Lecturer in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology Ian Wallace and his daughter, Lola, view the exhibit “Kalahari Perspectives: Anthropology, Photography, and the Marshall Family.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Anthropology with a family touch

Marshall photos from Africa in the 1950s, on view at Peabody Museum, capture a fading way of life in the Kalahari Desert

After loading the four huge vehicles with petrol drums, spare auto parts, barrels of water, crates of canned food, medicines, notebooks, rifles, film, and photographic equipment, the Cambridge, Massachusetts, couple, their two children, and an expedition team slowly caravanned into the desert. It was June 1951 — winter in South West Africa — and so cold that their blankets froze stiff in the night frost, so hot their radiators boiled over by day.

— Ilisa Barbash, “Where the Roads All End: Photography and Anthropology in the Kalahari” (Peabody Museum Press, 2016)

It was the second of eight expeditions by the Marshall family to the Kalahari region of what is now Namibia, and the start of a photographic experiment that became one of the most holistic efforts to document the cultures of Southwest Africa’s indigenous hunter-gatherers.

“The Marshalls were not the first to do this work, but they were the best,” says Peabody Museum curator of visual anthropology Ilisa Barbash. Her exhibition, “Kalahari Perspectives: Anthropology, Photography, and the Marshall Family,” which includes more than 40 images from the family’s expeditions, is on view at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology through March 31.

Sensing the hunter-gatherer way of life was on the verge of disappearing due to colonial expansion and Westernization, Laurence Marshall, a physicist and retired co-founder of Raytheon, proposed to the Peabody a comprehensive ethnographic study. His expeditions from 1950 to 1961 with his wife, Lorna, and their teenage children, Elizabeth and John, yielded 40,000 images that showed Ju/’hoan and /Gwi men, women, and children at work and play, revealing their culture as well as their humanity.

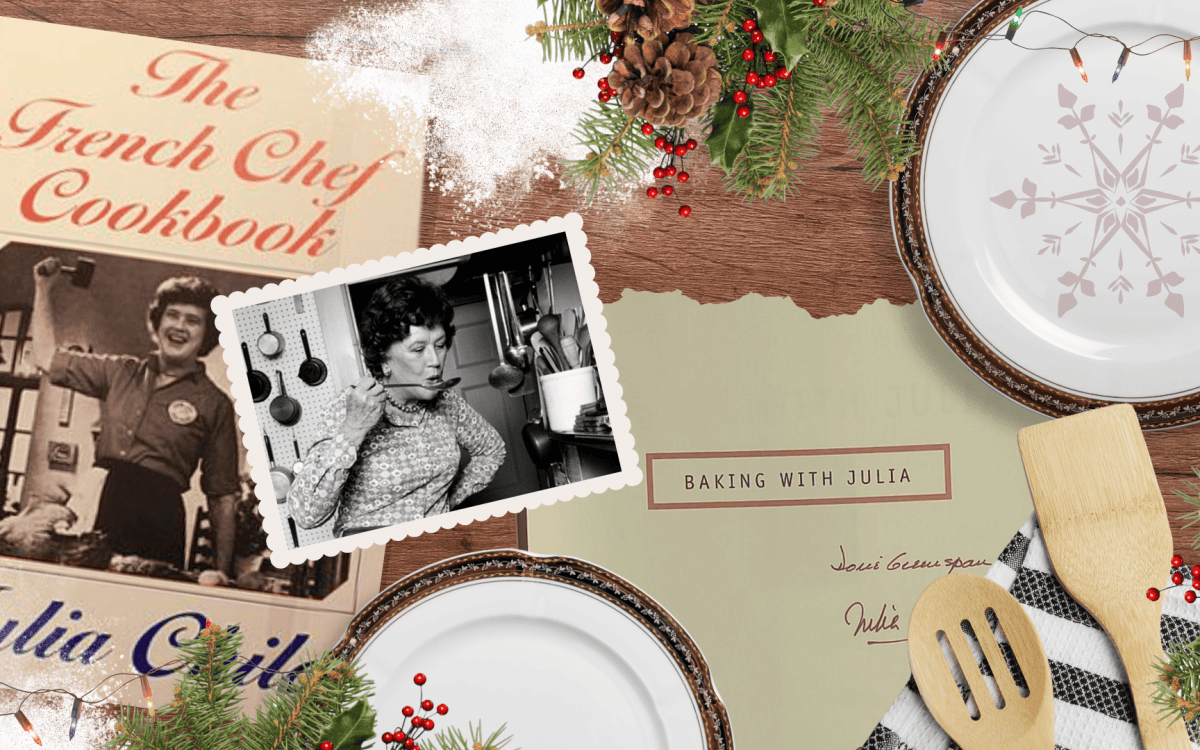

≠Toma, son of Khuan//a and Ga, hands a caterpillar to Elizabeth Marshall Thomas.

Photograph probably by Daniel Blitz, 1955; gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall; © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology (2001.29.641)

/Goishay balances firewood and her toddler, 1953. Dressed in traditional clothing, a young N!ai gives her half-brother /Gaishay a drink from an ostrich egg container, 1953.

Photographs probably by Anneliese Scherz; gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall; © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology (2001.29.373, 2001.29.257)

Previously, the groups then widely known as “bushmen,” a collective name for hunter-gatherer peoples now seen as pejorative, had been depicted as primitive, romantic, or exotic. As they got to know their subjects, the Marshalls’ images became ever more dynamic and intimate, with the Ju/’hoansi appearing as individuals rather than as anthropological specimens.

The Peabody exhibit also features two new visual projects about contemporary Kalahari peoples. In addition, the museum will screen John Marshall’s documentary film “N!ai, the Story of a !Kung Woman” at 6 p.m. Oct. 11 followed by a panel discussion.

Elizabeth Marshall and Daniel Blitz, a photographer from a 1955 expedition, attend the Peabody exhibit’s opening.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Ilisa Barbash.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“The Marshalls planned a pure study that could be used then and in the future,” Barbash said. “And this is amazing — they learned on the fly. None of them had formal training in film or anthropology. Fortunately, Laurence Marshall was such a good organizer that he was able to keep his family alive in the desert, by calculating how much water was needed, and figuring out where to leave gas cans in the Kalahari.”

TsamKxao ≠Toma, ≠Toma’s son, with his homemade clay “camera,” 1955. TsamKxao ≠Toma later became a community leader and is pictured below in 2017.

Photograph probably by Daniel Blitz; gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall; © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology (2001.29.657)

Chief Bobo (TsamKxao ≠Toma, pictured as a boy above) discusses new heritage projects, Tsumkwe, 2017.

Photograph by Stef Ndumba, !Xun, Platfontein, South Africa; courtesy of Chris Low of Thinking Threads and the !Khwa ttu San Heritage Centre

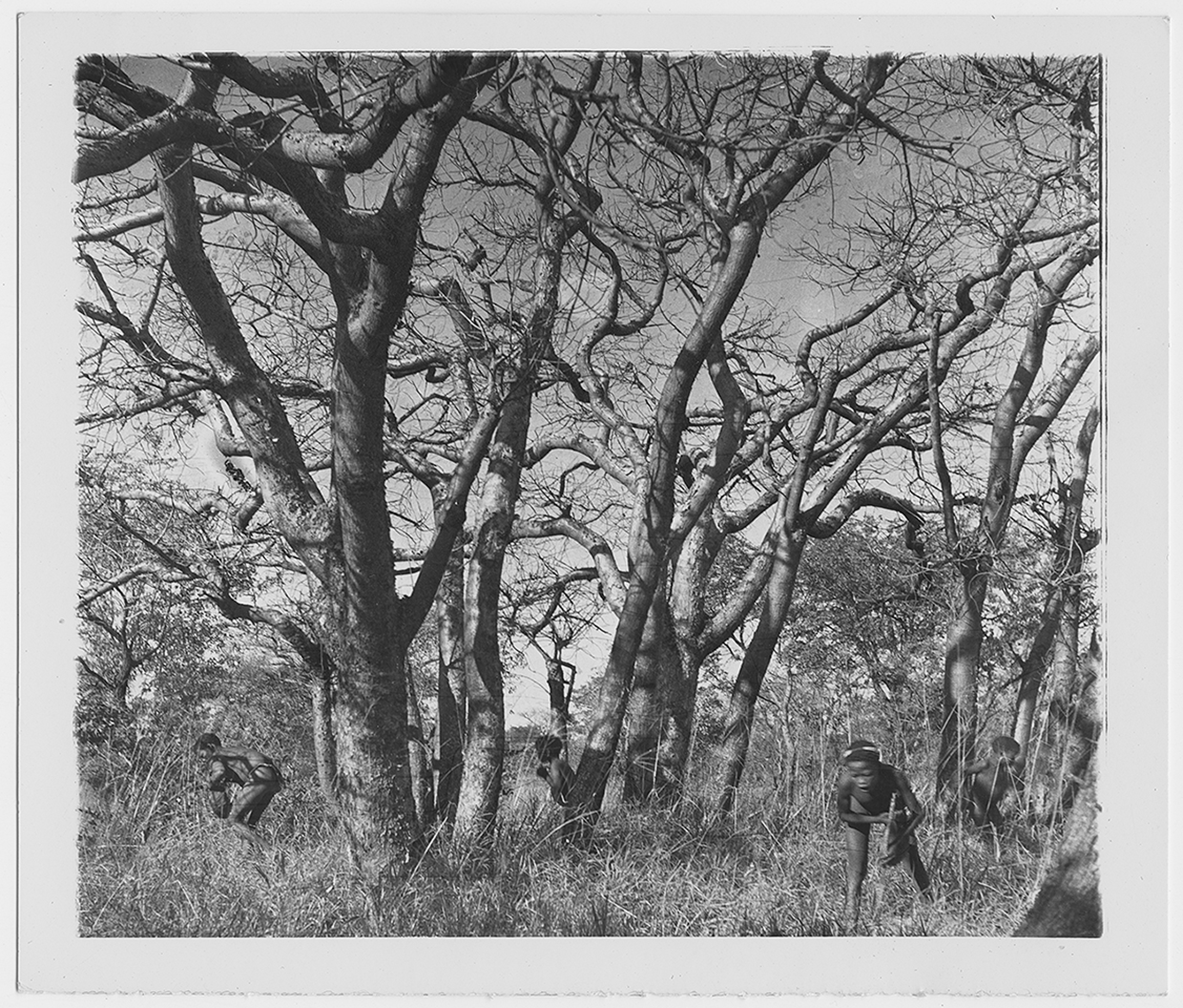

N!ai washing her clothes at the edge of the Gautscha Pan, 1957‒58. Ju/’hoan boys gather mangetti nuts seen through interlacing trees, 1953.

Image 1 probably by Robert Gesteland, Image 2 probably by Anneliese Scherz; gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall; © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology (2001.29.15526, 2001.29.735)

Ju/’hoansi walk in a line across the desert, 1952‒53.

Probably Laurence, Lorna, or John Marshall; gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall; © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology (2001.29.390)

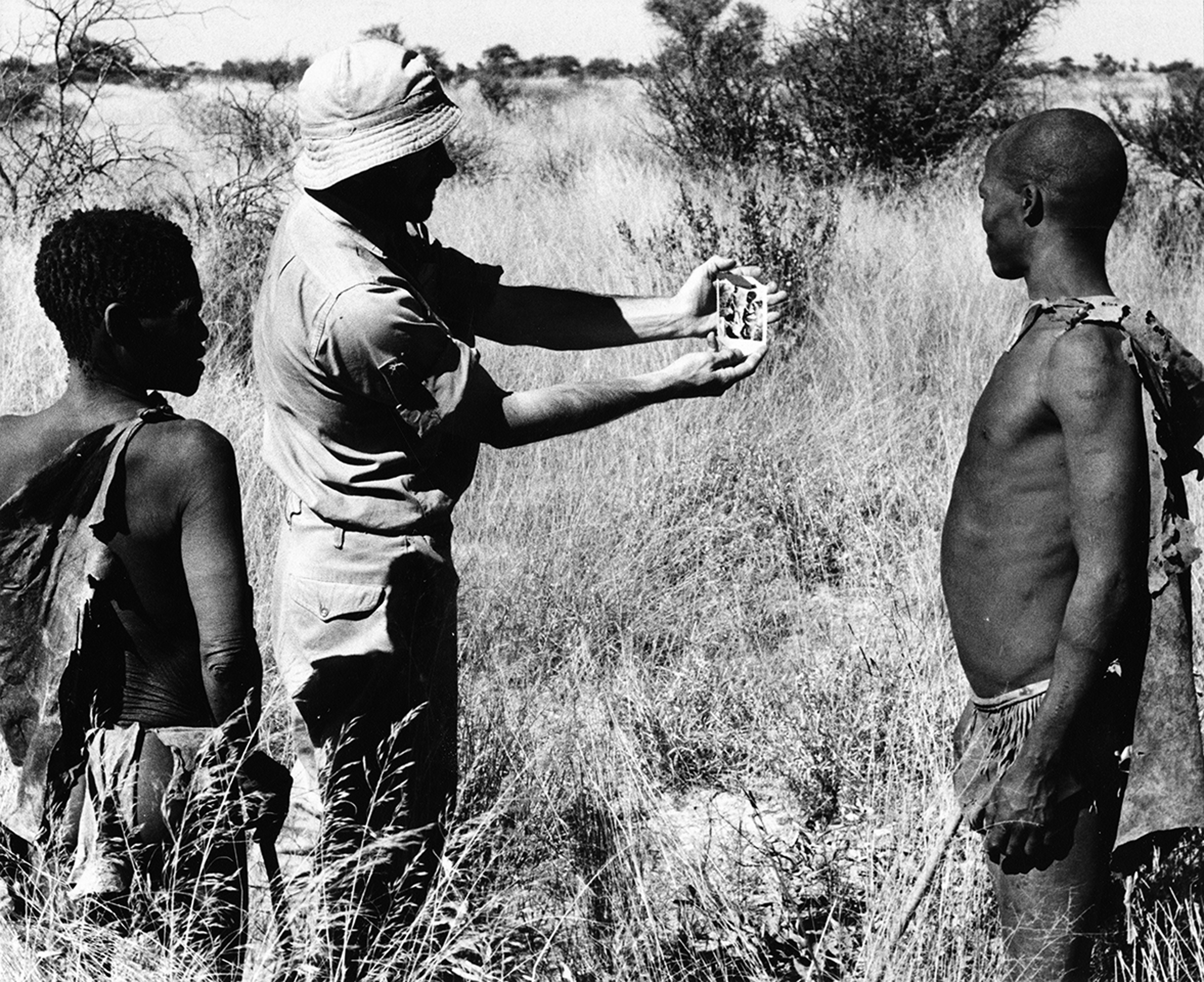

Botanist Bob Story shows Polaroid picture to Oukwane and !Gai, 1955. N!ai (left) and friends pose beside one of the Peabody Museum’s expedition trucks in 1955.

Photographs probably by Daniel Blitz; gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall; © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology (2001.29.268, 2001.29.579)

Laurence Kennedy Marshall speaking with Xama at /Gam, 1955.

Photograph probably by Daniel Blitz; gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall; © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology (2001.29.620)