Illustrations by Scott McCloud; video by Kevin Grady/Radcliffe Institute

The serious business of comics

Scott McCloud explains how they can promote a new way of seeing

The world is full of visual stimuli. And the way we experience them isn’t just the stuff of comic book art, but the essence of life itself, according to Scott McCloud. The locally rooted comic artist and theorist, well-known for his 1993 book “Understanding Comics,” drew a capacity house to the Knafel Center for a talk on “Visual Storytelling, Visual Communication.”

Presented by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, the talk was introduced by Tomiko Brown-Nagin, dean of the Institute, and was followed by a discussion with Shigehisa Kuriyama, the faculty director of the institute’s humanities program and a confirmed fan. McCloud’s talk referenced his books and a popular TED talk, but went beyond the comics format to examine the nature of visual perception. Illustrated with a fast-moving backdrop of nearly 300 slides, Thursday afternoon’s talk was by turns whimsical, philosophical, and hilarious.

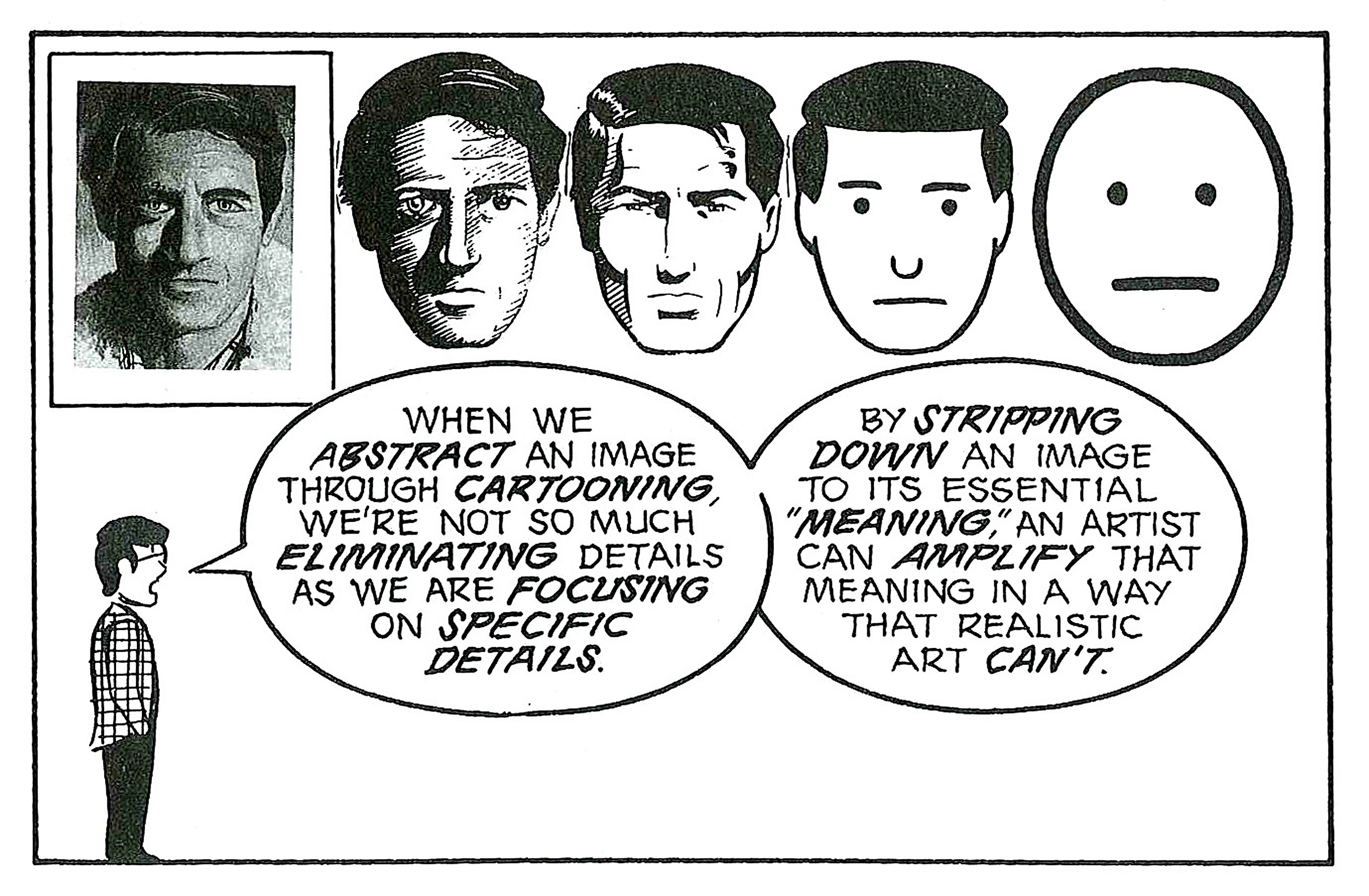

“Visual communication is a two-way street: We all meet the artist halfway,” McCloud said. He began by recalling his childhood in Lexington, Mass., and his roots as an artist. “When I grew up in Lexington, drawing robots and spaceships and later superheroes, I was hoping someone could figure out what was going on in every panel,” he said. “Then when I went to Syracuse as an art student, I found out that visual artists don’t always trust the idea of pictures sending messages. We expect it to be more inscrutable somehow, maybe even beyond meaning. But every picture is still saying something.”

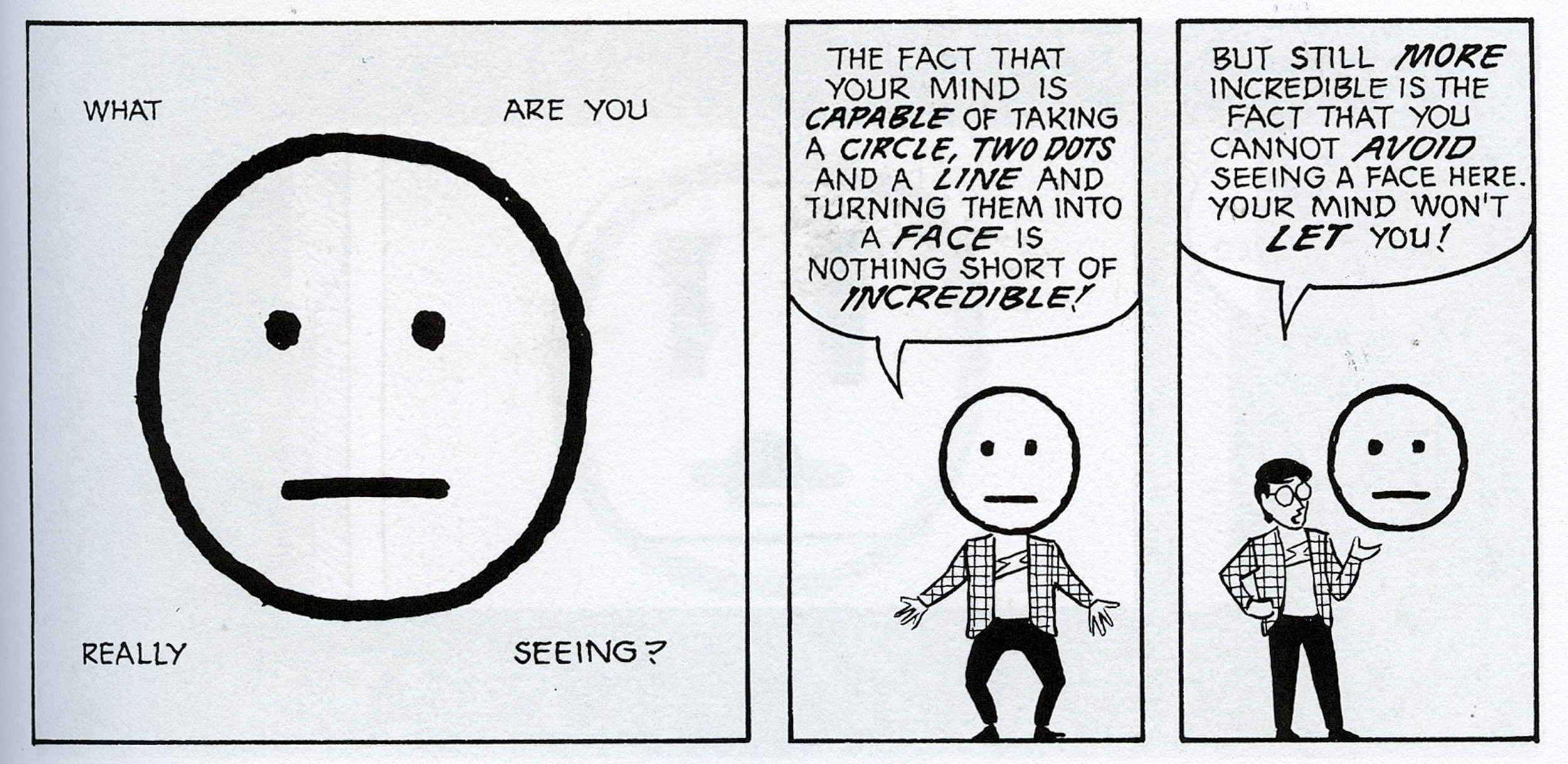

McCloud’s central point was that there are no neutral visual decisions: Every visual display we see is meant to communicate something, and every artist who creates one has a specific intention. To illustrate this, he demonstrated how people tend to organize images into certain patterns. He began with the most basic of images, a straight line and two dashes. If the dashes are moved above the line, we’re likely to see them as eyes and a mouth, a human face.

“Pattern-finding is a basic human capability that we depend on for our survival, and that a cartoonist also depends on.”

Scott McCloud

Panels from “Understanding Comics.”

Courtesy of Scott McCloud

“We are animals, and it is our tendency to find ourselves in everything we see,” McCloud said. “This is how we survive as a species … Pattern-finding is a basic human capability that we depend on for our survival, and that a cartoonist also depends on.”

To show how people create these patterns, he screened a photo of a church in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., with two oval windows sitting above a triangle-shaped ledge. And he noted, correctly, to judge from the laughs in response, that most were seeing it as the face of a “confused chicken.”

Sometimes the wrong visual decisions have consequences, he said. He pointed to something most people have seen in hotels: the diagram reading, “In case of fire use stairs, do not use elevator.” The standard version, he noted, is “a masterpiece of incoherence.” There’s an overlarge stick man who appears to be running toward the fire, and a couple who appear to be getting fished out of an elevator with chopsticks. With a few simple tweaks, he demonstrated, the diagram could be made not only more pleasing visually, but clearer and more functional.

Scott McCloud speaks at Radcliffe’s Knafel Center.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The good news, he said, is that even non-artists are now more inclined to communicate visually, with the popularity of emojis as an example. This in turn prompts people to consider the messages they send in face-to-face communication. “This is what it is to be alive,” he told Kuriyama during a Q&A session after the talk. “Look at what your body is doing to send these messages. That is fundamental; it should be a part of basic education. Also, it is so much fun.”

In a new postscript to his talk, McCloud described a vivid visual experience, a drive that he took with his wife and daughter, Sky, to view last year’s solar eclipse. Like McCloud’s father, Sky is partially blind, and thus has a different experience of the world.

“We all build models out of whatever our senses can give us. She has extreme light sensitivity, and sunlight is not fun for her, so she learns how to get the gist of a scene from split-second exposure.” The eclipse itself, he said, was a wondrous example of how nature creates symmetry. “We know that the sun and the moon are not the same size, we know that they are nowhere near each other and nowhere near us. Yet they keep trying to convince us otherwise. So you have to ask, did we really come to see the sky today, or did the sky come to see us?”