The Bradley Estate with pond and geese, 1953.

Courtesy of the Eleanor Cabot Bradley Papers, The Trustees Archives & Research Center

Living legacies

Arnold Arboretum celebrates women who grew New England in the 20th century

As New England waits for spring — and observes Women’s History Month — the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University is celebrating the roots of the region’s traditions of landscape design and social outreach. “Cultivating Legacies: New England Women in Horticulture and Landscape Design” salutes six notable women from the turn of the last century with a seminar on Saturday from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. in the Arboretum’s Hunnewell Building.

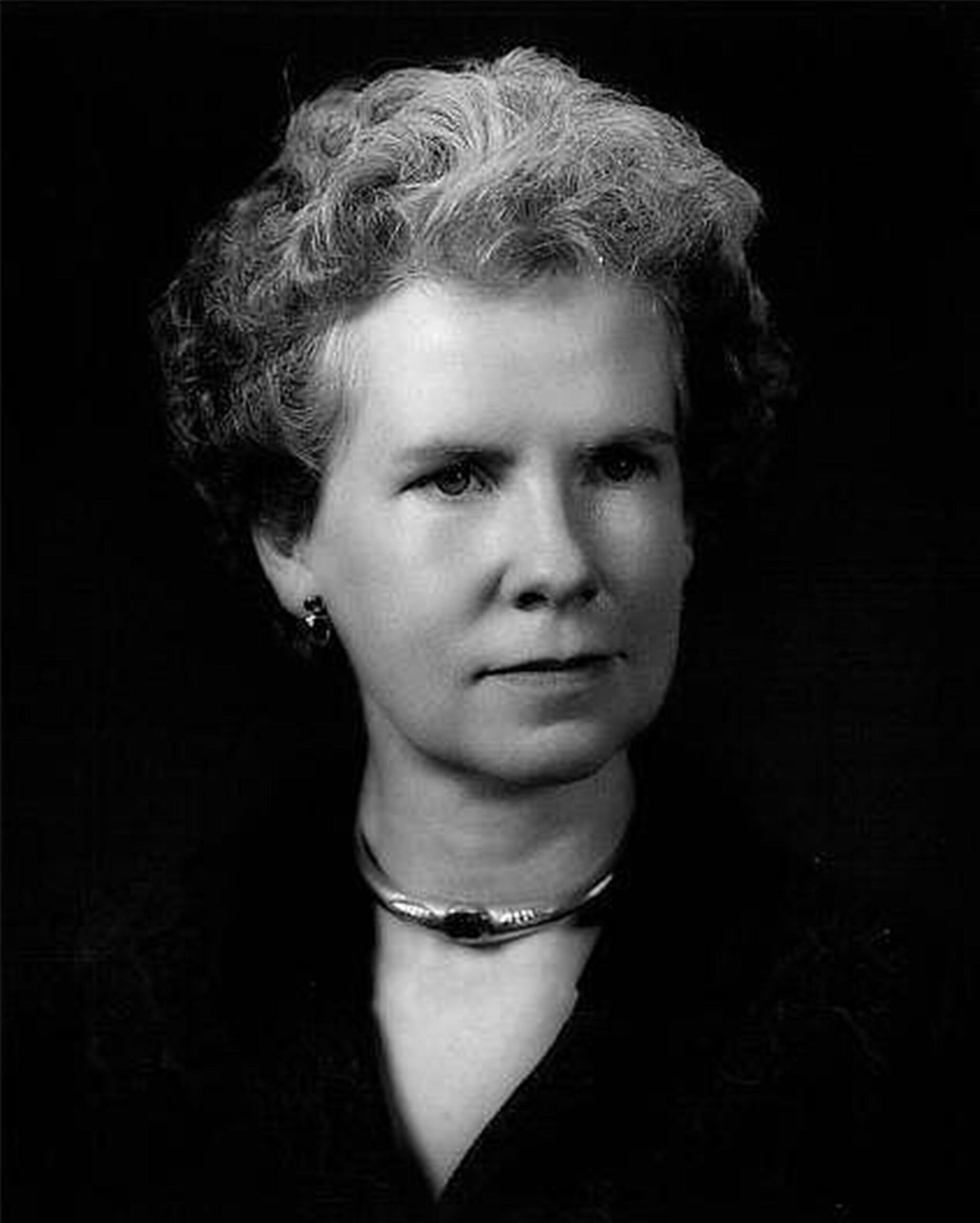

The women being honored — Mary “Polly” Wakefield, Marjorie Russell Sedgwick, Martha Brookes Hutcheson, Eleanor Cabot Bradley, Marian Roby Case, and Rose Standish Nichols — may not be household names, but each played what could be called a groundbreaking role in New England horticulture.

In addition to their ties to the Arboretum, all of these women shared a common goal, said Lisa Pearson, head of library and archives at the Arnold Arboretum Horticultural Library: “The improvement of plants but also the improvement of society” through landscape design and horticulture.

Wakefield (1914–2004) will forever be linked to the Kousa dogwood trees she bred on her family’s farm in Milton. But she was also an advocate for ecology and education. A member of the Massachusetts Governing Board of the Nature Conservancy and of the Highway Corridor Land Use Committee of the Massachusetts Department of Public Works, Wakefield pushed through the state legislature bills to protect nongame wildlife and set aside a variety of ecological habitats for endangered wild plants and animals. She also created the private Mary M.B. Wakefield Charitable Trust to ensure that the farm that had been in her family for 300 years would be used for education and community engagement after her death. Today, more than 2,000 schoolchildren, from kindergarten through fifth grade, attend these programs, which are open to any interested school program. “She realized it was important for children to have hands-on opportunities,” said Debbie Merriam, the trust’s landscape director.

Mary Wakefield and Martha Brookes Hutcheson were among six notable women who contributed to New England’s horticulture.

Mary M.B. Wakefield Charitable Trust and Morris County Park Commission

Sedgwick (1896–1978) was a propagator of rare plants, and in collaboration with the Arboretum introduced new plants to Long Hill and Sedgwick Gardens, her home in Beverly. The gardens, which are open to the public, are flanked by 100 acres of woodland, an apple orchard, meadows, a children’s garden, and agricultural fields, including a 2-acre organic vegetable farm, which is run as a community-supported project.

Hutcheson (1871–1959), a landscape designer who studied at MIT, promoted conservation and what Merriam called “smart ecologies,” such as planting urban trees and propagating native plants. Perhaps more important, the author of 1923’s “The Spirit of the Garden” believed that gardens and public green spaces played important roles in the community. Through her writings and speaking engagements, she promoted “positive social and cultural change through landscape design,” said Merriam, noting that her vision crossed class lines. In Hutcheson’s view, “everyone had something to contribute,” Merriam said.

When Bradley (1893–1990) inherited her uncle’s 90-acre Canton estate in 1945, she preserved its turn-of-the-century surroundings, maintaining the family’s commitment to the elegant gardens, fields, and woodlands and added a greenhouse and studio. Bradley, who attended classes at Radcliffe College and workshops at the Arboretum, was a leader of Boston gardening associations and a member of the Arboretum Visiting Committee, a group that reported on Arboretum activities for the Harvard University Board of Overseers.

As the proprietor of Hillcrest Gardens, Case (1864–1944) ran what would now be called an educational enrichment program, Pearson said. Each summer, boys would work cultivating fruits and vegetables in the gardens while receiving instruction in botany and related sciences via weekly lectures. (Girls were invited to write essays to compete for the Hillcrest Prize.) Although Case particularly wanted to groom future farmers, Pearson said some of her attendees went on to Harvard. Notably for its time, the program was relatively open, with the son of Case’s African-American butler and the children of immigrants working and studying alongside those of Weston gentry. “She really wanted to … create good citizens for the future,” said Pearson.

Eleanor Cabot Bradley and Marjorie Sedgwick tending to their gardening.

Courtesy of the Bradley Family’s personal collection, the Long Hill Photo Collection, and the Trustees Archives & Research Center

Nichols (1872–1960) trained for her successful 40-year career in garden design at Harvard’s Bussey Institute, a now-defunct school of agriculture and horticulture. The designer and suffragist wrote three books about European gardens as well as articles on horticultural topics in magazines such as House & Garden, from between 1899 and 1954. She designed at least 70 gardens across the country. Her family home in Beacon Hill, which she owned from 1935 until her death in 1960, is now the Nichols House Museum.

Arboretum horticulturist Laura Mele says she is encouraged that after many years of invisibility, women in horticulture throughout history are being recognized. She feels she is working at the Arboretum in part because of what women have been doing since the profession began.

“These talented and knowledgeable women of history are like a buoy for me,” said Mele. “Knowing that they were contributing to and influencing horticulture so many years ago gives me a great sense of pride.”

The seminar is co-sponsored by the Trustees of Reservations, the Mary M.B. Wakefield Charitable Trust, and the Arnold Arboretum.