Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Immigration, under the stage lights

Houghton exhibit shows how new arrivals repeatedly influenced, rejuvenated American theater

The history of the U.S. is a story of immigrants. It only makes sense, then, that the tales that people stage — the dramas and comedies — have been deeply influenced by new arrivals. An exhibition at Houghton Library chronicles the fresh talent and innovation that each successive wave of newcomers brought to American theater.

“Treading the Borders: Immigration and the American Stage,” on display through Dec. 15, makes use of the extensive Harvard Theatre Collection to illustrate the influence of immigrants from this country’s earliest days. With materials ranging from the oldest extant American playbill (from a 1750 performance of “The Orphan”) through souvenirs of contemporary works like “Hamilton,” the exhibit examines the broad influence of ethnic groups and nationalities on theater, dance, opera, and other performing arts, even as immigration ebbed and flowed around prejudice, hardship, and restrictive laws through U.S. history.

“Anywhere there is an immigrant community large enough to sustain it, there’s a flowering of ethnic theater — theater in the language of the immigrant,” said Matthew Wittmann, curator of the Harvard Theatre Collection.

Even before this country was founded, Wittman and the show explain, newcomers were bringing their dramatic traditions into the mainstream. With “too many actors in Britain and not enough stages,” as Wittmann put it, English actors such as Walter Murray and Thomas Kean came to seek their fortunes, staging productions of Shakespeare for their colonial compatriots. Before long, however, that dominant British tradition was being changed and challenged by input from the French (via actor Alexandre Placide, for example, who settled in Charleston, S.C.) and others. By the early 1800s, European Jews, Irish, Italians, and — with the San Francisco Gold Rush of 1849 — Chinese immigrants were infusing their traditions and entertainment.

“Anywhere there is an immigrant community large enough to sustain it, there’s a flowering of ethnic theater — theater in the language of the immigrant.”

Matthew Wittmann, curator of the Harvard Theatre Collection, pictured above

Oldest extant American playbill, for “The Orphan,” 1750; Russian-born actress Alla Nazimova, circa 1905.

Images courtesy of Houghton Library

“Treading the Borders: Immigration and the American Stage” is on display at Houghton Library through Dec. 15.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

In addition to adding their individual talents, the show illustrates, foreign-born artists brought new techniques and innovations. Russian-born actress Alla Nazimova introduced the Stanislavski system when she emigrated in 1905, and in the 1960s Yayoi Kusama would come from Japan and help meld art and performance into something new.

The path these artists faced could be difficult. Not only did restrictive laws (starting with the Naturalization Act of 1870) make immigration itself difficult, but the concept of theater itself was often frowned upon in a country founded by Puritans. In response, many performers found themselves split. Some stayed within their own communities, performing in their native languages. Others crossed over by playing what Wittman calls “burlesque versions of themselves to gain access.”

Under the name Barney Williams, Irish immigrant Bernard O’Flaherty made a career out of portraying such Irish stereotypes as Ragged Pat and Patty the Piper, while the Polish Jewish comedy team of Joe Weber and Lew Fields mocked their ethnic heritage (Weber was actually born in New York City) with heavily accented “Dutch” (Deutsch or German) characters in vaudeville.

Harrigan and Hart’s Patrick’s Day Parade Songster, 1874; “Self-Obliteration” by Yayoi Kusama, 1968.

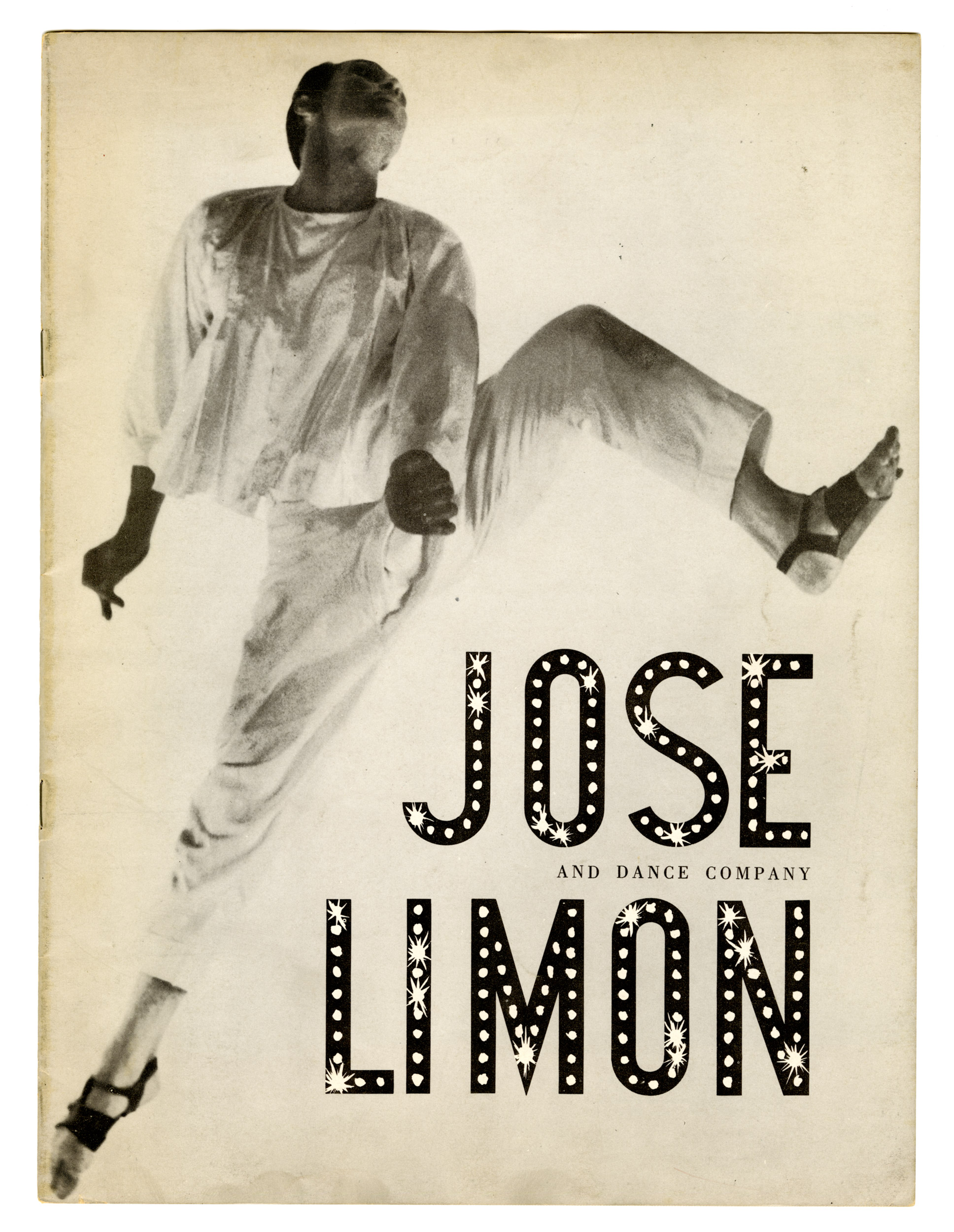

The success of “The Moor’s Pavane” (1949), a ballet inspired by “Othello,” established the José Limón Dance Company as one of the premiere exponents of modern dance, and the Mexican-born Limón’s technique is still widely taught today; Italian-American soprano Rosa Ponselle, circa 1920.

Images courtesy of Houghton Library

Occasionally, talent could cross over. The illustrious soprano Rosa Ponselle did. Born and raised in an Italian-American family in Meriden, Conn., Ponselle debuted in vaudeville as an ethnic act — singing Italian songs as one of the Ponzillo Sisters — at around age 15. Her talent, however, was undeniable, and she debuted at the Metropolitan Opera at age 19.

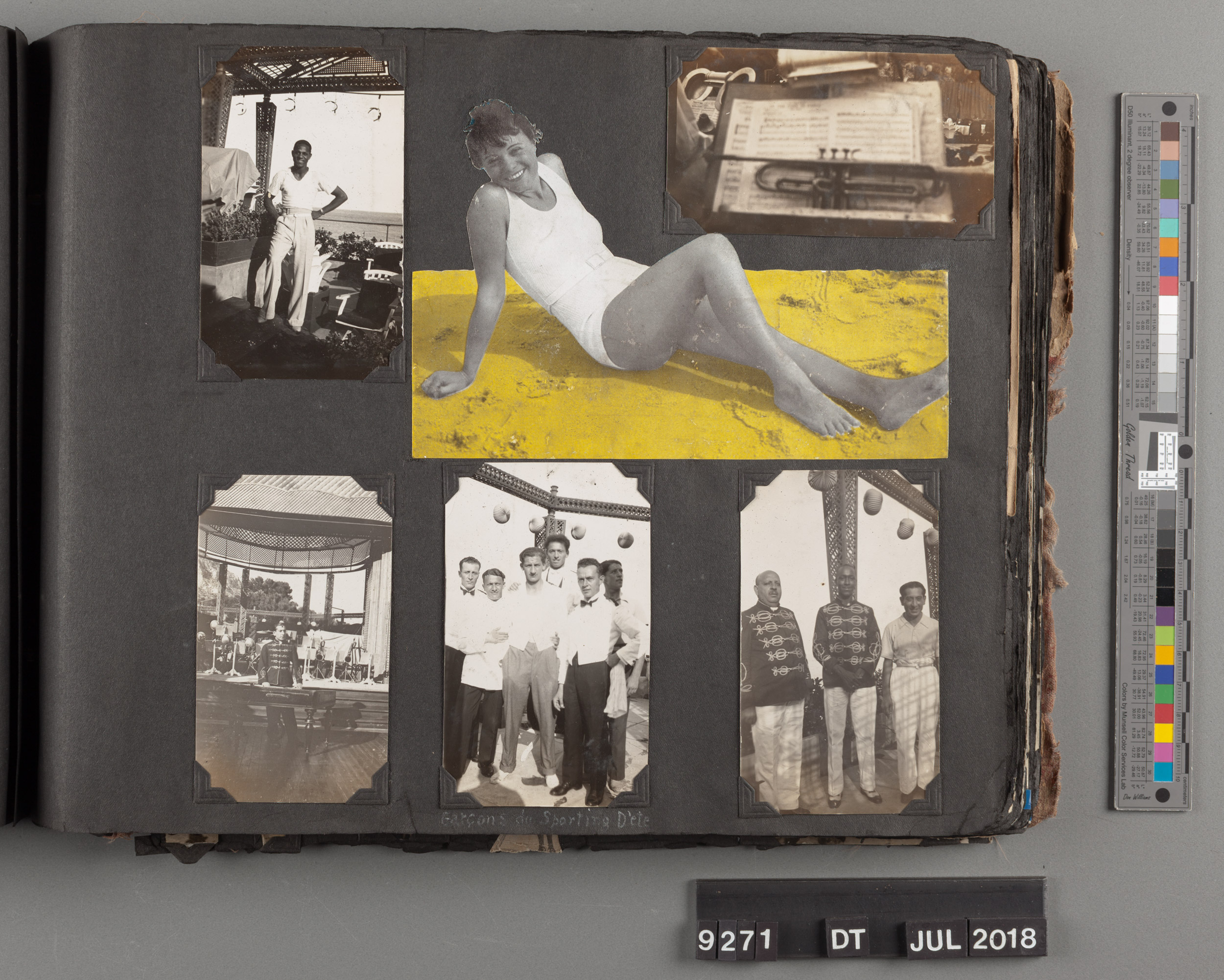

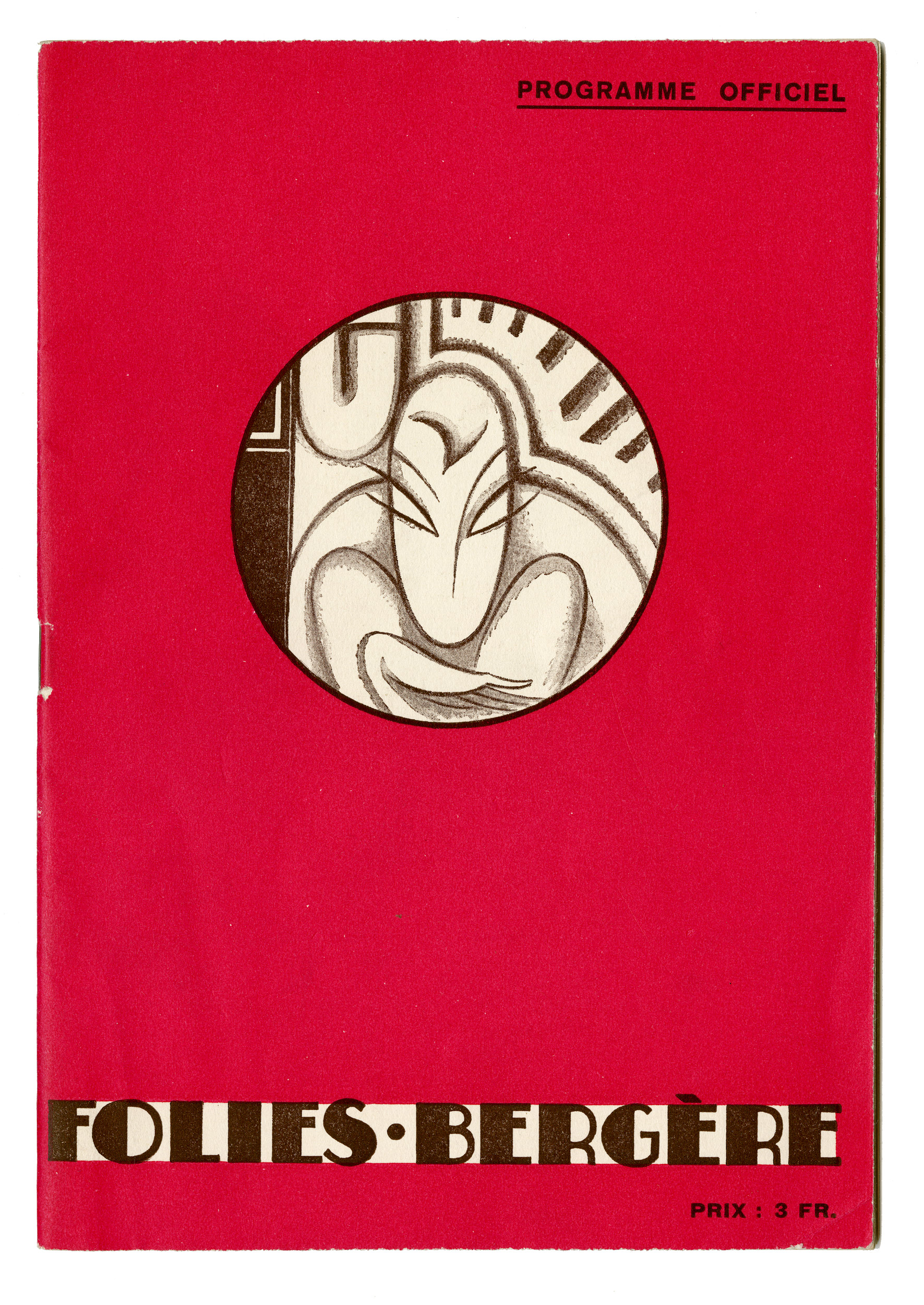

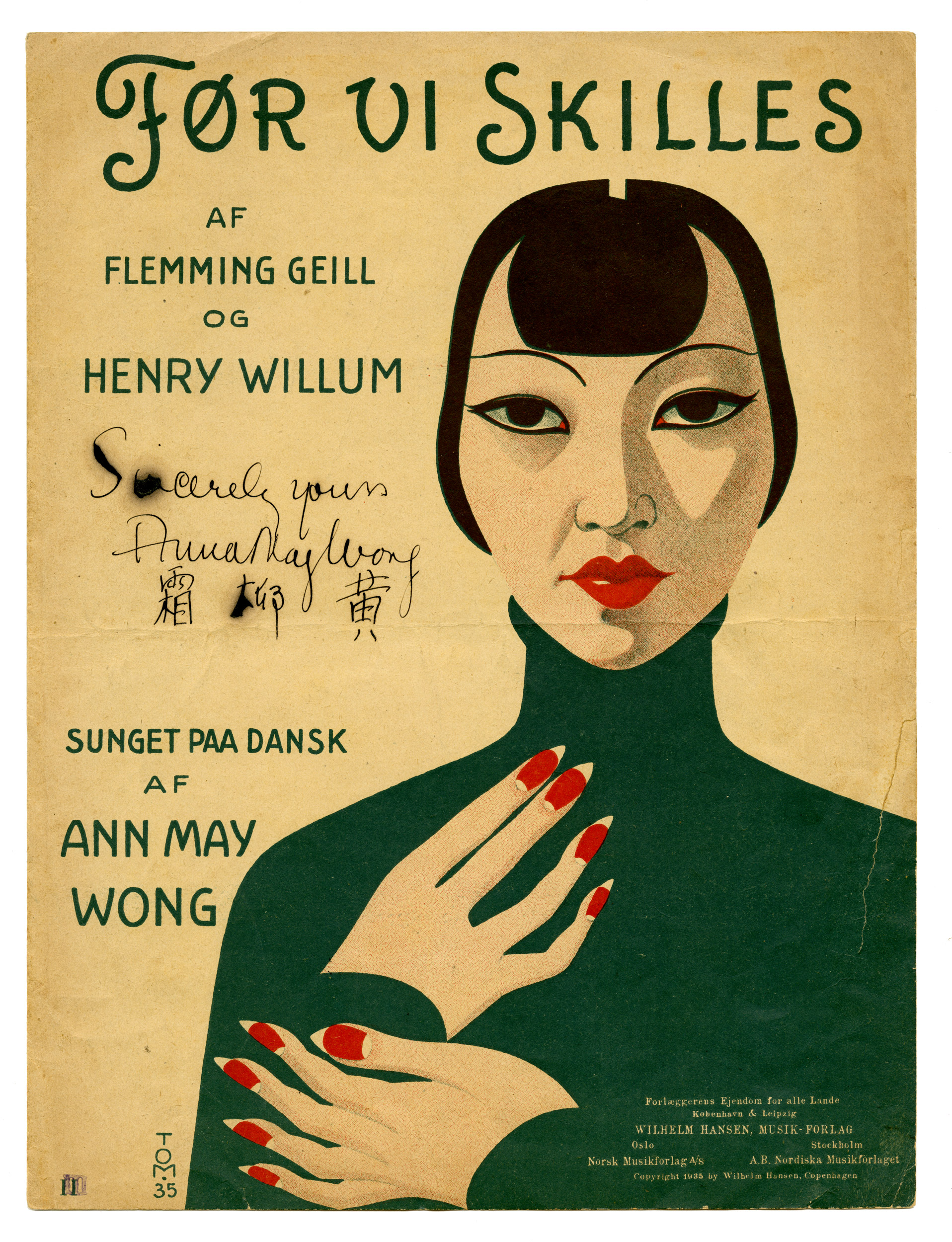

America has not always been the land of opportunity, however. One display in the exhibit chronicles the careers of African-American talents such as Josephine Baker and Paul Robeson who, along with such Asian American talents as Anna May Wong and Sessue Hayakawa, left to find greater acceptance in Europe. Although Robeson would eventually return, it wasn’t until 1988, the exhibit notes, that an Asian American play, David Henry Hwang’s “M. Butterfly,” would be produced on Broadway. It went on to win Tony Awards for best play and actor.

Josephine Baker became an international sensation as a singer and dancer at the Folies Bergère cabaret in Paris. She was famously outspoken on racial issues, refused to perform for segregated audiences, and eventually renounced her American citizenship as an act of protest.

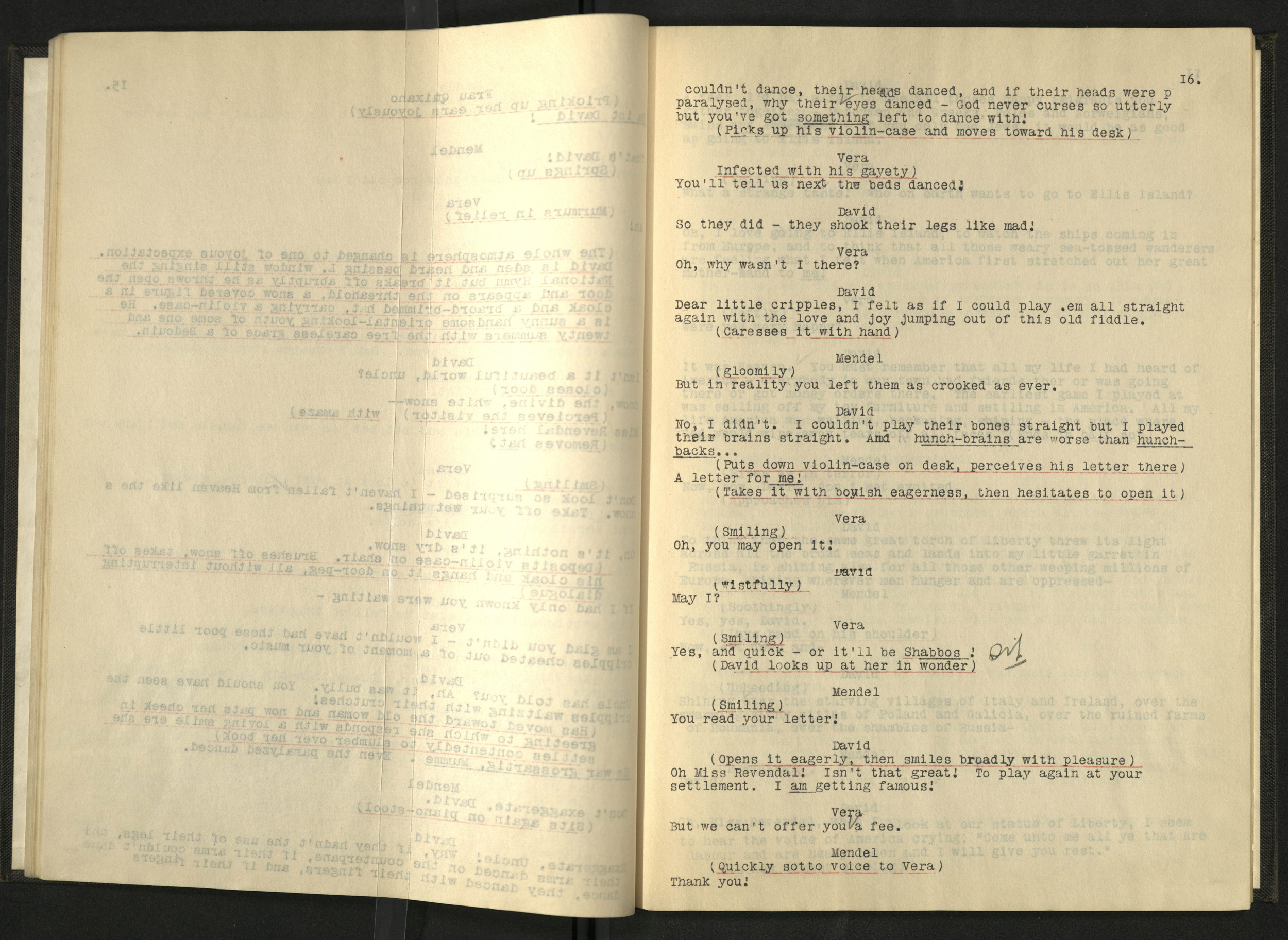

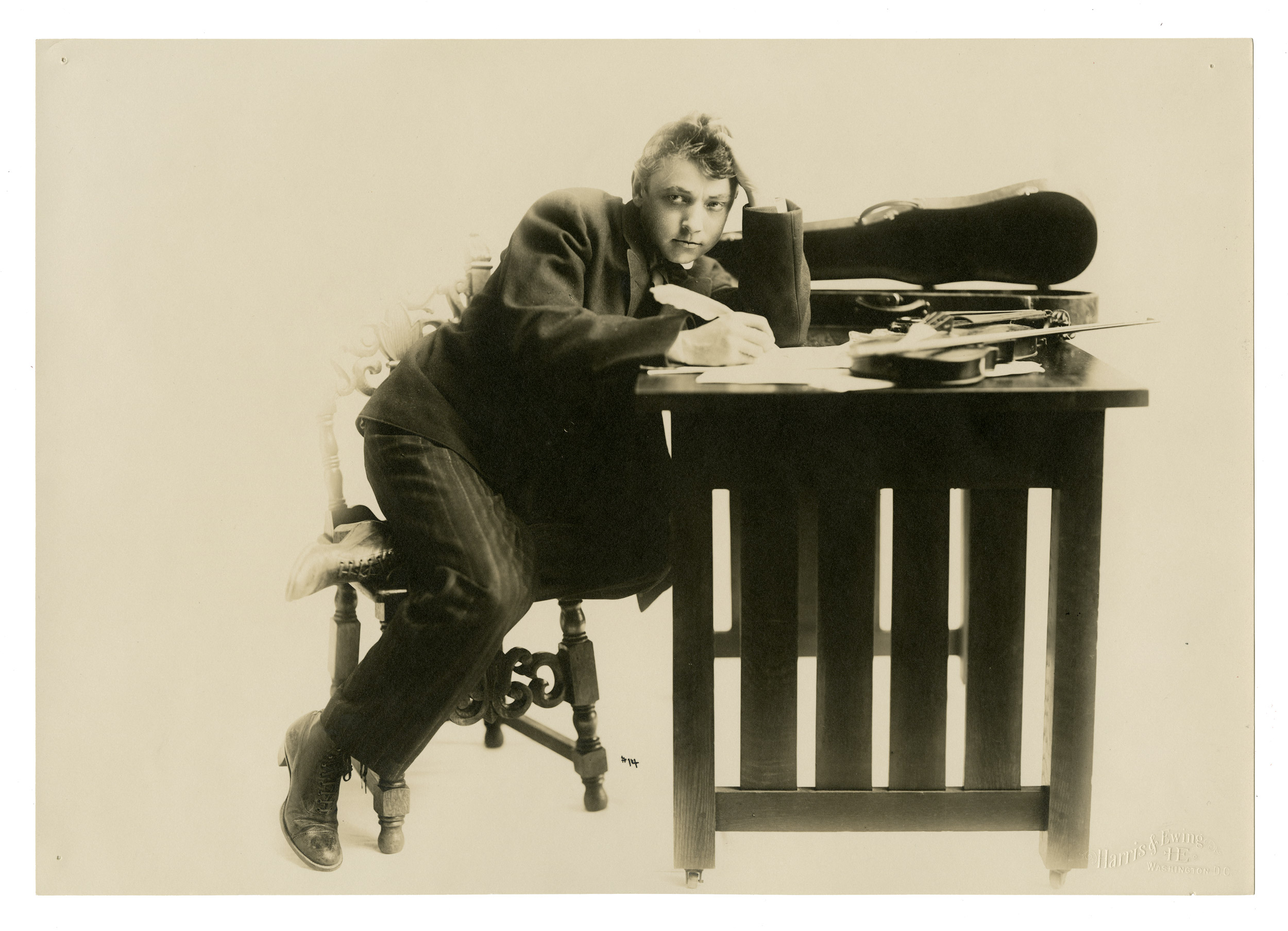

A metaphor for the immigration debate was popularized by Israel Zangwill’s 1908 play “The Melting Pot,” which centers on the struggle of a Russian Jewish protagonist named David Quixano to transcend his immigrant roots and to write a symphony that captures the promise of America; Walter Whiteside in “The Melting Pot,” 1908.

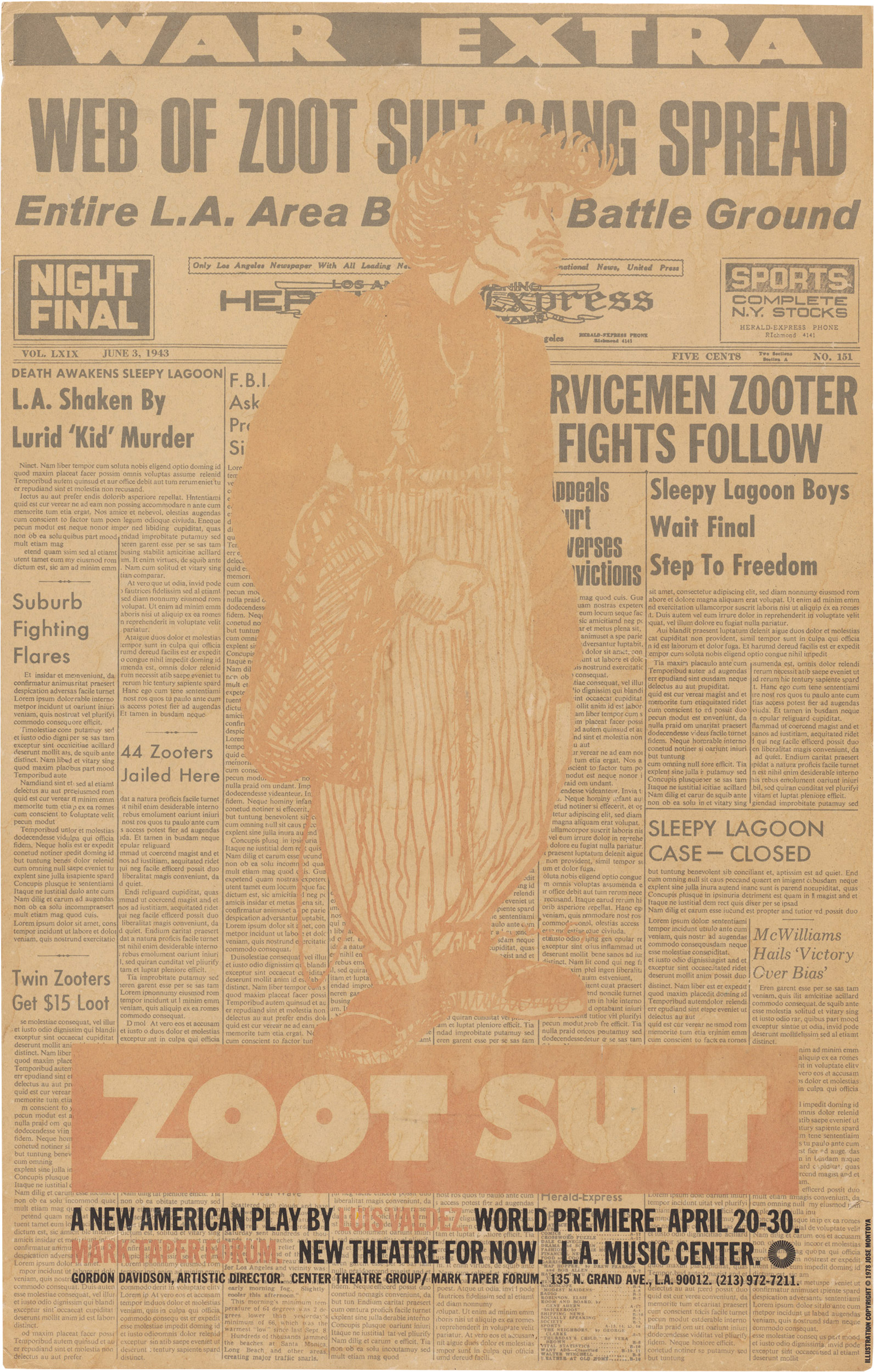

Luis Valdez’s pioneering Chicano play “Zoot Suit” (1978) earned national attention and paved the way for a generation of Latina and Latino theatermakers; Anna May Wong was a second-generation Chinese American actress who got her start in Hollywood during the 1920s but frustrated by typecasting and confined to stereotypical supporting parts, traveled to Europe, where she became a star on the stage and screen.

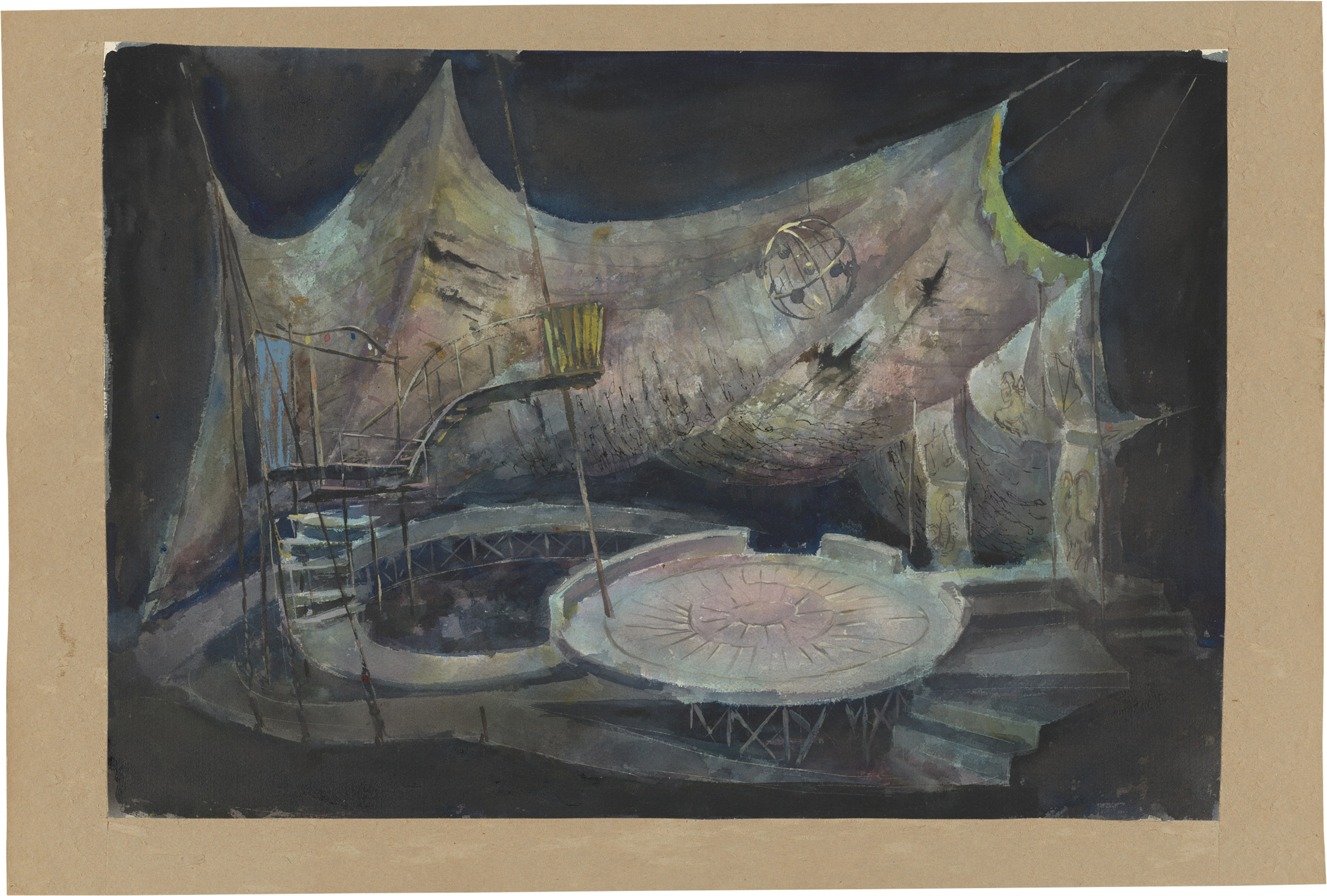

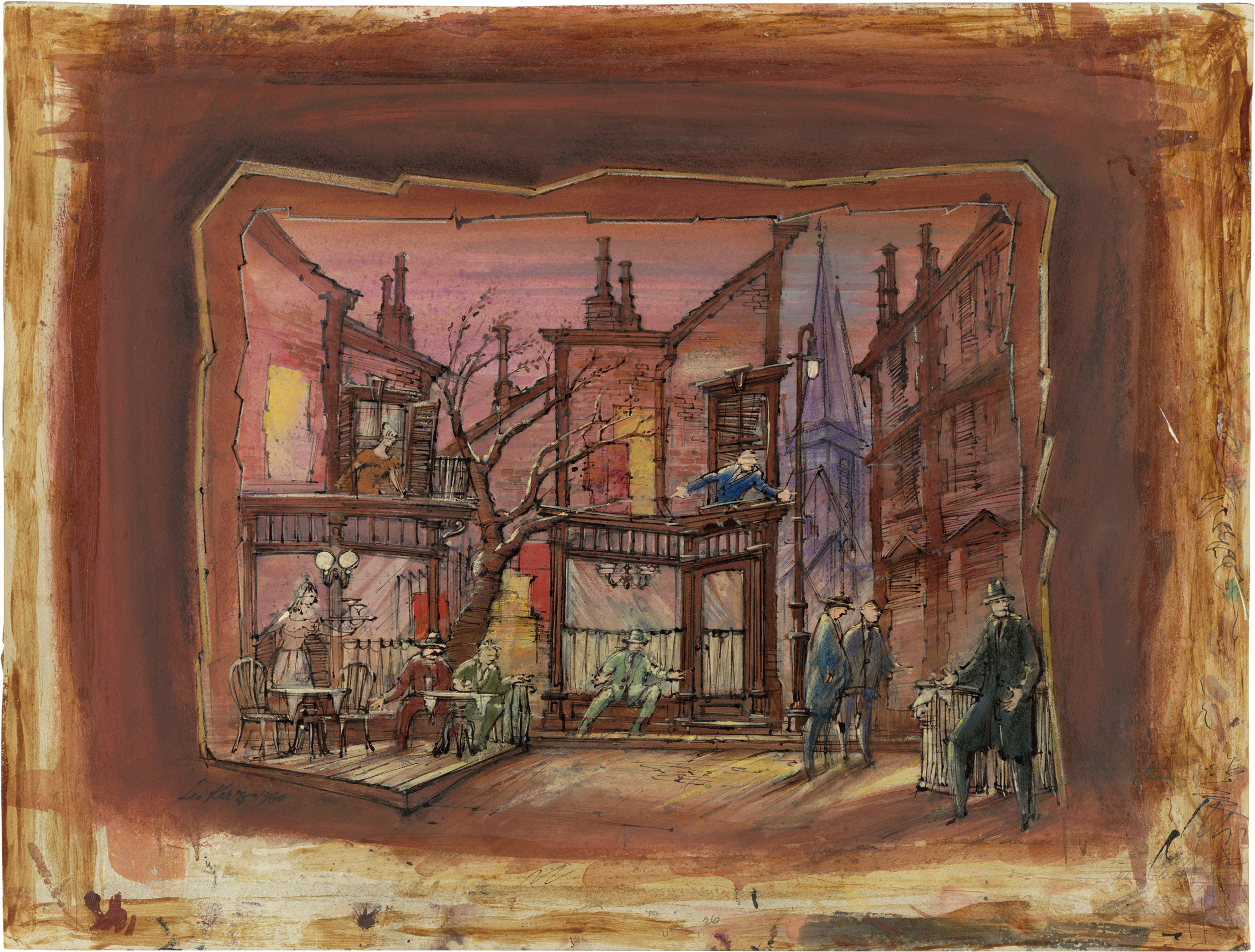

“Rhinoceros” set design by Leo Kerz, 1961; “J.B.” set design by Boris Aronson, 1958.

Images courtesy of Houghton Library

The exhibit ends on a hopeful note. A photo of B.D. Wong in his Tony-winning role from “M. Butterfly” graces the last case of the exhibit, along with a poster for “Zoot Suit” by playwright Luis Valdez.

With such riches on display, the message is clear. Immigrants “continuously revitalize American theater,” concludes Wittmann. “Whenever the door is open to a new group, they contribute.”

“Treading the Borders: Immigration and the American Stage” will be at the Houghton Library through Dec. 15.