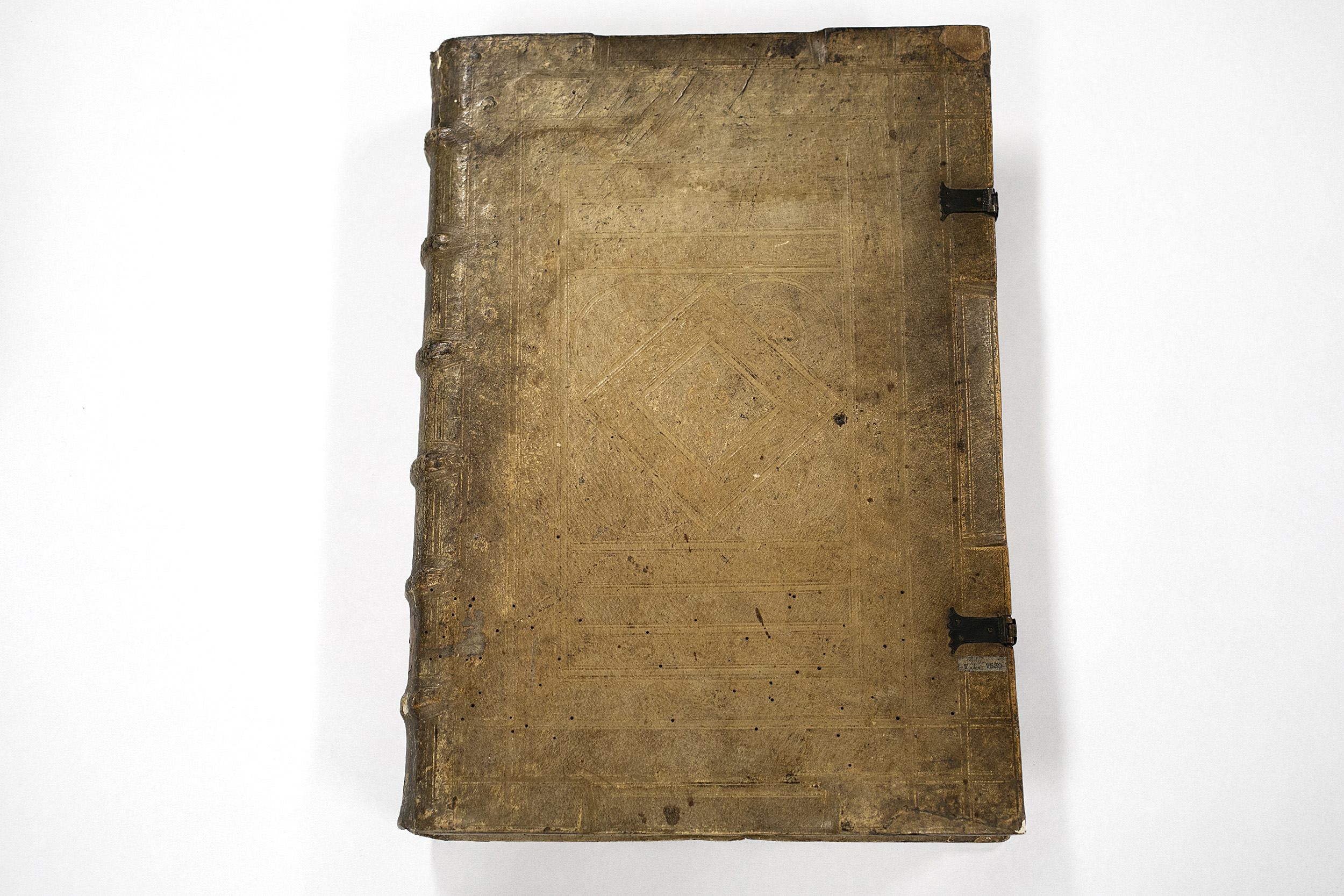

The “Eliot Indian Bible” was the first bible printed in America, in 1663. It was translated into the Algonquian language by the Massachusetts missionary John Eliot.

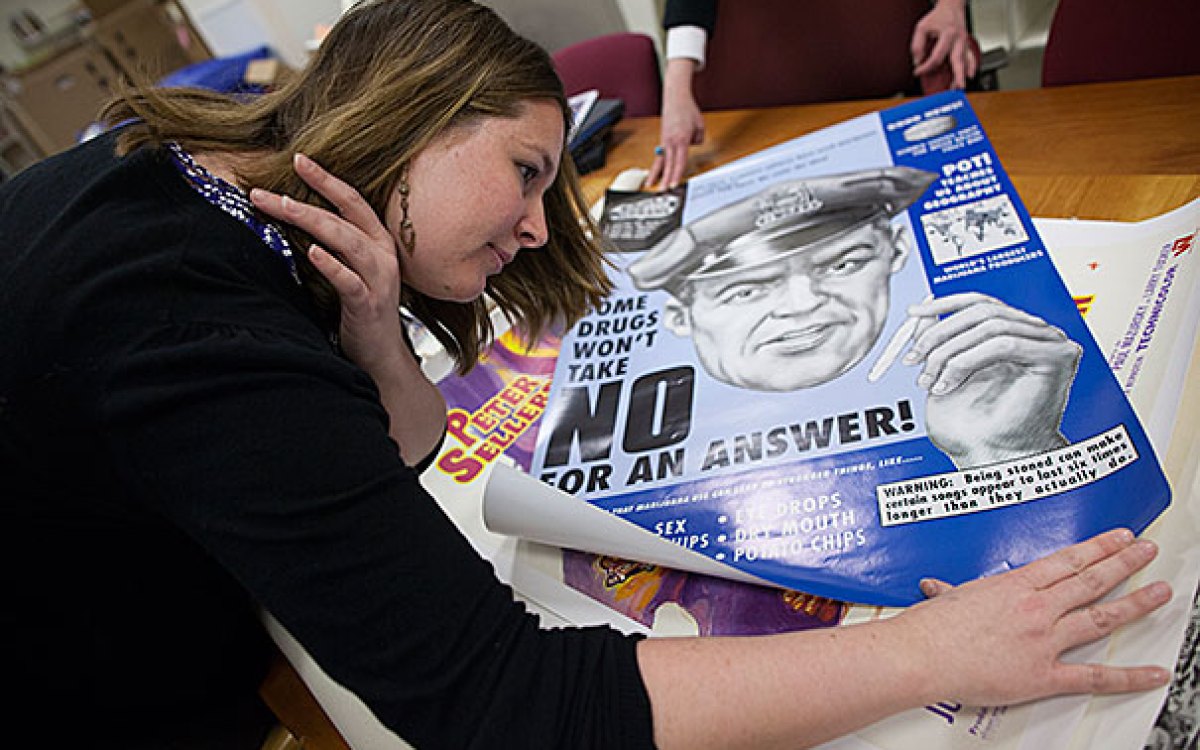

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The beauty of the book in all its forms

First-year seminar gets students to explore some of Houghton Library’s rarest volumes

For the first-year seminar “Harvard’s Greatest Hits,” David Stern wanted his small group of 21st-century hyperconnected undergraduates to put down their tablets, smartphones, and laptops and to pick up a book.

The idea was simple: Get about a dozen first-year students in a room and have them study some of the rarest and oldest volumes at Houghton Library, Harvard’s vast repository of art, culture, history, and more. “I don’t think they ever imagined how spectacular and rich the physical book could be, and how it really changed their ideas of what a book was or is,” said Stern, Harvard’s Harry Starr Professor of Classical and Modern Jewish and Hebrew Literature and a professor of comparative literature.

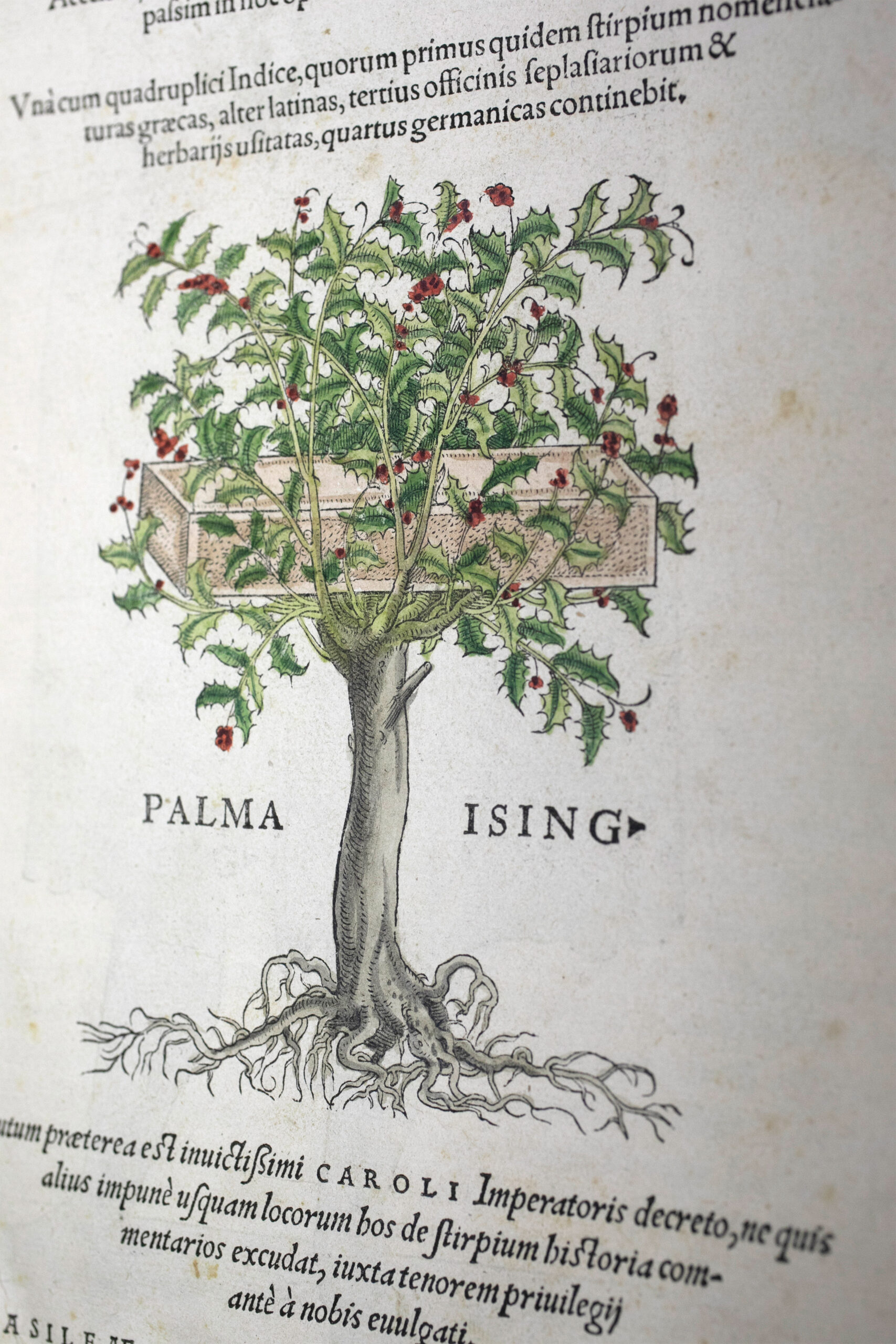

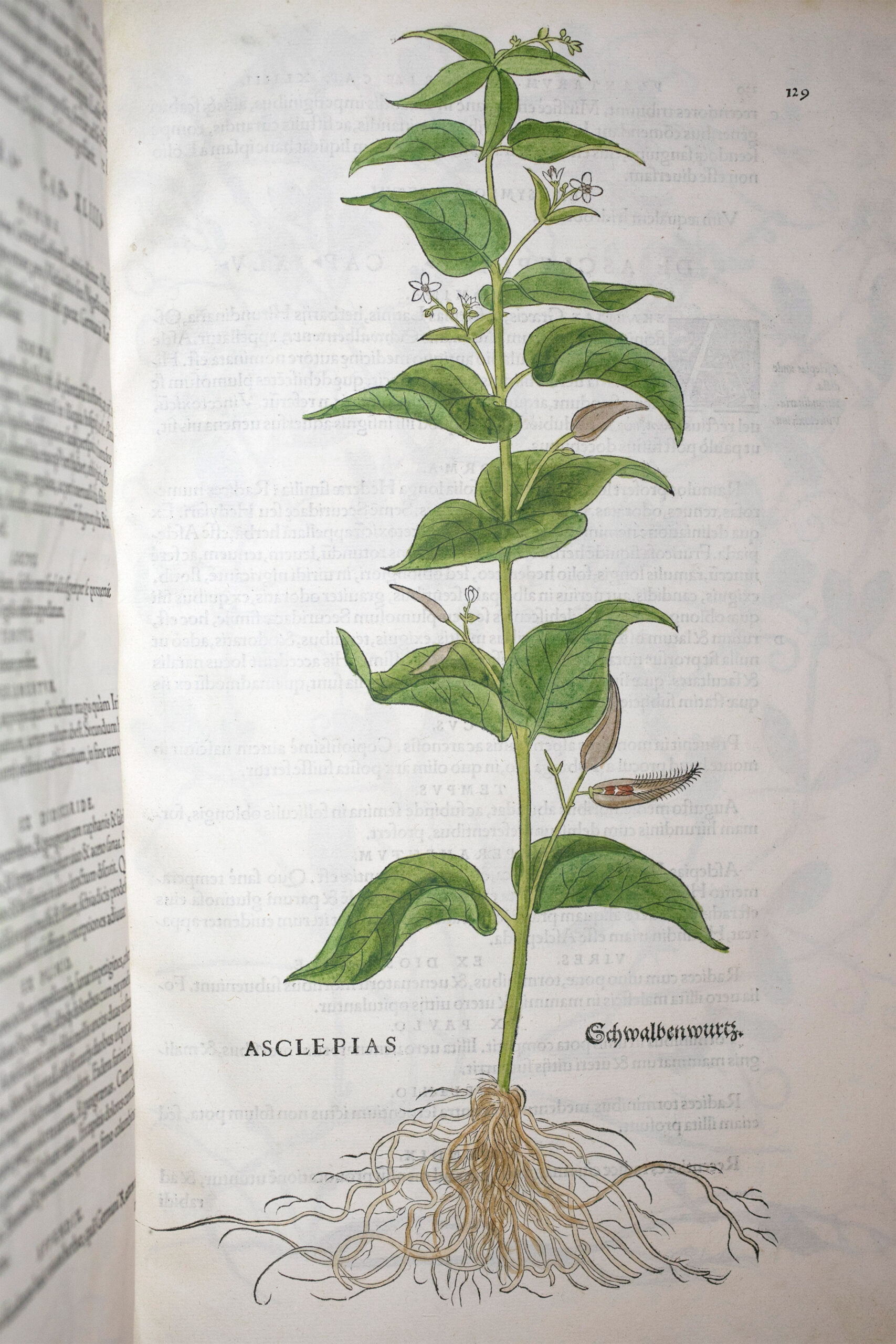

Stern, who studies books as material objects, said too often students think “all a book does is convey a text.” But he insists a book’s physical form can impart a range of critical information. The way the words are displayed on the page, the illustrations, even the size of a particular volume, Stern said, can affect a book’s meaning or how it’s interpreted.

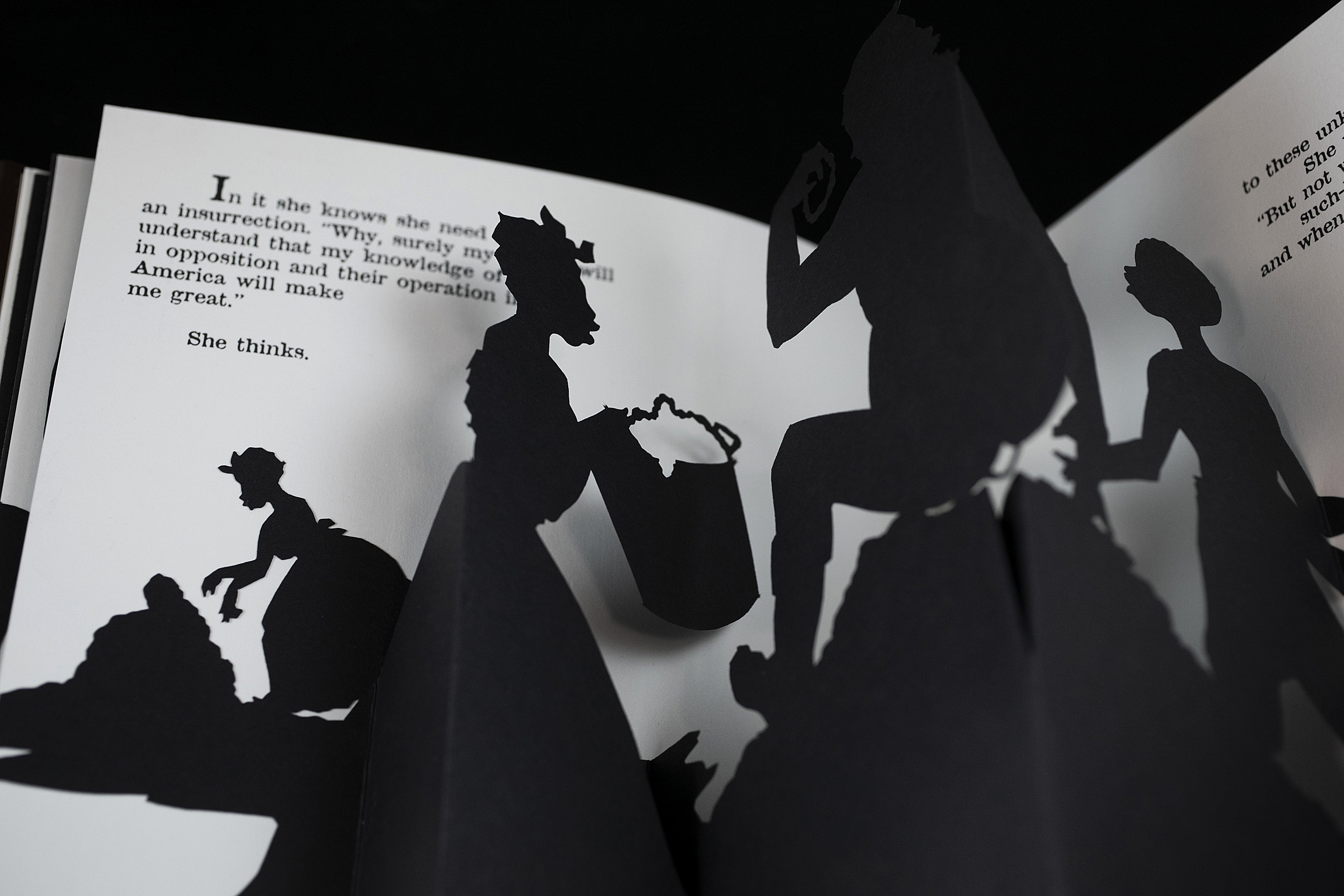

A page from the pop-up book “Freedom: A Fable” by the American contemporary artist Kara Walker. David Stern said his freshman seminar covered a wide range of materials at Houghton, including artist’s and children’s books, in an effort to help his students “change their idea of what a book was.”

During the fall semester, students met separately in small groups to explore a specific work, and then reconvened as a class at the library to discuss what they’d observed with help from Stern, visiting scholars, and library staff.

There were tactile highlights: They turned the pages of one of the volumes of Harvard’s Gutenberg Bible and created text on Houghton’s handpress. There were lectures on art: They studied the lush illuminated manuscripts and explored how illustrations in books throughout time have helped or hindered the meaning of their accompanying texts. There were history lessons: They looked at books as agents of change, such as the Luther Bible, and considered how they helped spread ideas around the globe. And there was the Bard: They investigated the types of textual changes that could be introduced into William Shakespeare’s work by printers, proofers, typesetters, and publishers by studying the source — Houghton’s 1623 First Folio.

Sometimes they found magic in the marginalia. In Herman Melville’s personal copy of Shakespeare’s works, next to a line of King Lear, the master storyteller scrawled “terrific” followed by an exclamation point. “This is the hand that wrote ‘Moby-Dick,’” said Stern with a laugh.

For their final project students wrote a paper on a book of their choice. Below is a sample of their selections, along with images of some of the other volumes they studied throughout the semester.

‘Heroides’

During the seminar, we looked at a variety of books from across history. One period of time I found particularly fascinating was the intersection between the late Renaissance and early print. Therefore, I decided to do my final paper on a Renaissance Latin manuscript of Ovid’s “Heroides” made in Italy around 1500. What drew me to this book was the clear, elegant humanist script and the vibrant illuminations. In the process of working on my paper I learned several things about the context behind the book in much greater detail — for starters, that the humanist movement ensured the survival of many classical texts by rescuing them from decrepit monasteries and copying them for posterity. In other words, some texts survived from only one manuscript and were nearly lost forever. Second, that the “Heroides” can be seen as consisting of two separate works in one volume, since Ovid composed these two sections years apart from one another. Finally, that this book has a very interesting history. It was made by an Italian illuminator working for a Spanish duke in Naples, and eventually wound up in the book collection of Sir Thomas Phillips (1792–1872), who arguably amassed the largest collection of books ever owned by a single person, having over 100,000. His estate, which took decades to sell everything, sold it to London booksellers who then sold the book to Harvard in the 1940s.

— Joseph Kester

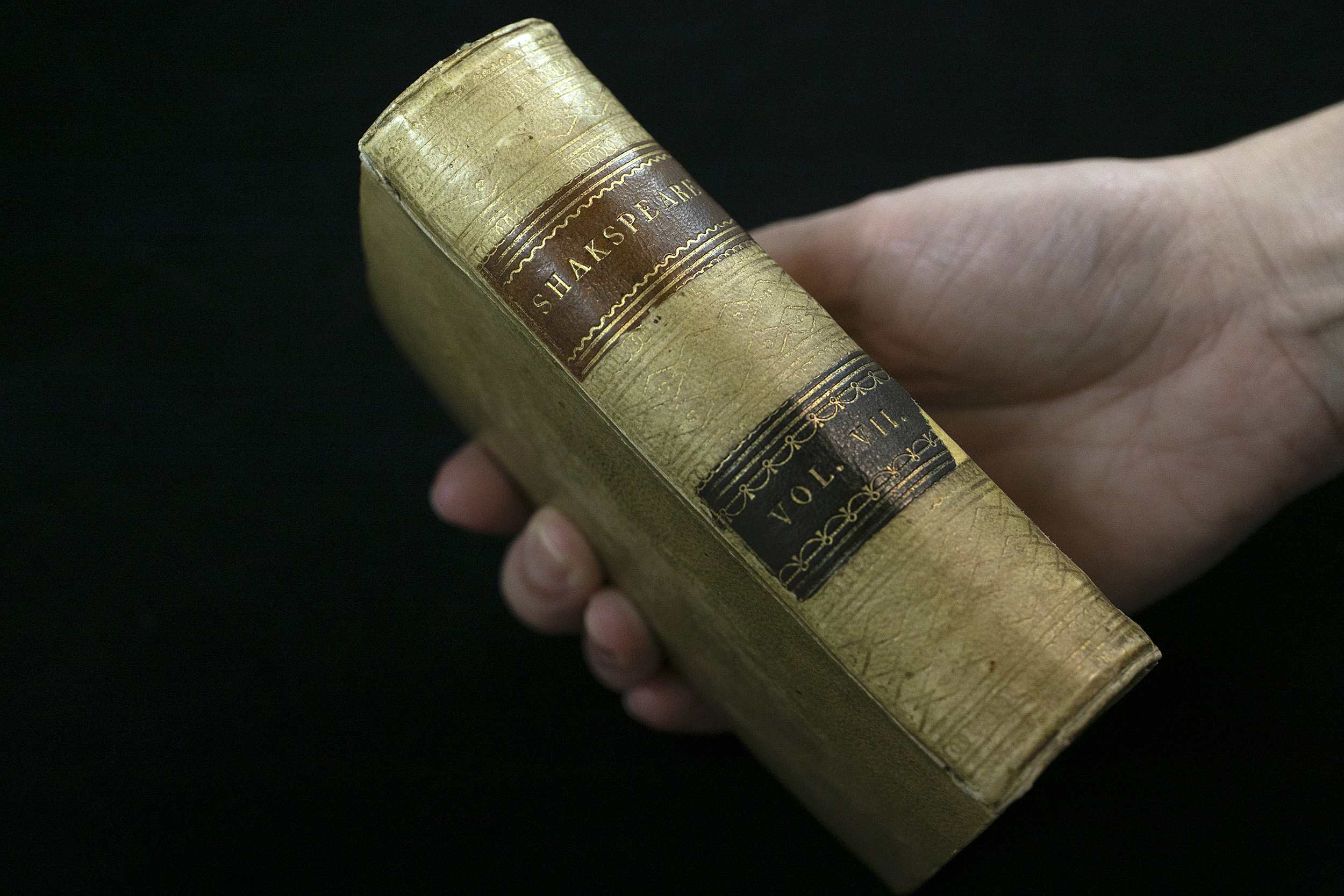

‘The Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare’

I based my project around the last book of an edition of Shakespeare’s complete works in seven volumes, previously owned by John Keats. I chose this book because I love Keats’ poetry, and Shakespeare, and was interested in what Keats’ copy of Shakespeare would look like and what lines in the text he chose to underline. This edition was the equivalent of a paperback in Keats’s time, so either he cared more about the words and less about his books’ appearance, or he did not want to spend as much money. The current binding would show how much Keats actually spent on it, as during the 1700s the binding would usually have been commissioned by the owner; but because the book was rebound after Keats’s death, it doesn’t. The book contains “Pericles,” “King Lear,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “Hamlet,” and “Othello.” The only plays he underlined are “Hamlet” (of which he underlined much of the play) and a few lines in “Pericles.” The peculiar degree to which the pages of “Romeo and Juliet” are worn, however, suggests that he did not pass over it and the other plays in the volume or read them in a different copy of the text — just that he chose not to underline them for some reason.

— Laura Coe

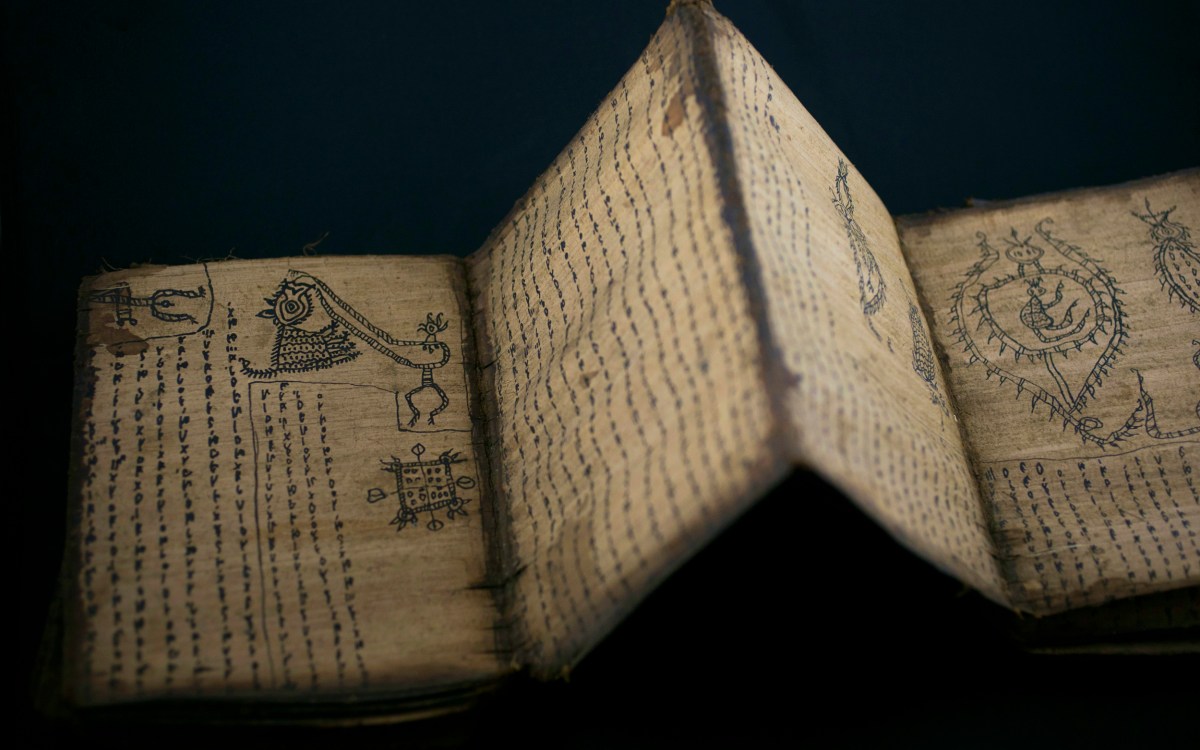

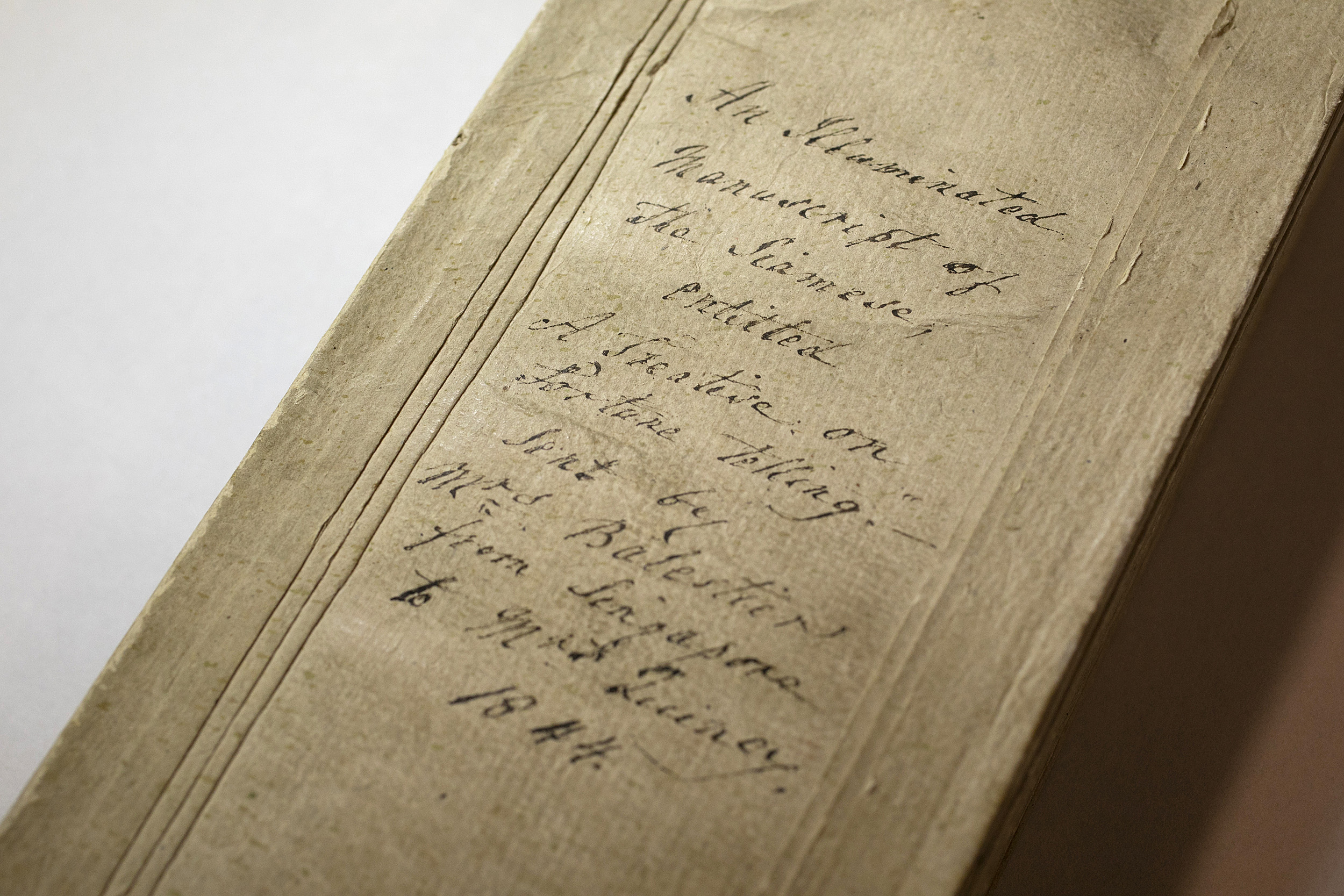

‘A Treatise on Fortune Telling’

For my final project I wrote about Houghton’s “A Treatise on Fortune Telling.” This manuscript comes from Thailand, is presumed to have been created before 1844, and was owned by the daughter of Paul Revere, Maria Revere. The manuscript folds like an accordion or like a brochure. The purpose of the text is to be used by a fortune teller (referred to in Thailand as a Mor Doo) to advise clients on love matches and life choices, and to provide personal analyses. Its pages feature illustrations of signs in the Thai zodiac alongside descriptions and indicators of traits. In between the sign-feature pages are compatibility pages, designed to assist the Mor Doo in their analyses. I found the manuscript captivating from the moment I heard about it. In fact, I was willing to write my final 10-page paper about the manuscript before I found out that there was a translation from Thai to English. The illustrations are vibrant and the gaps between the translation and illustration hint at a greater knowledge possessed by Mor Doos within Thailand, and builds a bridge toward understanding the importance of fortune telling in Thailand.

— Matilda Scheftel

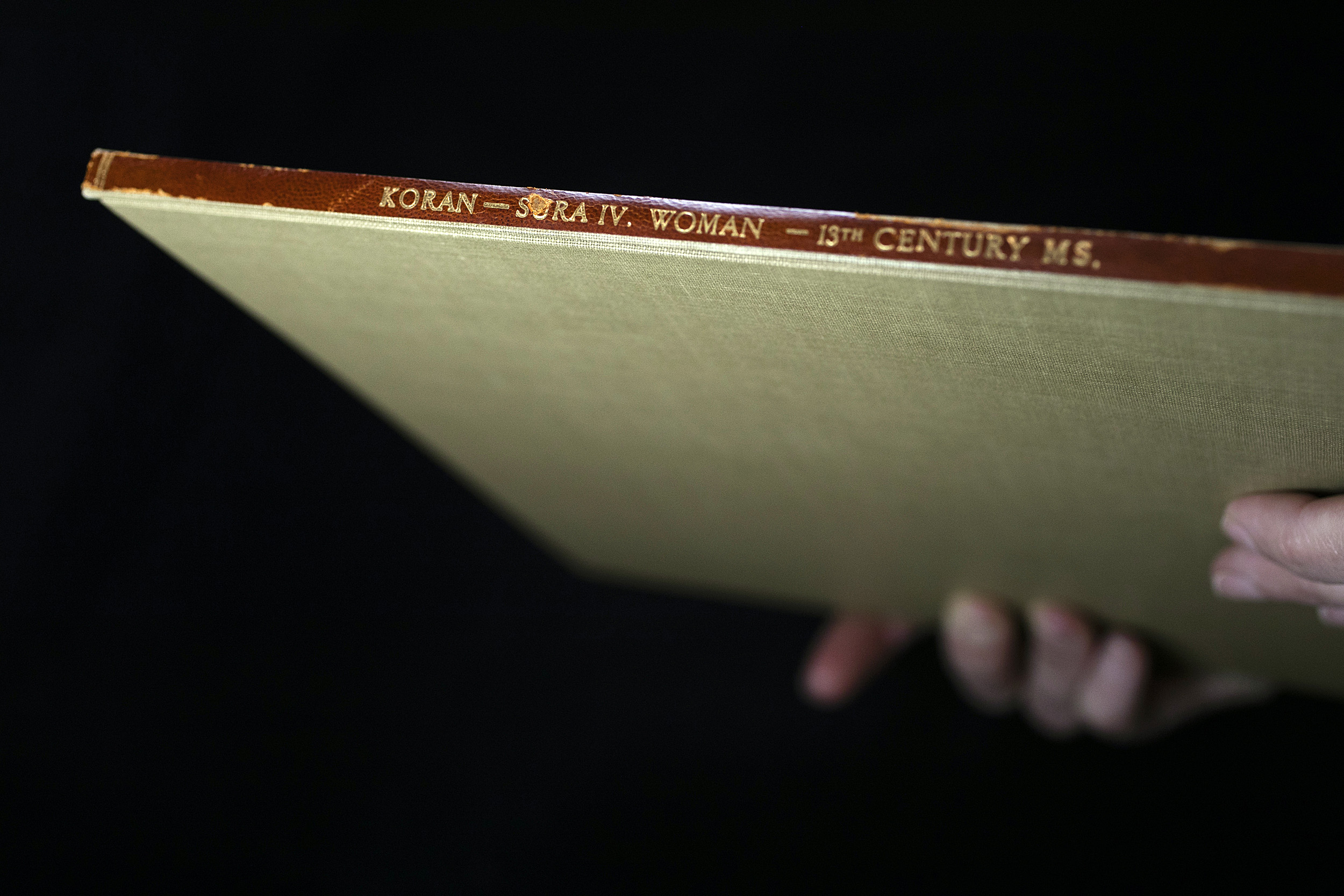

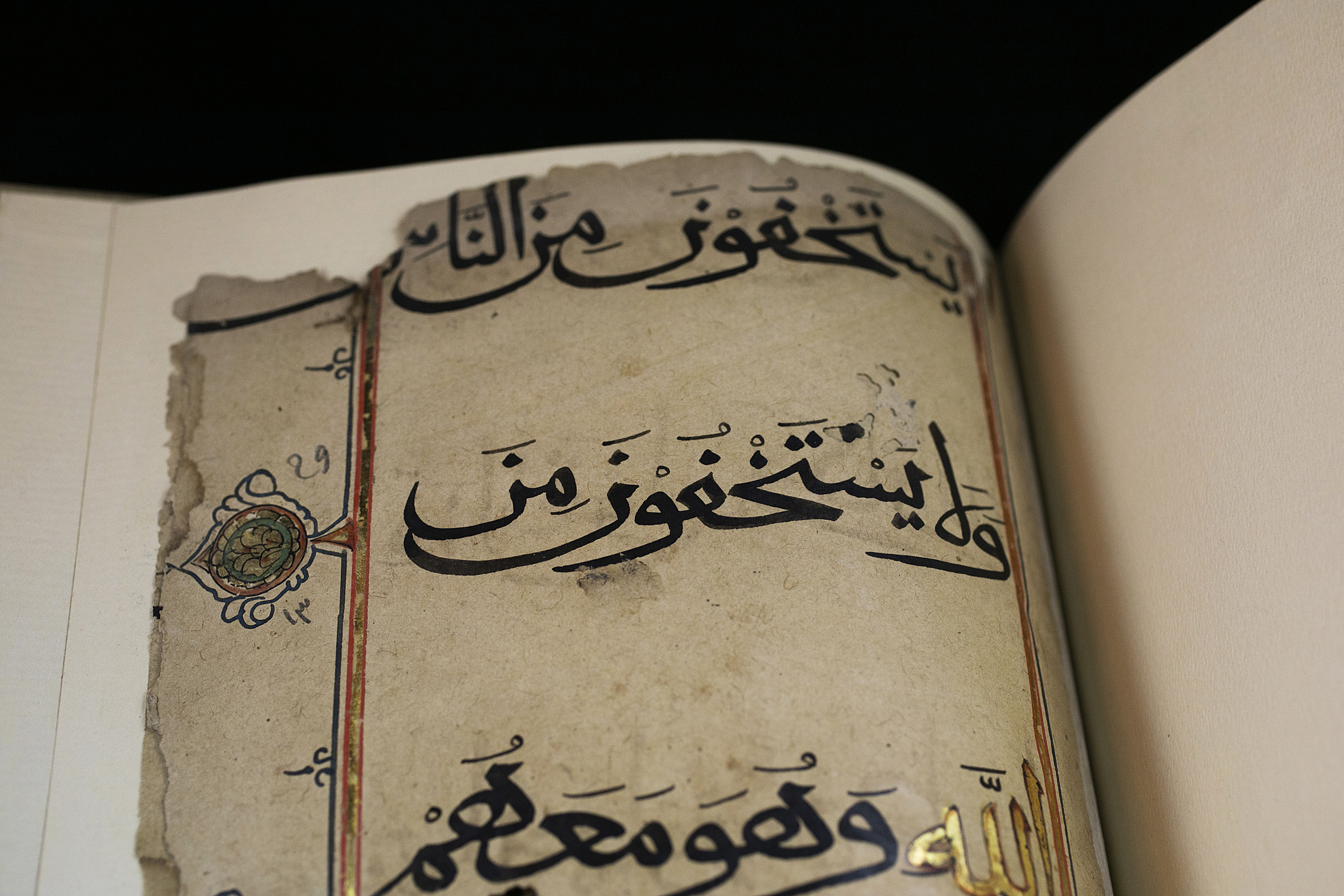

A 13th-century Koran

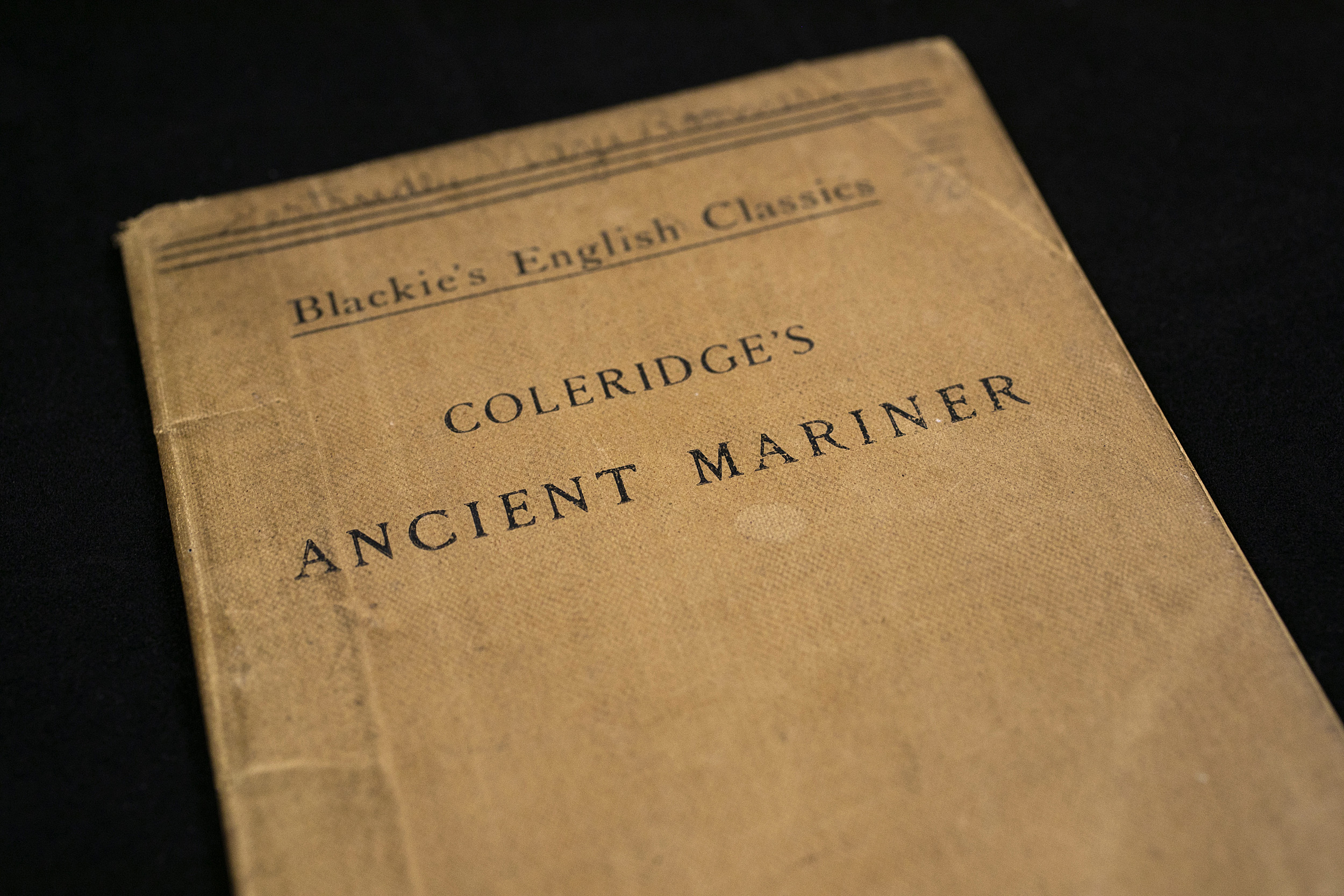

‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’

I chose to write my final paper on a copy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” owned and annotated by Elizabeth Bishop, the prolific 20th-century poet. The book is a thin pamphlet [containing] the famous Romantic piece, published by Blackie and Sons as part of an English Classics collection at an unknown date in the 20th century. It came to Houghton from Bishop’s private library. She took notes throughout, marking literary devices like alliteration, personification, and “beautiful similes” in the margins, as well as underlining certain passages. I was thrilled by the opportunity to study this book — I love Bishop, but beyond that, I think there’s something intimate about someone’s annotations. By reading Bishop’s copy, we read it alongside her, creating a unique shared experience. The book puts us in direct conversation with both Bishop and Coleridge. Additionally, Bishop’s reading notes show her metric for evaluating poetry, illuminating her relationship with her own work.

— Ezra Lebovitz

‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica’

For my final paper, I chose to research anatomist Andreas Vesalius’ landmark anatomical text, the “De humani corporis fabrica.” The book not only represented a revolution in the study of anatomy, but also in the usage and aesthetics of the codex form. When we first studied the anatomical text in class, I was immediately stunned by the beautiful, cerebral renderings of the human body. Whereas most modern textbooks I’ve seen presented the body as static and flat, Vesalius rendered the bodies as dynamic and vivid, posed against lush backgrounds of forests and rivers. After spending enough time with the “Fabrica,” you’ll realize that Vesalius strove much more than to just accurately portray the body — he strove to capture the aesthetic and biological beauty hidden away in every human body. From the book’s robust binding to its intricate woodblock illustrations to its complex, multipage layout, the book is truly a manifestation of this striving. It was a humbling experience to study this book.

— Albert Zhang

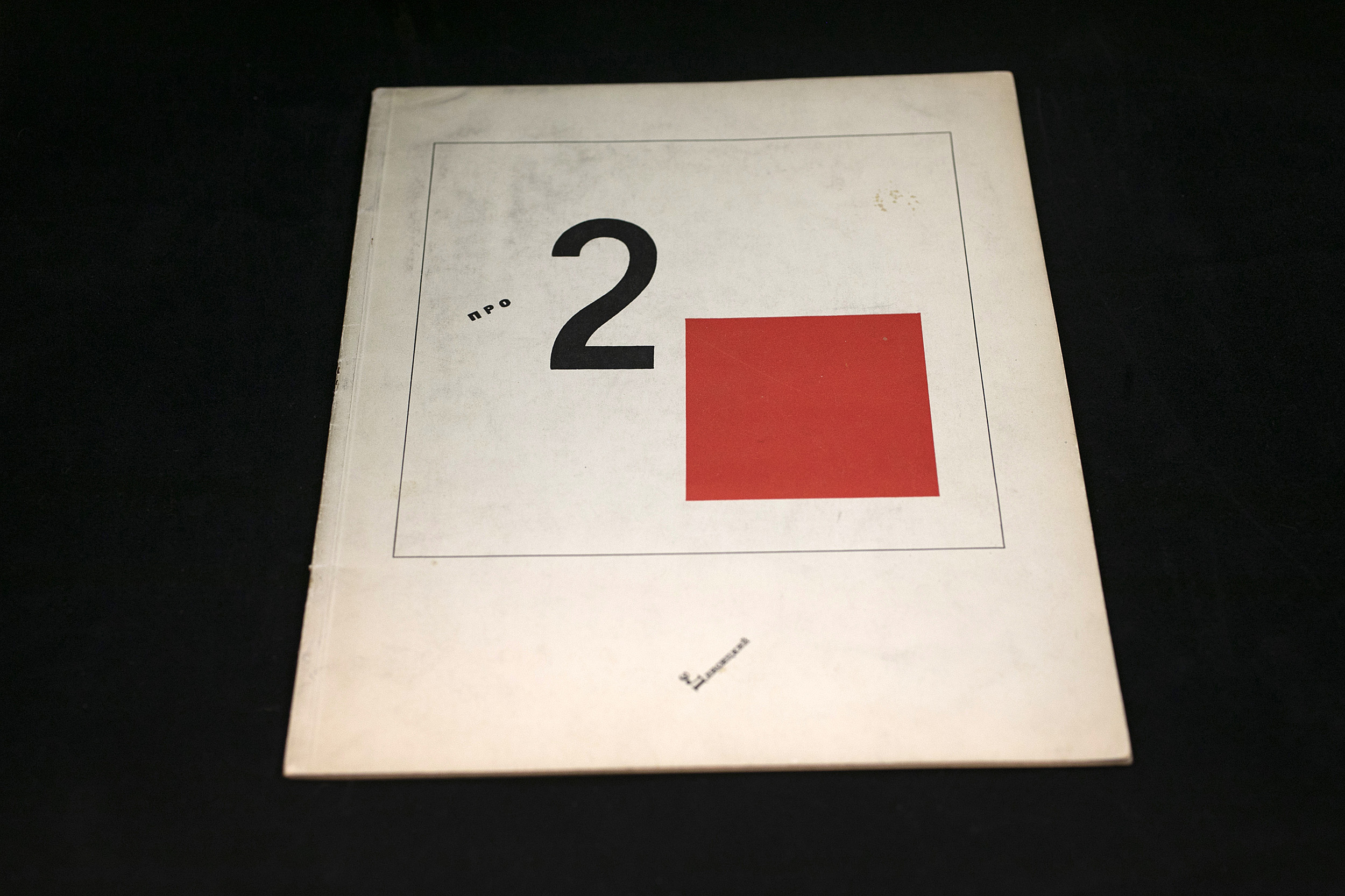

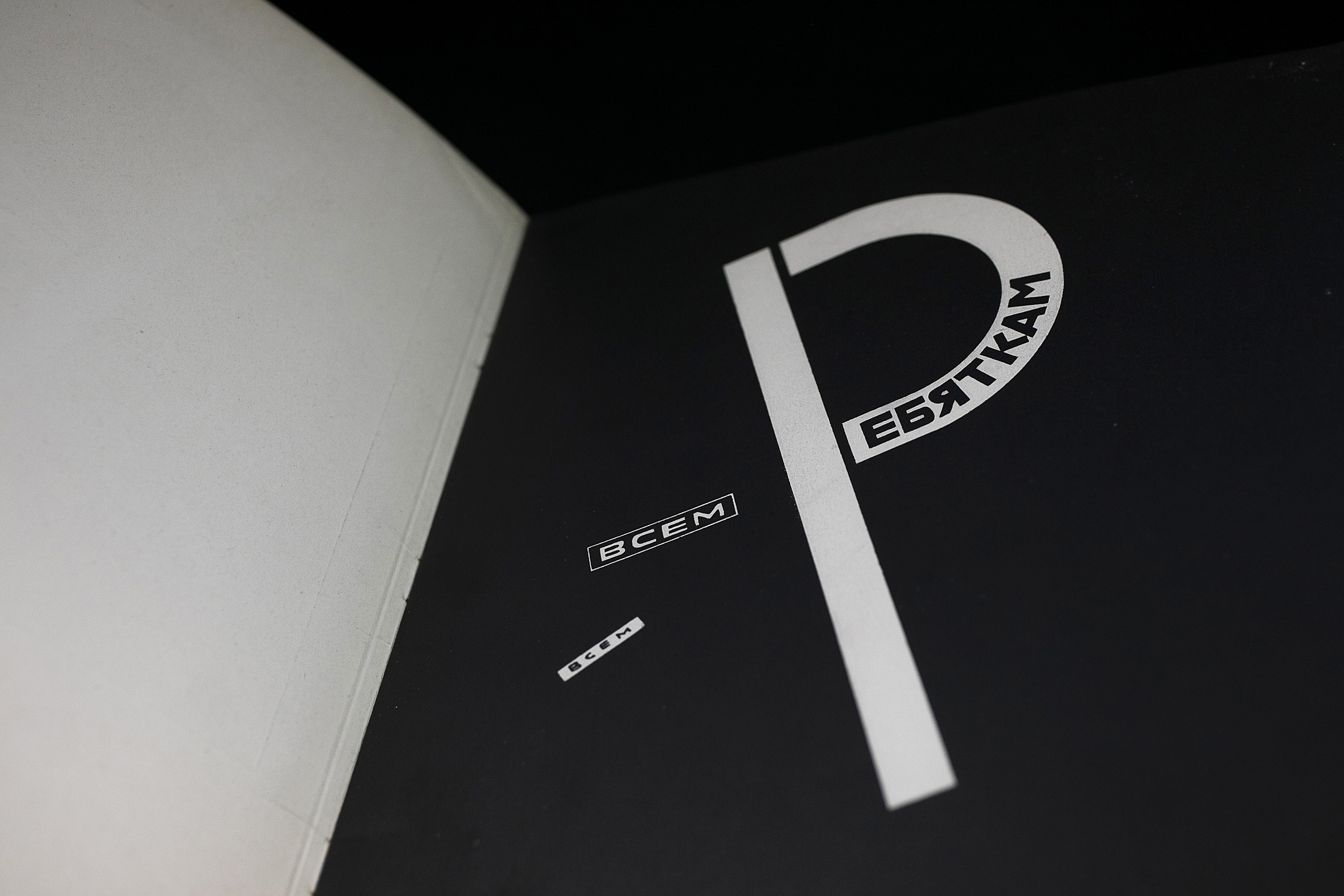

‘About Two Squares’

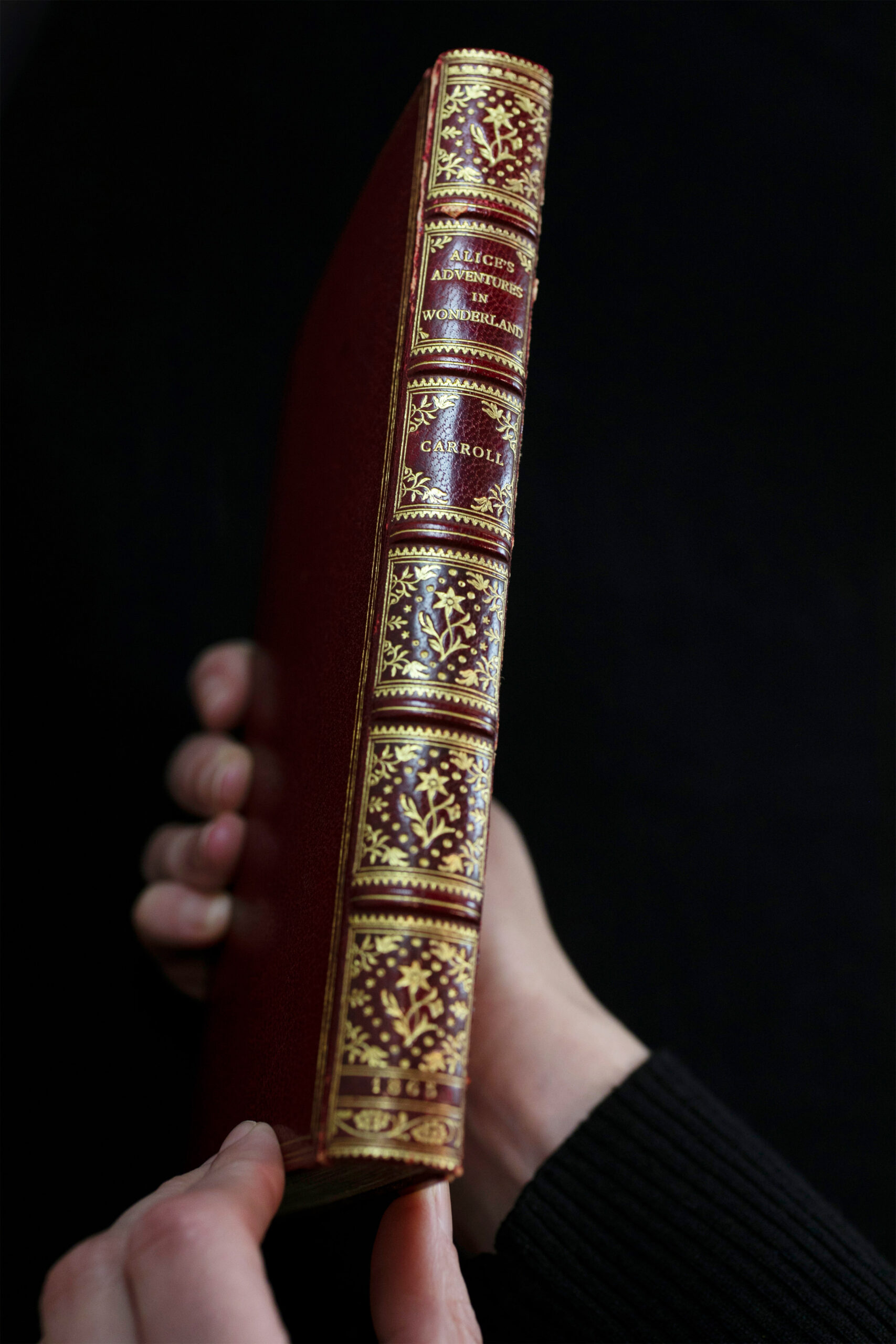

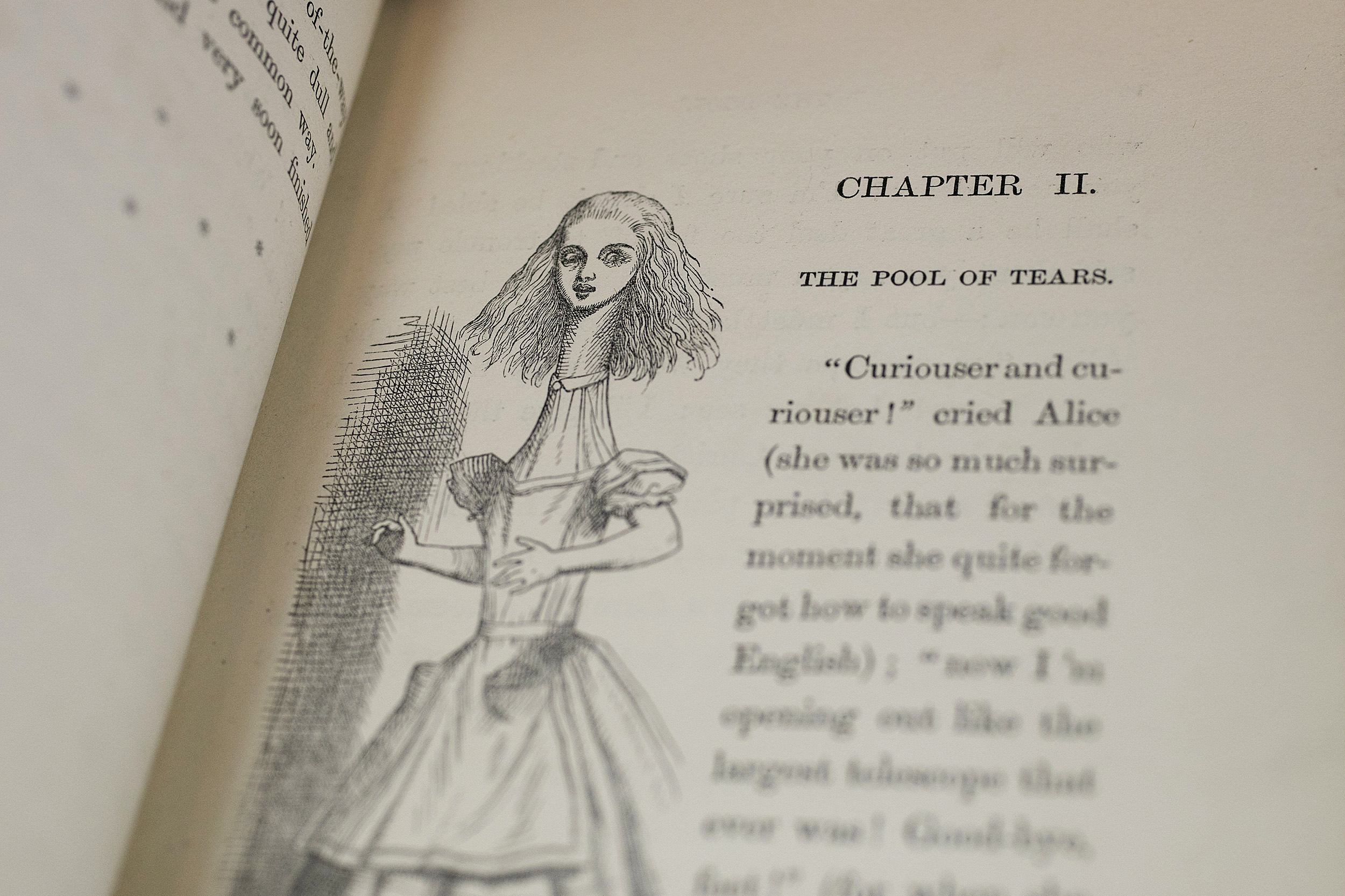

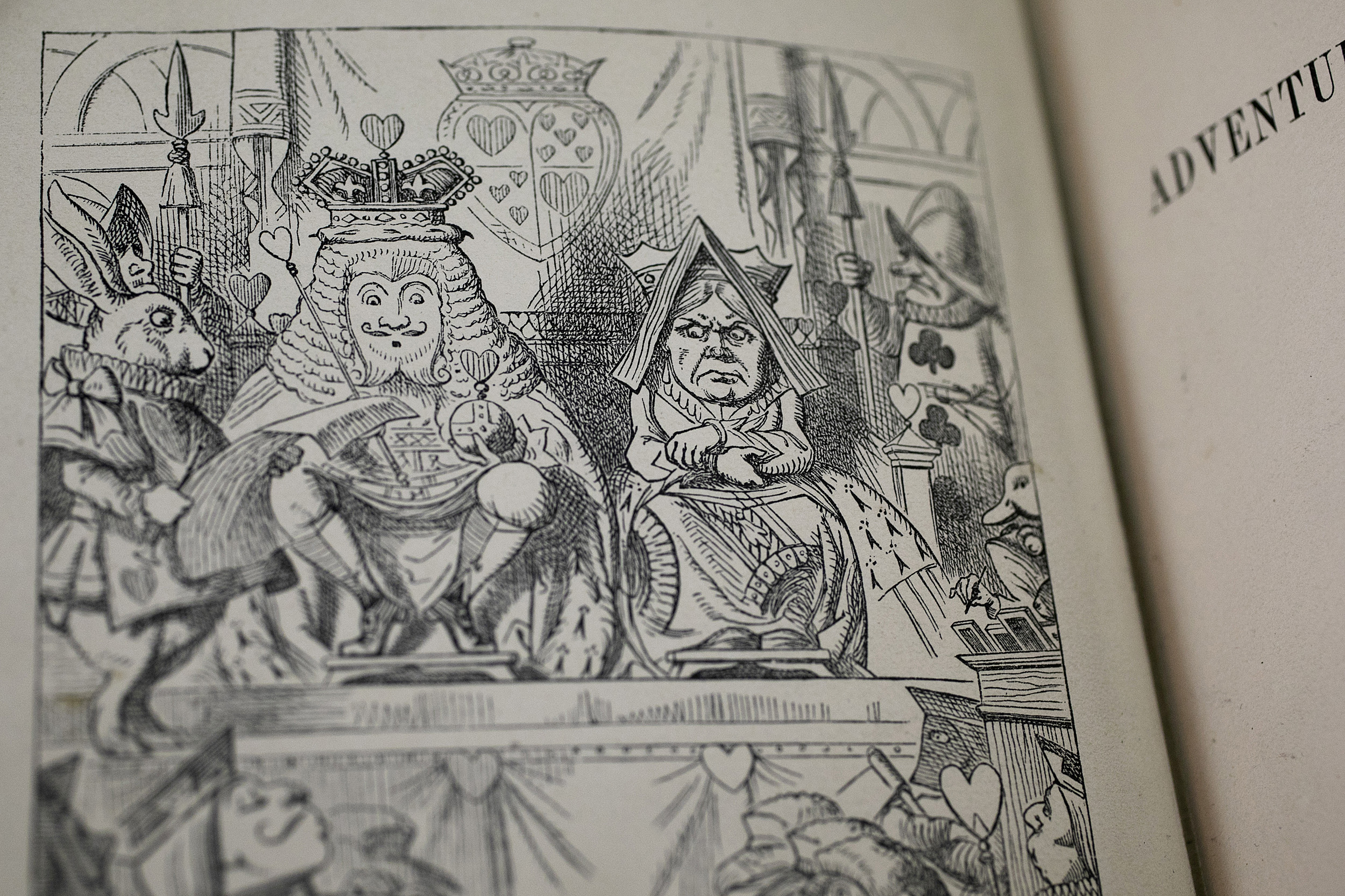

‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’

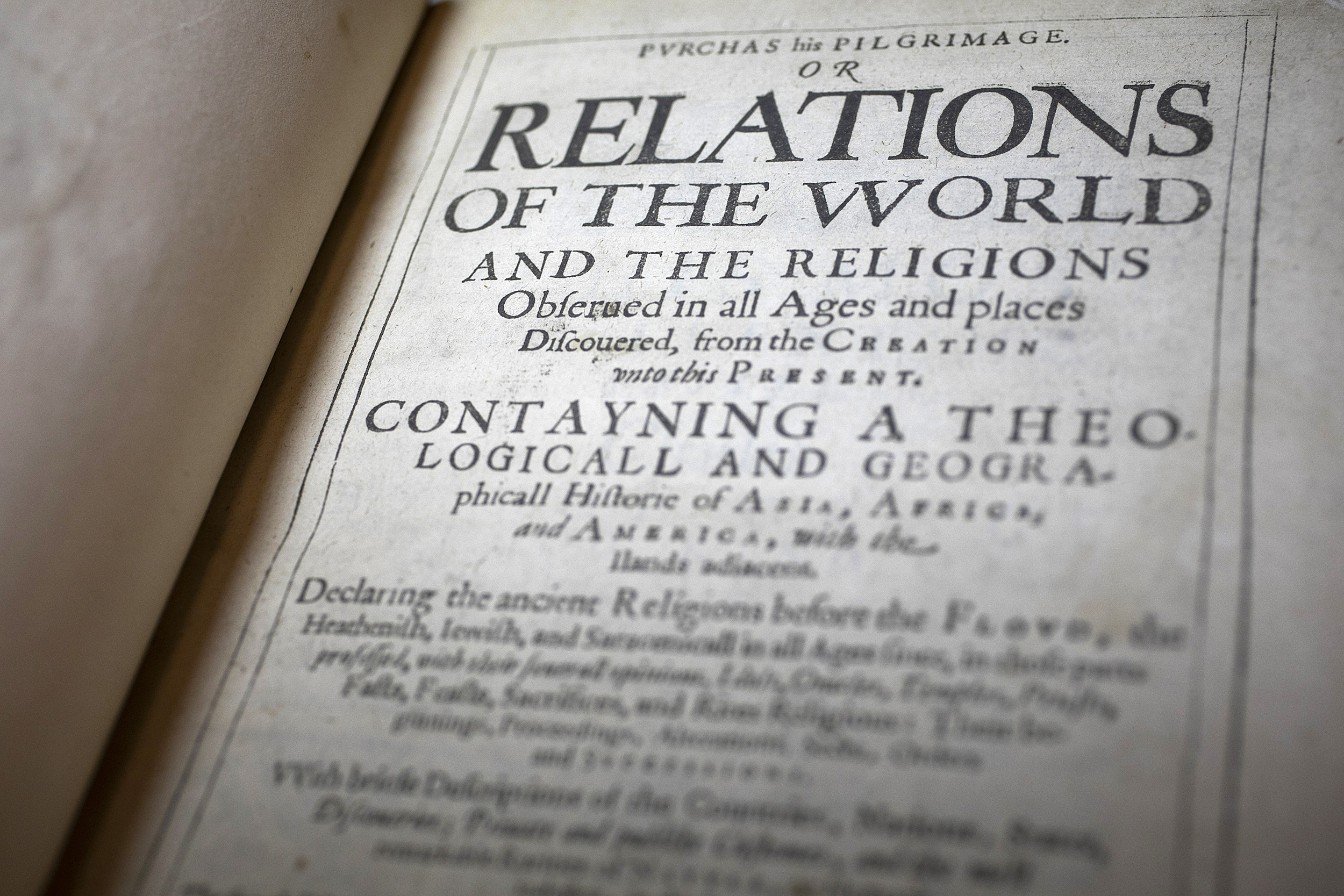

‘Purchas His Pilgrimage’

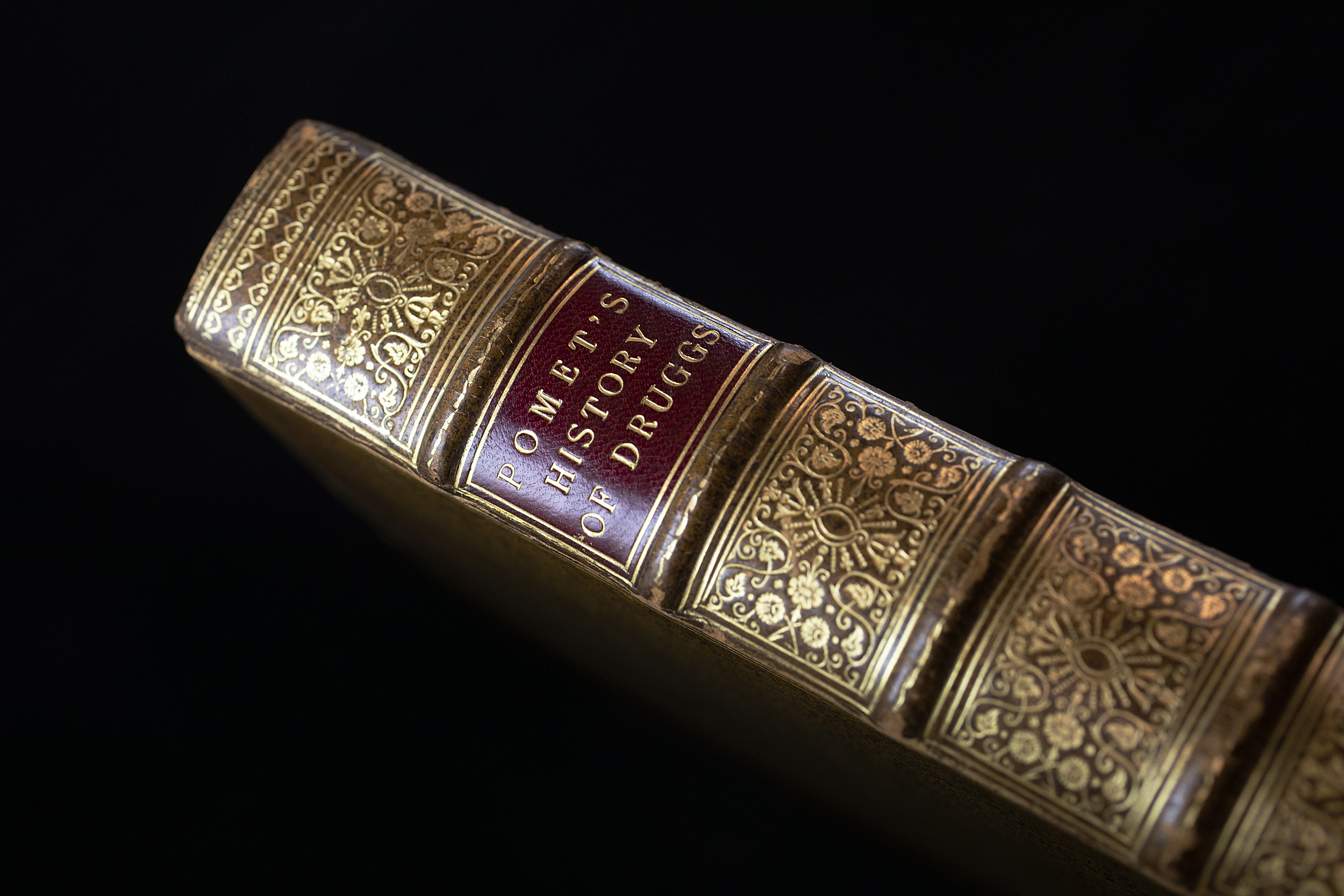

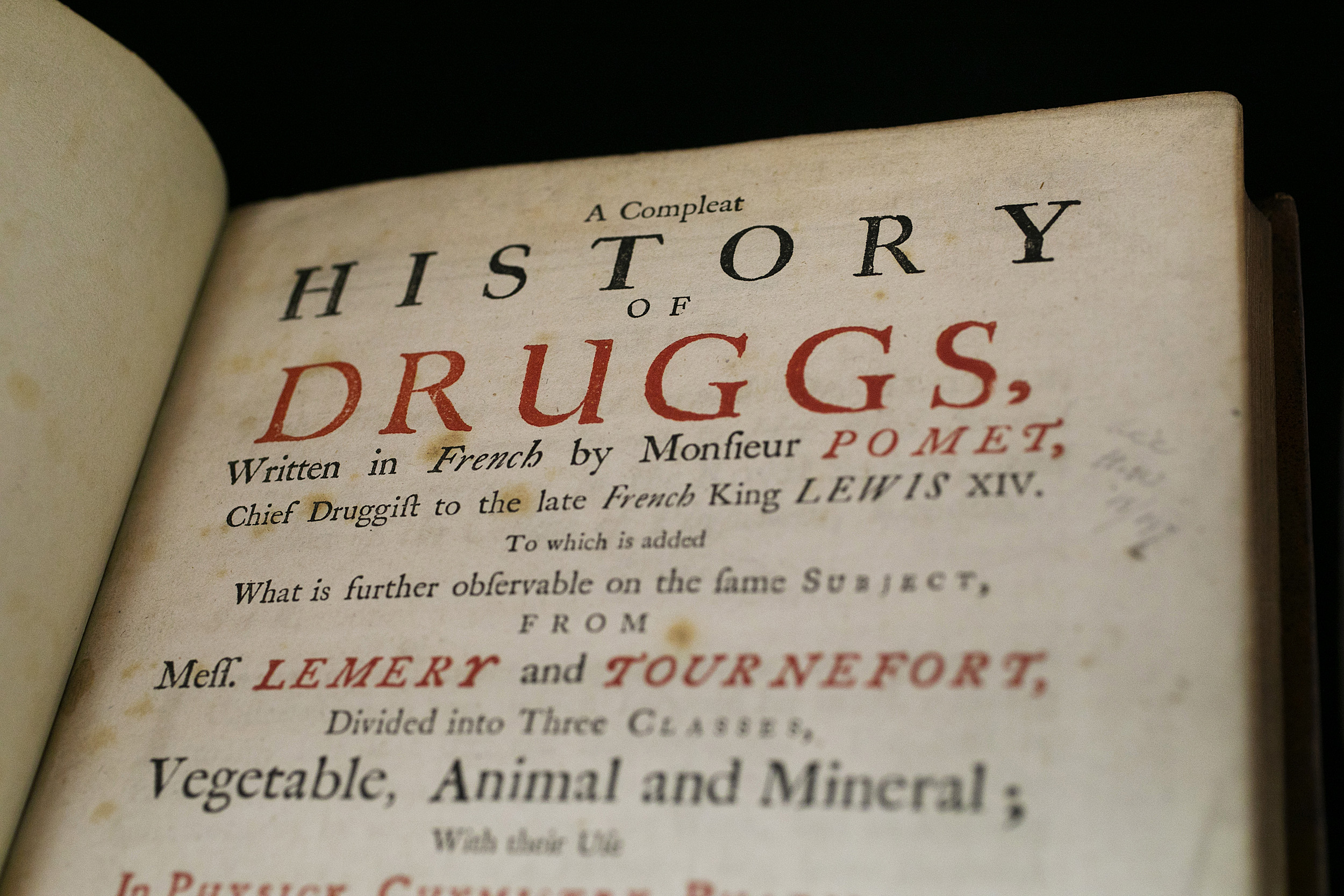

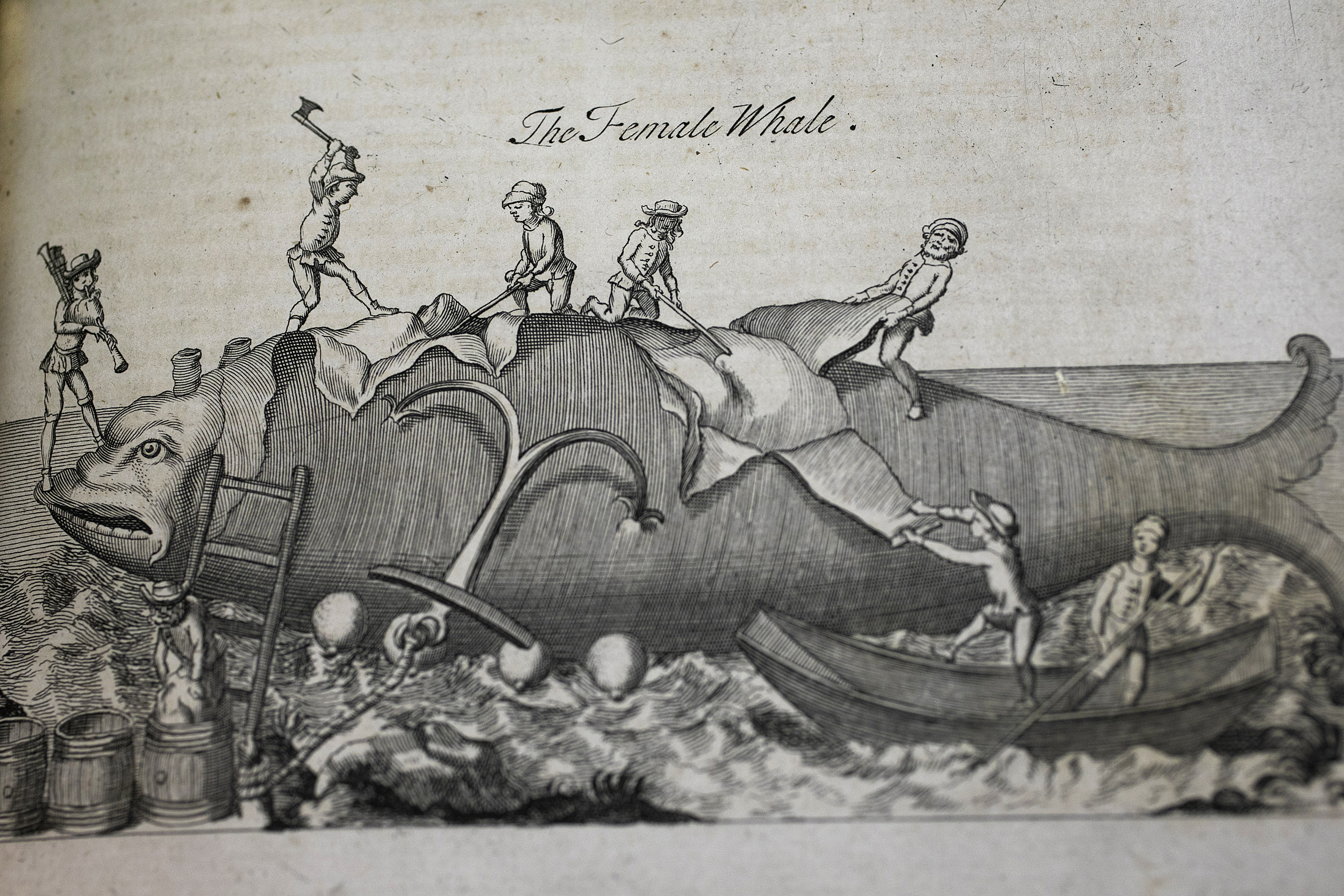

‘A Compleat History of Druggs’

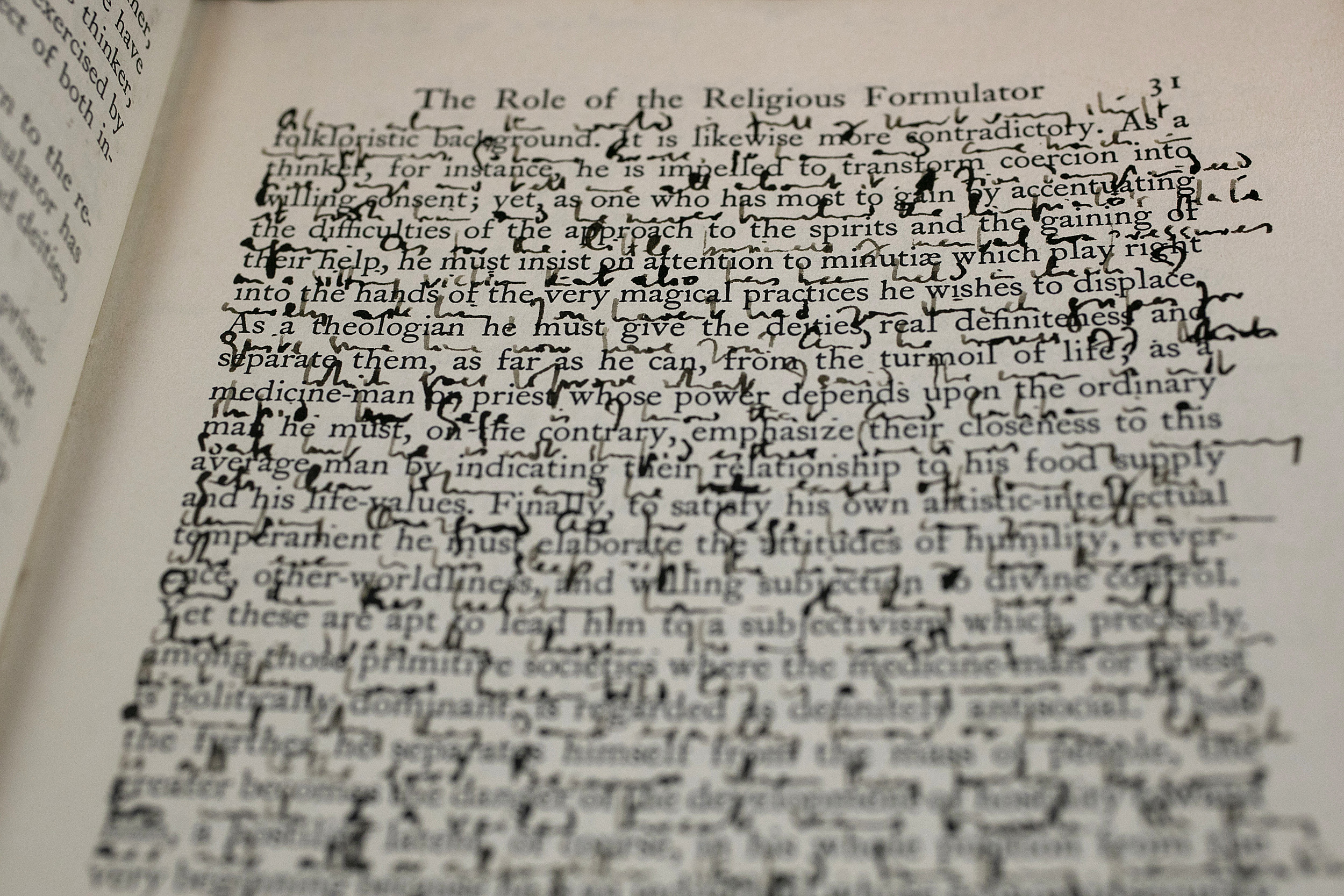

Prison writings of Wole Soyinka

Houghton’s collection includes a trove of papers from the Nigerian playwright, poet, essayist, and 1986 Nobel Laureate for literature Wole Soyinka. The archive contains his prison diaries, lines written down between the typed texts of the books he read while he was imprisoned during the Nigerian Civil War in the 1960s. Here, the author captured his thoughts in the pages of “Primitive Religion: Its Nature and Origin” by the American cultural anthropologist Paul Radin.

compact-top

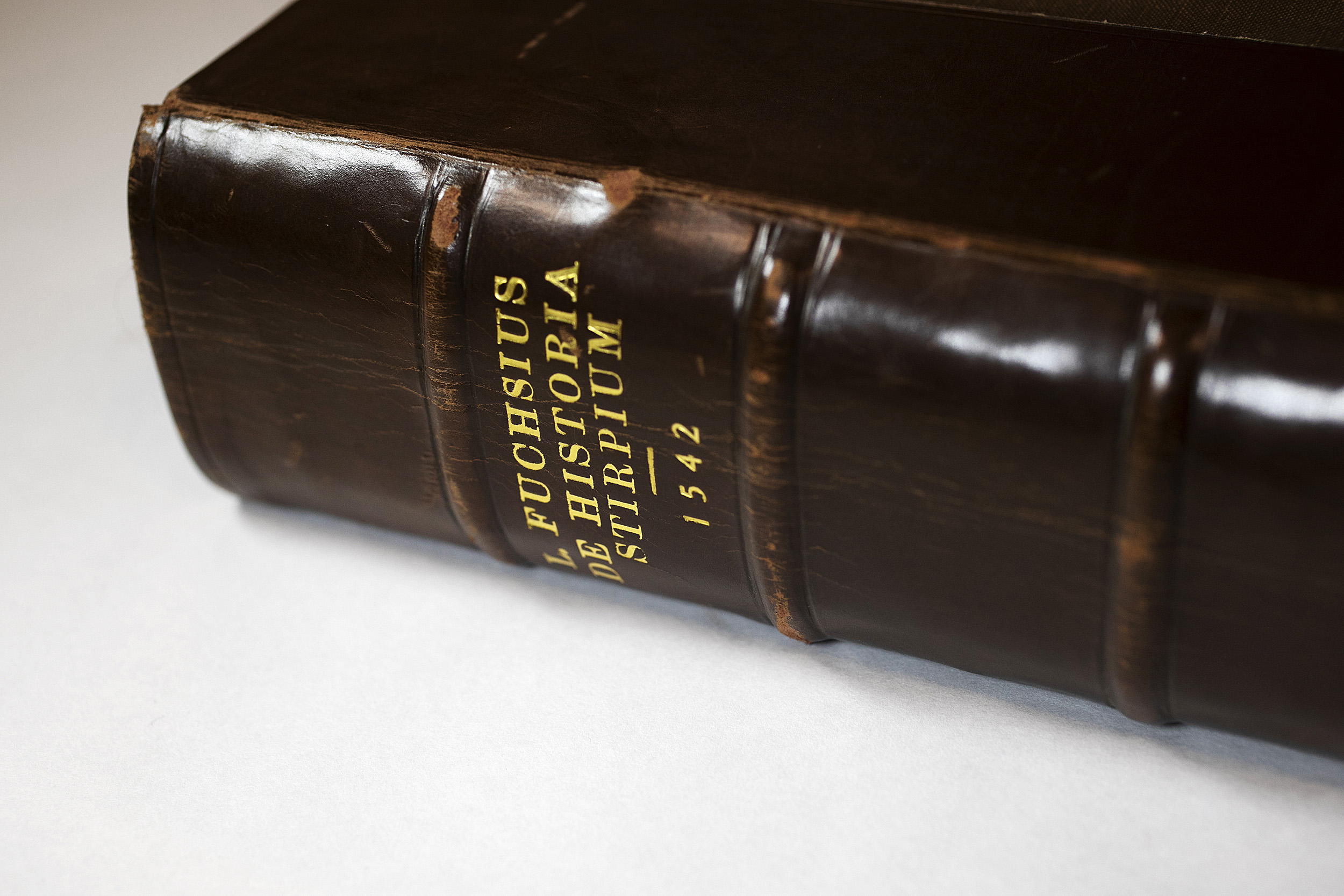

‘De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes’