Harvard file photo

Radcliffe scholar tracks squirrels in search of memory gains

Neuroscientist homes in on hippocampal plasticity

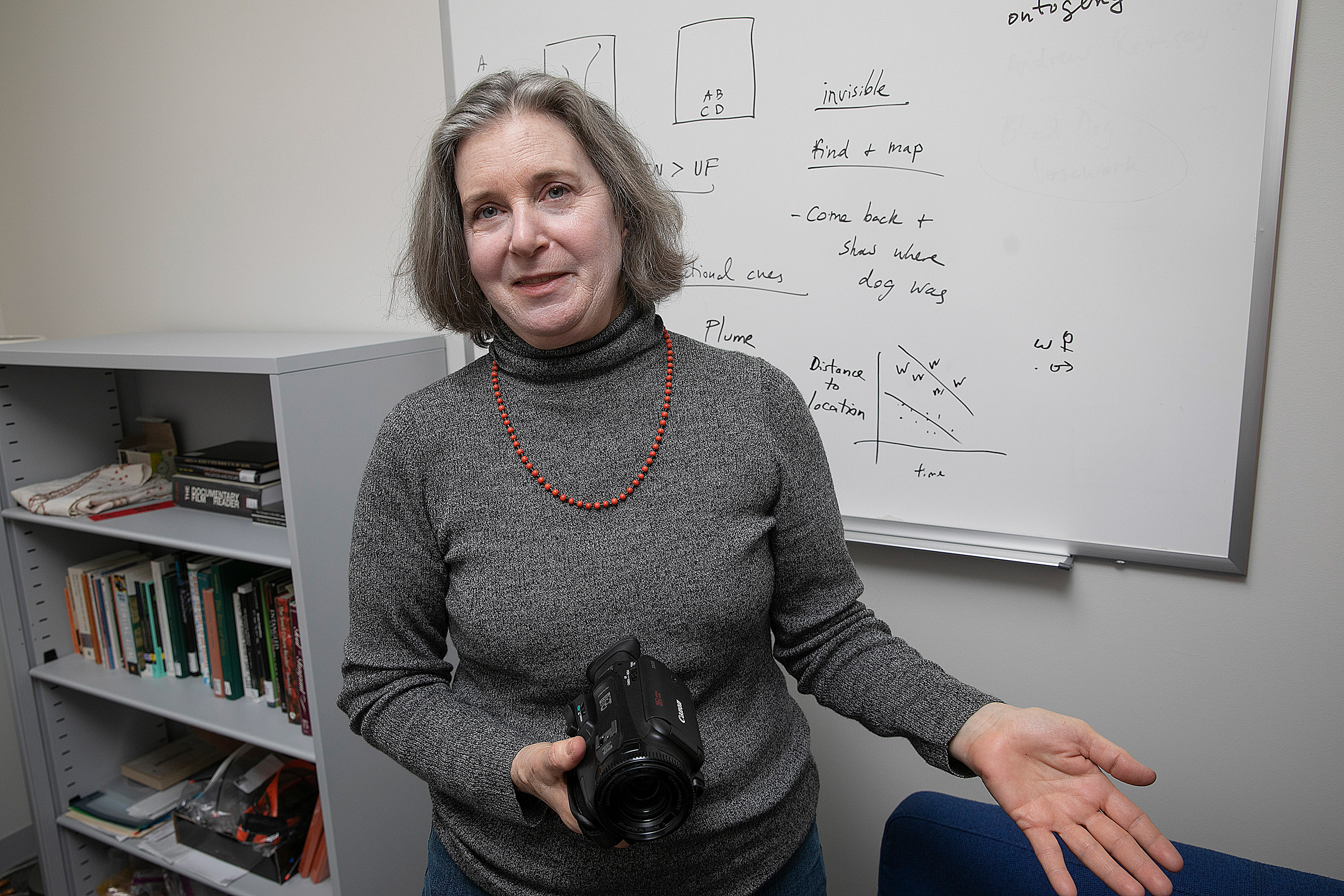

Lucia Jacobs, a professor in the Psychology Department and the Helen Wills Institute of Neuroscience at the University of California, Berkeley, will spend part of her time as a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study exploring squirrel brains. Jacobs is particularly interested in how the animals cache and retrieve their food and what happens in the memory-associated hippocampus during that process.

“Hippocampal plasticity is critical for human memory,” she says, “so there could be something interesting to learn there from squirrels.”

Q&A

Lucia Jacobs

GAZETTE: How did you get interested in studying squirrels?

JACOBS: Squirrels have always fascinated me; I especially remember racing every Easter morning to get to the chocolate eggs before the squirrels did. But I became interested scientifically in their foraging behavior when I started graduate school at Princeton. I was interested in behavioral ecology and how animals make foraging decisions, and gray squirrel foraging was particularly complex because of their food-caching decisions. Initially, I was going to compare squirrels that stored food in different spatial patterns — clumped versus scattered — but I ended up focusing only on the gray squirrel, the scatter-hoarding species. The first thing I did was show that squirrels remember where they bury their nuts. That got me interested in memory — the hippocampus and how spatial cognition is adapted to a species’ environment — a question I am still pursuing.

GAZETTE: What will your Radcliffe work involve?

JACOBS: I am part of a multi-university research initiative that is a collaboration between engineers and biologists to, among other things, look at the problem of spatial cognition in squirrels from a developmental point of view by looking at orphaned baby squirrels. We study human developmental cognition as a way of understanding the adult: Where does language come from? Where does math come from? So, with these baby squirrels we can understand spatial cognition and caching decisions by learning how they develop. In adults, the behavior is rational. They know exactly what they are doing; it’s very precise. The question is how much of that did they come with? We really don’t know. It’s a very complicated thing they have to do when they cache and then retrieve the nuts they’ve hidden.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

“There may be simple ways that squirrels are organizing their lives that help them remember that you might be able to translate to a person with Alzheimer’s.”

Lucia Jacobs, pictured above

GAZETTE: Some of your work involves economic decisions squirrels make. Can you describe what those are?

JACOBS: Squirrels want to minimize their risk-return ratio. There are three risks: you cache the nut and you forget it; you cache it and while you are retrieving it you get eaten by a predator because you are out in the open looking for nuts; or someone else steals it. How do you minimize these things? Our studies show that to minimize the pilfer risk, squirrels are very careful about where they place their caches. They measure the nut and then they carry it a distance that is proportionate to the value of the nut. The better the nut, the more care they take to put it in a safe place, buried really well to minimize the pilfer risk. That’s going to increase their predation risk while they are doing it, and that’s probably going into their calculations. Then you have to remember where it is.

Our work has shown that the squirrels organize their caches by nut type. In human memory this is known as chunking. If you are given a random list of 10 things to remember and five are car types and five are kinds of furniture, you will remember them and you will repeat them back as the five cars and the five types of furniture. This is called chunking, and it is one way we increase our memory capacity. Squirrels use spatial chunking. In one study we gave squirrels four different types of nuts and we found statistically they would segregate the nuts by type. Based on everything we know from cognitive science, it’s more of an effort to do it, but it makes their locations easier to remember.

GAZETTE: What can this work help you learn about the human brain?

JACOBS: Our past work focused on the squirrel hippocampus, which is a key part of the brain we lose in Alzheimer’s. What we’ve found in our research is that part of the hippocampus increases in male squirrels specifically during the caching season in the fall; it’s not new neurons, but it’s showing this seasonal plasticity. Part of the hippocampus in males is the part that we’ve proposed underlies how females code the location of objects. So basically, we speculate that males have to start thinking like females in the fall when they’re hiding all these nuts, which is why their hippocampus changes. Hippocampal plasticity is critical for human memory, so there could be something interesting to learn there from squirrels.

The real progress in Alzheimer’s research is being done at the cellular level. But in terms of how to manage the quality of life for a patient, we might learn something from mnemonics that squirrels are using. There may be simple ways that squirrels are organizing their lives that help them remember that you might be able to translate to a person with Alzheimer’s.