Detail of “Design for a Multimedia Trade Fair Booth,” Herbert Bayer, 1924.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard: America’s Bauhaus home

Exhibit showcases the long reach of the influential art movement as it celebrates centennial

A hundred years later, the Bauhaus is everywhere.

Much of today’s “mod” furniture — from teak and tubular tables to simple yet graceful sofas to chairs and lamps that blend form and function — has its origins in the Bauhaus, the 20th century German modern art/crafts and design school turned major cultural movement.

Similarly, the open floor plan embraced by millions of homeowners is rooted in the Bauhaus approach to architecture, one that rejected decorative details in favor of functional design, smooth and flat surfaces, sharp angles, and cubic shapes.

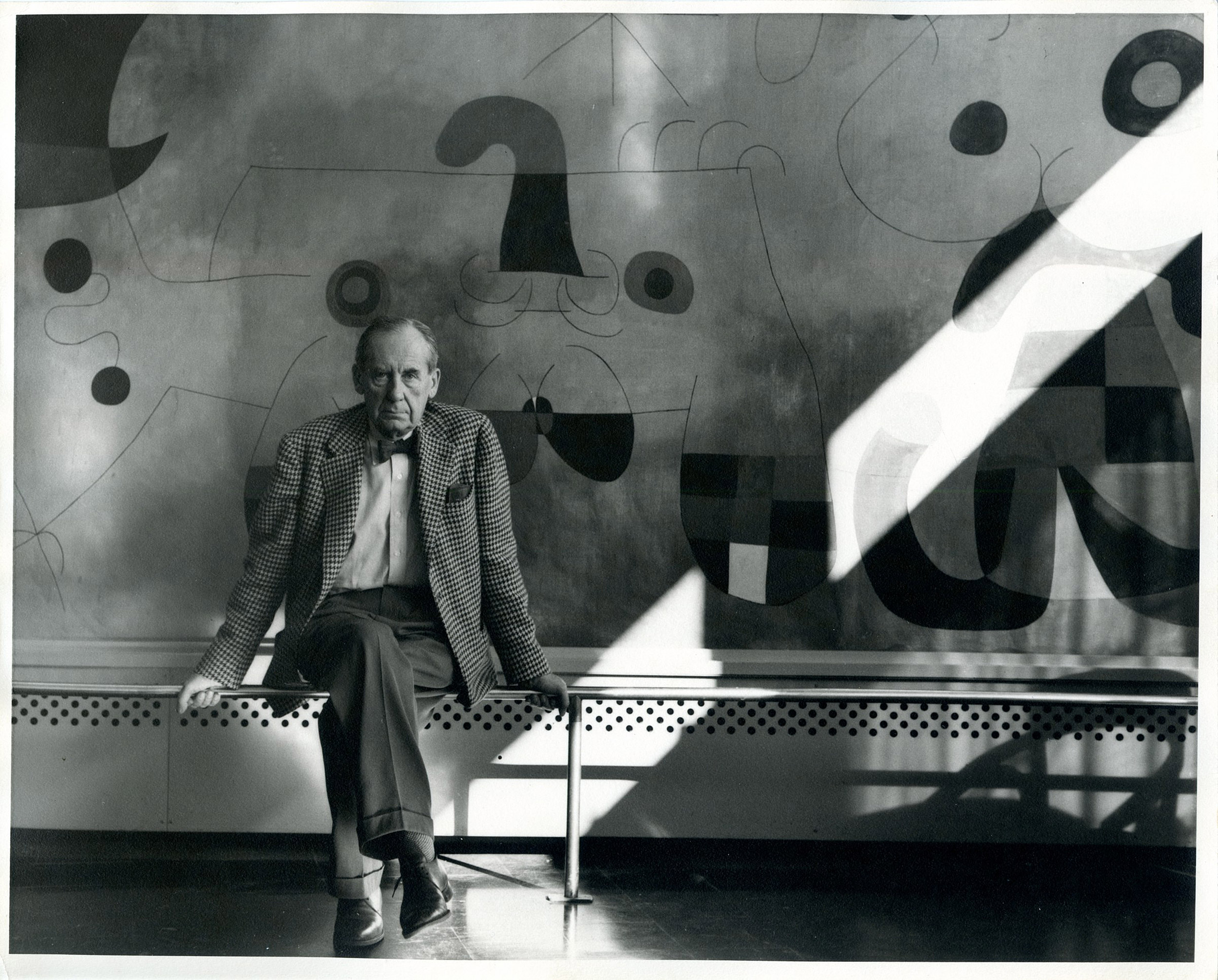

Portrait of Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius with Joan Miro mural at Harvard’s Graduate Center.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

The movement can even be found in the current KonMari craze that encourages people to declutter their lives. For Bauhaus architects and designers, a happy home was one that was deceptively simple and highly organized.

The founder of Bauhaus was Walter Gropius, a Prussian architect who hoped his experimental school would “bring together all creative effort into one whole, to reunify all the disciplines of practical art — sculpture, painting, handicrafts, and crafts — as inseparable components of a new architecture.” Gropius succeeded spectacularly, setting a modern current in motion.

He eventually moved to the U.S. and taught for many years at Harvard, ensuring that the University would have its first modern building, as well as one of the most comprehensive Bauhaus collections in the world.

Beginning Friday and running through July, much of that collection will be on display. Visitors to the Harvard Art Museums’ third floor will find a trove of Bauhaus productions, including photographs, student exercises, textiles, topography, iconic design objects, and archival ephemera as part of “The Bauhaus and Harvard,” an exhibition timed to the centennial of the school’s founding.

![Marianne Brandt, Untitled [with Anna May Wong], 1929.](https://dev.news.harvard.edu/gazette/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/011719_Bauhaus_202_2500.jpg)

(left) Marianne Brandt, “Untitled [with Anna May Wong],” details, 1929. (right) “Design for a Rug,” details, Anni Albers, 1927.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer; images @ President and Fellows of Harvard College

“There is so much diversity there. It’s not one style, it’s not one artist, it’s not one material. It’s just this incredible creativity and innovation in so many different areas,” said Laura Muir, research curator for academic and public programs and former assistant curator of Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, who organized the new exhibition. The show features nearly 200 works drawn almost entirely from the Busch-Reisinger’s extensive Bauhaus holdings and explores three themes: the objects made at the Bauhaus in Germany; Bauhaus teaching in the U.S.; and the Bauhaus at Harvard’s Graduate Center.

Gropius’ experimental school emerged amid the cultural flourishing of Weimar Germany and embraced the utopian ideal that great design could change the world. First located in Weimar, then in Dessau, and finally in Berlin, the Bauhaus brought together artists and craftspeople, designers and architects on residential campuses offering workshops, organized by materials, where the participants explored new ways to create and teach.

In the museums’ first gallery, a series of exercises from the school’s preliminary course, a requirement that introduced enrollees to basic design and color theory, reminds viewers “that the Bauhaus was first and foremost a school,” said Muir.

Other items in the show demonstrate how students and their instructors routinely pushed artistic boundaries. Hungarian architect and designer Marcel Breuer created his Club Chair (B3), or Wassily Chair, a blend of fabric and tubular steel that was inspired by his curved bicycle handlebars, while he was a student at the school in 1925. The work became the blueprint for countless contemporary designs and underscored the movement’s embrace of a lean aesthetic and modern materials. Eventually, Breuer became an instructor at the school’s furniture workshop.

Laura Muir, research curator for academic and public programs and former assistant curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, organized “The Bauhaus and Harvard.” In the foreground is “Construction in Sheet Metal,” Hannes Beckmann, 1950, @ President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The Bauhaus’ experimental ethos is also exemplified in László Moholy-Nagy’s electrically powered swirling kinetic sculpture of metal, glass, and plastic titled “Light Prop for an Electric Stage.” A seminal work in the history of 20th-century sculpture, it was designed to cast shadows, colors, and patterns on an adjacent wall as its moving perforated discs and screens interacted with a beam of light. Intended to be mass produced for use in theaters, the piece was a revolutionary mix of art and technology when it debuted in a Paris exhibition in 1930. At one point, Gropius aptly described Moholy-Nagy as an artist who “ventured into ever-newer experiments with the curiosity of a scientist.”

Important figures in the field

While Moholy-Nagy and artists Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee are some of the names most often associated with the movement, the exhibit also highlights a range of less-recognized but prodigiously talented creators, designers, and instructors at the Bauhaus, many of them women. “We wanted to show the breadth and depth of the collection and foreground some of these lesser-known figures and their contributions,” said Muir.

One of those figures was Lucia Moholy, whose evocative black-and-white photograph “Bauhaus Masters’ Housing, Dessau, 1925-1926: Lucia Moholy and László Moholy-Nagy’s Living Room,” was, like many of her images, a sophisticated work of art and a polished promotional tool. “Through her photographs, the Bauhaus was constructing its image,” said Muir, “crafting a vision of modern living, something that was clean, uncluttered, and meant less work for the housewife.”

Marcel Breuer’s “Club Chair.”

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

Once students completed the introductory course, they joined one of the Bauhaus workshops, with women typically assigned to weaving. The resulting work was exceptional but not fully recognized until the Bauhaus shifted its focus from crafting one-of-a-kind pieces to creating prototypes for mass production, making the weaving workshops some of the most successful at the school. Textile artist and printmaker Anni Albers, who was fascinated with a fabric’s role and appearance, was a driver of that success. Samples of her wall coverings and other material on view point to her interest in experimenting with unconventional materials such as cellophane and twisted paper.

Another Bauhaus weaver, Otti Berger, became a sought-after designer of fabrics. She was first a student and later a teacher at the Bauhaus, and a swatch of her handweaving highlights her experimenting with patterns. “She was incredibly talented and successful at the time, and one of the few people who received patents for her work,” said Muir. But Berger’s blossoming career was cut short when she was murdered in the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1944.

Study for “Verdure,” Herbert Bayer, 1950.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Buildings at Harvard

The Bauhaus’ ties to Harvard are concrete, literally. After the German school closed in 1933, Gropius moved to America, where he became a professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. While there, he encouraged many of his Bauhaus colleagues to join him. He also collaborated with Busch-Reisinger curator Charles L. Kuhn to establish an archive at the museum, laying the groundwork for the museums’ collection.

Gropius also founded The Architects Collaborative, an architectural based firm in Cambridge that designed the Harvard Graduate Center in 1950, the first modern building on Harvard’s campus. The structure at Harvard Law School was renamed the Caspersen Center, a cluster of simple, flat-roofed, sleek dormitories of steel and concrete arranged around a small courtyard.

Gropius wanted the building to mimic the “quadrangle structure so central to the Harvard tradition, but in a very modernist language,” said Muir. Gropius also wanted the building to incorporate contemporary art and pushed for a budget that would cover the cost of such art there.

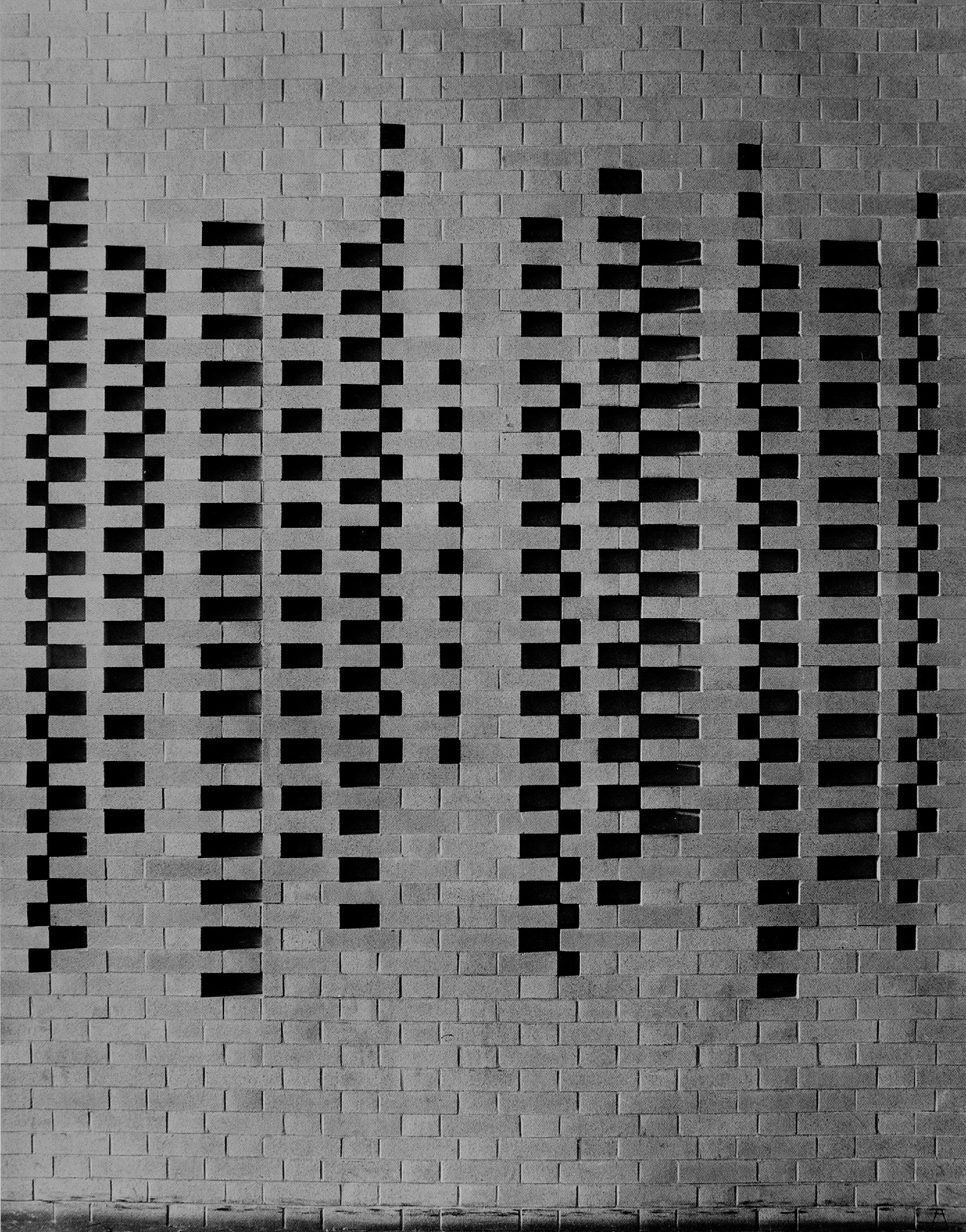

Today, visitors to the Caspersen Center will find a floor-to-ceiling relief of yellow masonry brick called “America” (1950) by Bauhaus contemporary Josef Albers integrated into the wall of the building’s Harkness Commons fireplace. A photograph of the work, a modern construction inspired by the pre-Columbian Mitla ruins in Mexico, is on view in the show.

An adjoining gallery on the museums’ third floor contains “Hans Arp’s Constellations II,” another of the site-specific works commissioned for the Graduate Center, consisting of a 13-panel wall relief. The artist turned graphic designer Herbert Bayer’s massive oil-on-canvas abstraction titled “Verdure,” which once hung in the Harkness dining room, is one of the most striking works in the exhibit. Too big to fit in the museums’ freight elevators, the piece, which measures 6 feet by 20 feet, was hoisted up through the stairwell to the third floor.

“It’s among the many works people will be surprised by” said Muir.

(left) South facing view of the Harvard Graduate Center main quadrangle with the World Tree sculpture by Richard Lippold and partial exterior of Harkness Commons in the foreground. (right) “America,” Josef Albers, brick relief, 1950.

Harvard Law School Library, Historical & Special Collections; Harvard University Archives

But much smaller, more discrete works that highlight the modernist movement’s influence in the U.S. also surprise. Desperate to escape Nazi Germany, many Bauhaus artists fled to America in the 1930s and ’40s and became instructors at colleges around the country, where they taught a new generation to experiment with art, architecture, design, and technology. (Moholy-Nagy famously brought the movement to Chicago, creating the New Bauhaus in 1937. The school still exists as the IIT Institute of Design.)

One of the final galleries shows exercises, produced in the 1940s by students studying with Bauhaus teachers at Brooklyn College, Newcomb College, and Black Mountain College, that illustrate the movement’s lasting reach and impact. A series of paper sculptures in a vitrine produced by the students of Newcomb College’s art school dean Robert D. Field (who worked at Harvard and trained with Gropius), highlight the Bauhaus embrace of simple geometric shapes and materials.

The studies, in addition to being “so beautiful in and of themselves,” said Muir, “truly document the spread of Bauhaus in America.”

Click here for a list of events related to the Bauhaus centennial that are happening across Harvard.