But residents don’t want that to happen without them, and they don’t want to be forced out by price increases. It is about choice, the choice either to stay or leave. And a lot of times, what we’re seeing in many cities is that people don’t get that choice — they’re just priced out.”

Natasha Hicks

Though its technical meaning refers to increased property values, gentrification often has racial and socioeconomic factors intertwined, with the benefits and opportunities rarely distributed in ways that favor those who have less.

There are some pluses. In Charleston, longtime African-American residents are finally seeing derelict buildings restored, vacant lots developed, much-needed services like banks and grocery stores return, and crime rates plummet. But revitalization even at best is often a double-edged sword.

“In some neighborhoods, you want to see investment and you want to see new development, and many people in the neighborhood would like to see … improvement to their neighborhood. Nobody’s going to say ‘No, don’t make my neighborhood better.’ But residents don’t want that to happen without them, and they don’t want to be forced out by price increases. It is about choice, the choice either to stay or leave. And a lot of times, what we’re seeing in many cities is that people don’t get that choice — they’re just priced out,” said Hicks, who last year was co-president of the GSD African-American Student Union and represented GSD on Harvard’s Presidential Task Force for Inclusion and Belonging.

“There are underlying racial tensions at play here that are deeply rooted in the city’s history,” she said. “So when people use the term gentrification, it has an even more visceral meaning, as it is about a feeling of erasure. There is an extreme connotation of ‘you’re actively erasing African Americans from the peninsula.’ “

The city has taken steps in the last decade to catch up with changing market forces. But housing advocates and officials say they’re not sufficient to counter the prevailing trends. In addition to financing affordable rental and ownership housing, the city has several programs to help residents afford costly but necessary repairs to comply with strict historic building standards so they can stay in their homes and not have to move because of leaky roofs or broken windows.

But a voluntary program to entice developers to build affordable units by letting them increase project density, if they make a percentage of units affordable or pay a fee toward the city’s affordability programs, has made little dent in the housing shortage. Most developers opt to pay a onetime fee, between $3 and $4 per square foot, rather than set aside 20 percent of units as affordable for 25 years. So far, only one developer has agreed to build affordable units.

“The fee structure is too low, so, for a developer, it’s much easier to give a onetime fee than to actually build the units,” said Hicks.

Despite having what on paper looks like the upper hand on developers in such a heated market, the city has little leverage to demand more from developers. The state has opposed inclusionary zoning legislation, a tool that other cities use to link approval of market-rate units to the creation of affordable ones.

“You can’t compel them. You have to cajole them and hope that it will work,” said Florence Peters, an officer in the Department of Housing and Community Development.

During her fellowship, Hicks was busy pulling together research, meeting with city officials, real estate developers, housing advocates, and other stakeholders to gather ideas and evaluate how best to address overlapping and sometimes competing interests, and to create a detailed map of Charleston similar to what New Orleans did after Hurricane Katrina. The map uses vacancy rates and other socioeconomic metrics to look at each neighborhood and see spatially where there might be opportunities for affordable development and where targeted city services and attention would help.

“What I recognized early on is that I’ve dived in on this massive project, and that’s exciting. I love that everybody in the city has supported me in this really ambitious move, because it’s a bit insane, but I love that they were kind of onboard with the crazy,” said Hicks with a laugh.

Given the plan’s vast scope and complexity, Hicks will continue working on it through the fall semester, consulting with Charleston officials from Cambridge until it’s complete. “I’ve just begun. I’ve just opened this chapter for the city, and we have this new initiative,” she said.

No matter how helpful Hicks’ five-year plan may prove, though, it won’t make much difference if no one in Charleston can see it through, so ensuring that happens will be the “biggest challenge,” said Josh Martin, special assistant to the mayor and Hicks’ project supervisor. The city is close to finalizing funding for a dedicated staff position in the upcoming budget.

“It’s a project that requires one person to be spending every single day on,” said Hicks. “I think, with a lot of strategic plans, what happens is a department will take it on, they’ll make it, and it goes on a shelf. There’s no one tasked, there’s no champion who’s constantly thinking [about it] and holding people accountable, making sure things are implemented. That’s the only way it’s going to get done.”

Boosting children in Baton Rouge, La.

Steven Olender

Video by Kai-Jae Wang/Harvard Staff

Just an hour’s drive northwest of New Orleans, Baton Rouge shares with that city a Creole and Cajun cultural heritage and a prime perch along the ruddy Mississippi River. As a busy working port and state capital, Baton Rouge enjoys little of the Crescent City’s cachet with tourists and conventioneers, yet the city suffers many of the same entrenched economic, social, and educational difficulties as its better-known cousin.

Baton Rouge is a study in contrasts, where the embrace of history and tradition bumps up against emerging signs of fresh energy and yearning for change. A downtown revitalization effort has yielded the Shaw Center for the Arts, a sleek museum, performing arts and theater complex, and a library under construction near city hall. Yet just blocks away are occupied homes with boarded-up or broken windows, sagging roofs, and rusted-out vehicles in the yards. There are tidy new bicycle and jogging paths illuminated by ornate lamps along the Mississippi, part of a move to restore public access to the waterfront. Yet the view is not of lazy sailboats but of rusty barges loaded with trash and of sputtering smokestacks at the petrochemical refineries that form the economy’s backbone.

Historically, Louisiana has a poor track record in K-12 education. The state ranks at or close to the bottom in national benchmark testing, with 4th graders ranked 43rd in reading and 45th in math and 8th graders 48th in reading and 50th in math, according to a National Assessment of Educational Progress report. The state has made some strides in recent years to strengthen its early childhood education policies and quality standards, such as ensuring that teachers have the requisite training and professional development and that curricula is comprehensive, aligned, supported, and culturally sensitive.

Still, 46 percent of the state’s children entering kindergarten do not have the cognitive, social, emotional, or behavioral skills, nor the executive functioning deemed necessary to transition to school successfully. In Baton Rouge, 56 percent of kindergarteners were rated not “school ready” during the last academic year.

To help change that, the city last fall launched an effort to help young children get on track, based on principles and strategies from “Cradle to Kindergarten,” a 2017 book by social scientists who argue it’s critically important for children in low-income households to get the same intellectual stimulation and learning opportunities during their early years as middle- and upper-income children receive if there’s any hope of closing the achievement gap at the heart of inequality.

The incomes of a third of Baton Rouge residents fell below the federal poverty level in 2016, and nearly 41 percent of children live in families below the poverty line. Unlike most educational programs, which don’t begin until kids are in classroom settings, “Cradle to K” encourages parents to prepare their young children for school by stimulating and teaching them based on principles of early childhood development.

Steven Olender, pictured below, discusses his work in Baton Rouge this summer.

“What we talk about on a national level is universal pre-K and about improving schools and things like that, which are all really important, but universal pre-K starts when kids are 4, and 80 percent of brain growth has happened between 0 to 3. Kids are already so far behind. It’s really important for us to intervene there, but it’s also really difficult to do,” said fellow Steven Olender, who’s focusing on child and family policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS). “So, I was very drawn to Cradle to K because it was working to do that in what I think is a very smart way.”

Operated under the city’s Head Start program, Cradle to K first tries to get parents to understand how what they do in their children’s first few years has lifelong implications and to help them see the benefits of adopting simple, everyday habits that promote children’s development and well-being. Then the program gives parents tools and support so they can become more confident and engaged with their children.

“It’s so much more than giving folks diapers and telling them ‘congratulations.’ The parents have to be empowered if we’re going to empower the children,” said Baton Rouge Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broome, the driving force behind the local Cradle to K initiative. “If the parents are feeling depressed, down, disgusted, it’s not going to be a good connection for that new baby, so empowering those parents is so important.”

Because research shows that people are more likely to accept new ideas that challenge their own beliefs and change behavior if information comes from a trusted source like a family member, friend, or neighbor, getting influential local parents committed to Cradle to K’s core themes and techniques — and then getting them to lead discussions and share what they’ve learned — is a key to the initiative’s peer-to-peer outreach.

“It’s so much more than giving folks diapers and telling them ‘congratulations,’” Baton Rouge Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broome says about her city’s Cradle to K program. “The parents have to be empowered if we’re going to empower the children.”

“A lot of these types of programs, especially targeting low-income families, really focus on what families are perceived as not knowing and not being able to do and seeing them just as recipients of what others have to offer,” said program manager William Minton, who supervised Olender. “Our approach is trying to build on the strengths already in the community, and, while there is a guiding component to that, the parent voices are front and center.”

Over the summer, Olender gathered and analyzed data that underpins Cradle to K’s approach and strategies, and put together a sweeping report that the city will use for partner organization training and parental messaging.

The project was a natural fit for Olender, who has an extensive background in children’s issues. Before returning to school for his master’s, he worked with court-appointed special advocates for children in the Texas foster care system. In 2015, a federal judge ruled that Texas had been negligent because 12,000 foster children had been exposed to more physical, emotional, and sexual trauma in the state’s care than in the abusive homes they had been removed from. The state fought that ruling, prompting Olender to rethink his career path.

“I wanted to go to school because I think we as a country are not doing right by children, by any stretch. And I looked at what was going on in Texas and said: Someone needs to be helping and reforming the system,” Olender said.

So far, two dozen local organizations — including a new children’s museum, the local PBS affiliate, and Louisiana State University — have signed on to Cradle to K to help parents ensure that their kids reach the developmental milestones they need before kindergarten.

“We are a city at risk. We have the same statistics for mental illness as we have for illiteracy, 1 in 5. And we’re creeping up to 1 in 4. We have 99.99 percent free lunch in our schools,” and many failing schools that have been taken over by the state, said Mary Stein, assistant library director at the East Baton Rouge Parish Library, a Cradle to K partner.

For decades, the public library system has been at the forefront of child literacy efforts in Baton Rouge, holding story times at local Women, Infants & Children (WIC) clinics, giving books to families, and operating a bookmobile to take learning to children whose families may not know about all that libraries offer. “For many years, the census reported that in Louisiana there was 0.7 book in each home. We wanted to break that cycle,” Stein said.

The initiative is organized around three pillars of effective parenting: practicing patience, encouraging curiosity, and teaching through conversation. Several “parent club” events gathered families in a party-like atmosphere to share everyday experiences and parental frustration while also getting information about the local educational, health, and career services and resources available. While the parents talked, their children explored STEM, reading, and creative activities run by partner organizations that combine learning and fun. The Cradle to K organizers hope to get more groups and parents involved, soliciting testimonials from respected community figures and from parents about the program’s value, and training mothers and fathers to run smaller parent club events.

The goal is to convey that by making small changes in how parents interact with children every day — such as asking questions about what they see in a grocery store or telling stories — they can help ready their children for school.

Though Olender worked on children’s issues previously, doing so through a city government has been a “fascinating” learning experience.

“Universal pre-K starts when kids are 4, and 80 percent of brain growth has happened between 0 to 3. Kids are already so far behind. It’s really important for us to intervene there, but it’s also really difficult to do.”

Steven Olender

“Every person who you talk with and everything that the city does comes with all of these expectations that people have of a city and what people think a city can do versus what a city actually can do. That can be very limiting for cities because people expect you should do a lot more,” he said.

Even though city governments have power, their officials have to think carefully about what’s possible, as well as the rippling consequences of every decision before taking action, which can leave citizens frustrated at what seems like the incremental pace of change.

“There are so many moving pieces, and yet it seems like everything should be simple,” said Olender. “Working in nonprofits, all that you are focusing on is the mission of your nonprofit, and people don’t expect you to be responsible for everything else.”

In the months ahead, city officials will expand Cradle to K to more partner organizations and more neighborhoods, using Olender’s reporting and recommendations to develop a communication framework so partner groups share a clear and common set of messages with parents. The program metrics that Olender developed will be shared with partners for feedback as the city decides its next steps.

Now back in Cambridge, the soft-spoken Olender said he at first found it a bit intimidating going from graduate studies to presenting ideas to a mayor, “but it’s also been really exciting in part because so many of the senior leadership have been through the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative training, and they’ve listened to my ideas and have been really open and receptive” to different approaches. Baton Rouge also has prioritized “research and data and wanting to be a city that is well-run and really smart about the ways it does things, and that’s been really exciting, too.”

A new paradigm to help cities thrive

The Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative is a collaboration among Bloomberg Philanthropies, Harvard Business School (HBS), and HKS. The program, which began last fall, first enrolled mayors and two senior officials from 40 U.S. and international cities in a year-long executive education effort to help them tackle problems more effectively, efficiently, and equitably. Later, the participants identified challenges and design projects for the new student fellows.

The idea behind the fellows program was to create deep links involving executive education for city leaders, faculty research on urban issues, student learning and career development, and University involvement in the field.

The inaugural cohort of mayors participating in the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative heard from faculty director Jorrit de Jong (center), during a classroom session at HKS last year.

© Bloomberg Philanthropies

“We really wanted to reinvent the concept of a summer fellowship. We didn’t want to send the students out and, you know, ‘see what you can do’ without any support,” said Jorrit de Jong, the initiative’s faculty director and an HKS lecturer. “Student fellows, instructors, and city executives reinforce each other in a focused, structured way.”

As people continue to leave rural areas and move to cities, how well those urban communities are managed and deliver services to their residents becomes increasingly important. By 2050, analysts believe that 75 percent of the world’s population will live in cities.

But too often, the mayors overseeing those cities face a relentless slate of daily responsibilities and crises, as well as the pressures of public expectations, but often lack the tools, resources, or institutional capabilities to make real progress.

To change that dynamic, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the charitable foundation of businessman and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, M.B.A. ’66, provided a $32 million gift to Harvard to support the first executive education and professional development program for mayors, called the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative.

A collaboration among Bloomberg Philanthropies, Harvard Business School (HBS), and Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), the initiative is a comprehensive, year-long program for city mayors that offers training and support to hone leadership and management skills, share experiences, and collaborate with other mayors to find innovative, data-driven solutions to vexing challenges. On campus, the program is housed at HKS’ Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.

Because senior administrators, such as chiefs of staff, budget directors, and department heads are so critical to implementing a mayor’s agenda and leading organizational change, the participating mayors also choose two top aides for a parallel program.

Throughout the year, participating mayors receive an array of supports, including 360-degree assessments with executive coaching, advising by former mayors, and faculty-led examinations of such topics as using data and evidence, public narrative, and cross-sector collaboration and innovation.

Graduate students play an important role in helping mayors apply the learning and implement change on the ground. More than 60 students have worked with HBS and HKS faculty and staff on research scans, content development projects, field courses, and summer fellowships in mayors’ offices. As they help the cities analyze budgets, implement management tools, and develop innovative approaches to pressing problems, they gain invaluable experience in government.

Using a curriculum developed and taught by faculty from HBS and HKS, the initiative’s works to strengthen leadership and organizational capabilities in cities by supporting current city leaders and inspiring students, future city leaders, through education, research, and daily practice.

Harvard faculty from HBS and HKS, as well as the Graduate School of Education (HGSE), the T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH), the Graduate School of Design (GSD), and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) are collaborating on research to advance the art and science of city leadership. The initiative is also developing teaching cases using experiences, insights, and data gleaned from the mayoral cohorts. Program materials such as case studies, videos, and assessment tools will be made available to the public free of charge.

The initiative’s goal isn’t simply to create a positive, enriching experience for mayors and senior city leaders, but to see a meaningful change in practice, increased progress, and improved everyday lives for residents.

“It’s great if a mayor loves this program and gives it a 5 on a 5-point scale, but we want to know if that learning then really translates into changes in leadership approach and changes in organizational capability,” said Jorrit de Jong, the initiative’s faculty director and a lecturer at HKS.

The inaugural cohort, which included mayors and aides from 29 U.S. and 11 international cities, will reconvene virtually for a concluding session in October to discuss the experience.

Mayors and aides from 40 cities in the United States, Canada, Europe, Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia kicked off the program’s second year in late July. The initiative intends to enroll leaders from 240 cities worldwide during the four-year effort.

For their fellowships, the students had access to 12 faculty members, including de Jong, for coaching, strategizing, problem-solving, reflecting on issues, and organizational support. The students were asked to interview key players to gauge the impact the initiative has made on the cities, which gave the program valuable data points and provided insights for students and city officials.

The goal is to help cities apply the learning from the executive education programs and implement new ideas while exposing students to life in city halls and helping them imagine themselves working in local government, said Glendean Hamilton M.P.P. ’17, senior program manager for mayoral relations with the initiative and coordinator of the fellowship program.

Since cities need leaders with diverse talents and skill sets, the program in its first year recruited student fellows from many disciplines. Seventy-two students applied. The 16 selected came from six Schools (HKS, HBS, GSD, SEAS, the T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the Graduate School of Education).

The fellows wrote blog reports about their work, and some students will share their experiences during a community speaker series this semester at the Ash Center at HKS.

With the new cohort of mayors and senior leaders starting the year-long program, de Jong anticipates there will be even more opportunities for students next summer, which should benefit all involved.

“The student gets a great professional development opportunity. The city gets real, valuable help, and we as a University learn from the things they’re analyzing and the things they’re developing,” he said. “And we get the opportunity to share those lessons with other cities.”