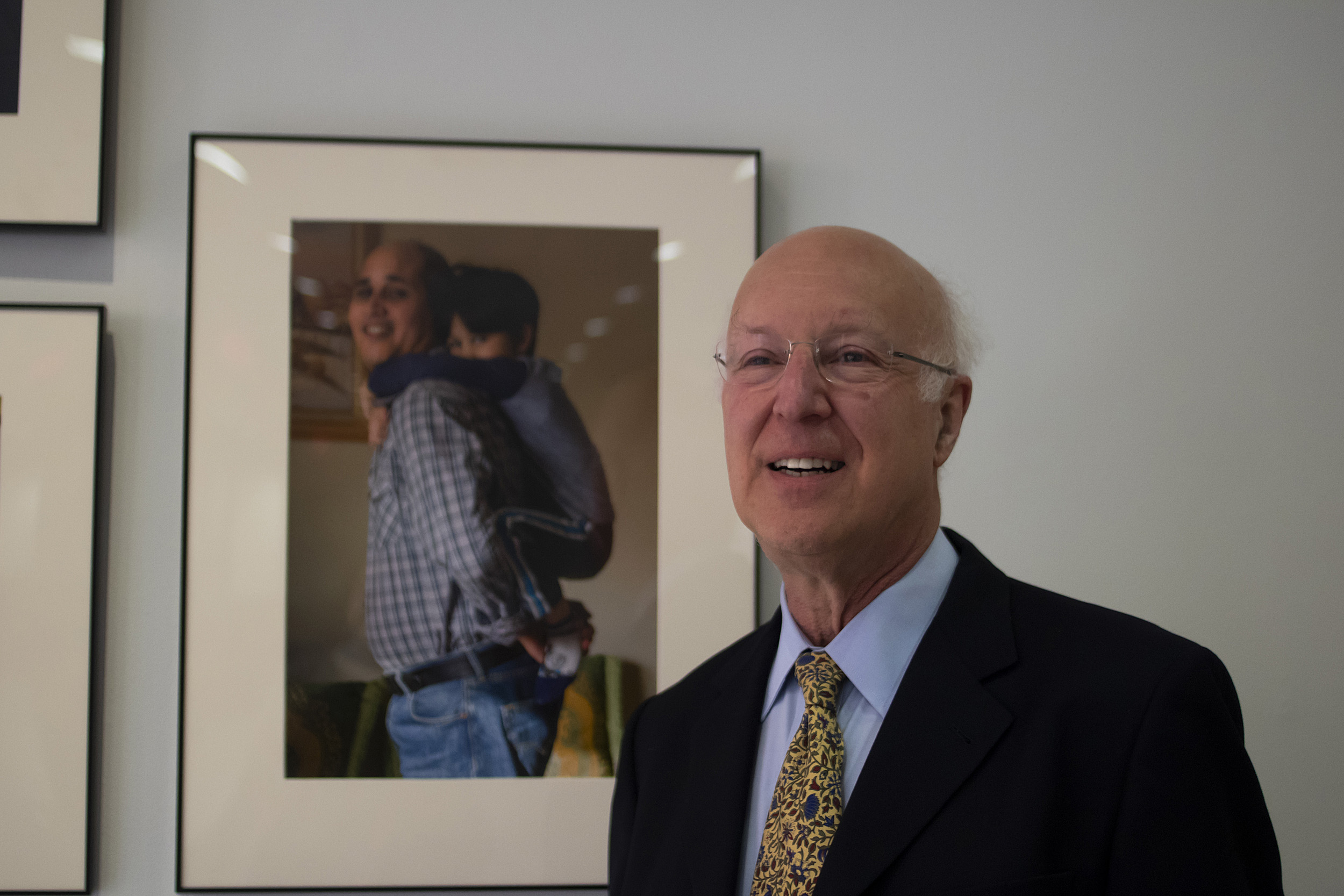

Julian Fisher, a pediatrician and neurologist on the Harvard medical faculty at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, worked over an 18-month period photographing and interviewing middle-class families.

Photo by María F. Sánchez

Stuck in the middle with you

A neurologist explores Massachusetts to tell stories of the middle class through photos

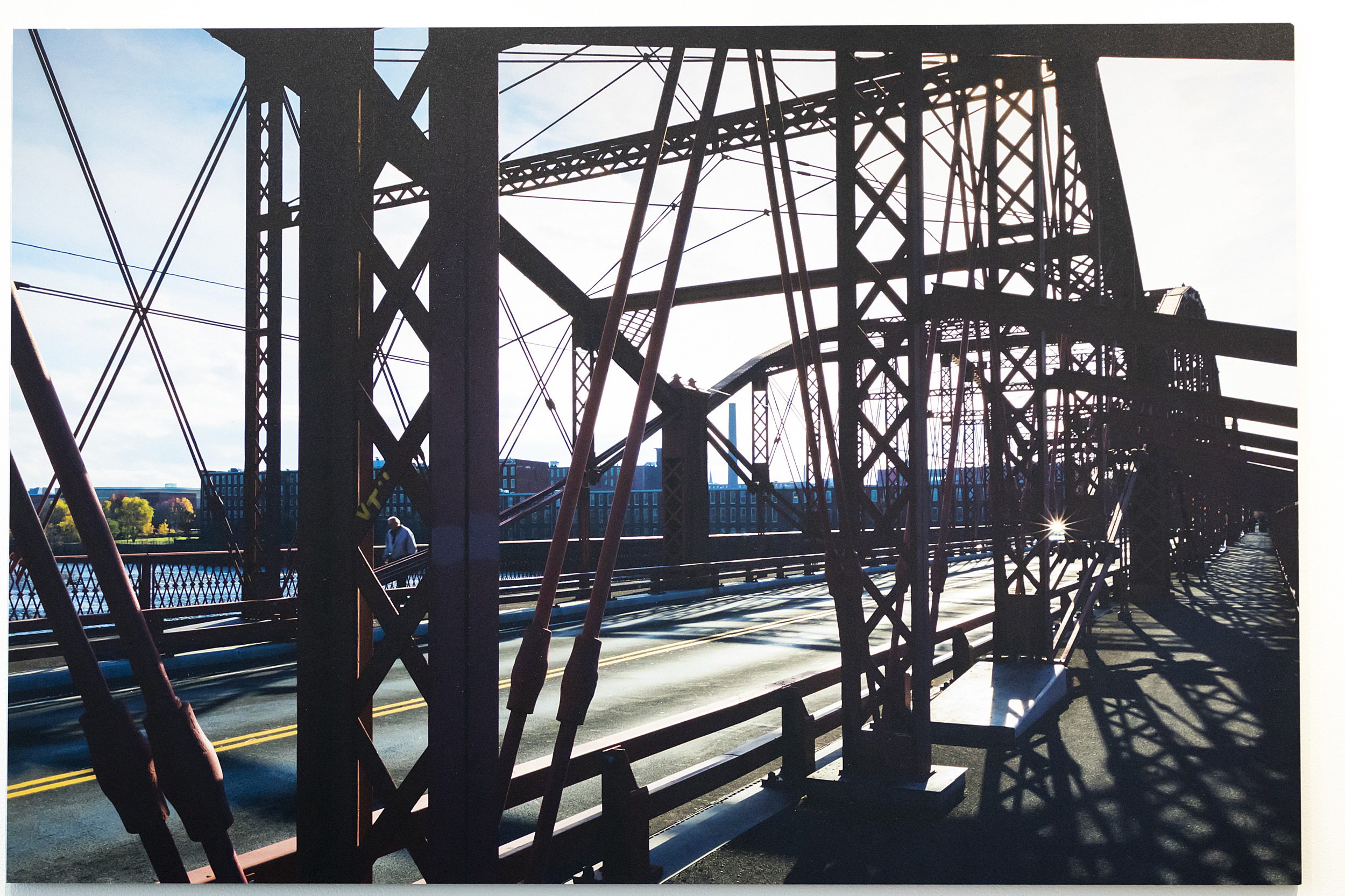

When Julian Fisher took his camera to Lowell, Mass., to document the struggles of middle-class Americans, he stopped to photograph a man crossing a bridge. Behind the bridge, visible between the metal girders, stood the city’s historic textile mills, now luxury condos.

In the day, this man could have worked in the mills, said Fisher, a neurology instructor at Harvard Medical School. Today, he now probably could not afford to live in them.

That photo is one that Fisher uses to tell the story of “Trapped in the Middle: The Effect of Income Inequality on the Middle Class in America,” an exhibit on display at the Japan Friends of Harvard Concourse Gallery in the GCIS Building until April 26.

Fisher’s 18-month process to seek out middle-class families and individuals willing to tell their stories began in late fall 2014. He stayed local, mainly exploring the towns surrounding Brookline, where he lives.

“You don’t have to look very far to find the middle class; they’re here,” he said.

Inspired by Walker Evans’ photographs of sharecroppers in the 1930s, the issues raised by the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011, and the work of economist Joseph Stiglitz, Fisher defined the categories that he wanted to examine. The middle class, he said, is defined not only by how much money a household makes, but also by “practical goals,” including housing, transportation, health care, and education — all of which have gone up in cost, while the buying power of the American dollar declined.

“I wanted to find people who had stories to tell about how they were treading water,” Fisher said. “They have to work harder or give up something to stay where they are.”

Fisher found his subjects through a series of connections: tradespeople with whom he did business, neighbors, and mutual acquaintances. People opened their homes and their lives to him for an hour or two, and he photographed them helping their children with their homework, walking their dog, going to work.

Two photographs on display as part of the exhibit.

Photos by María F. Sánchez

It was a challenge to relay his message through photos, and Fisher said he needed to think on his feet to find the settings to best tell the story.

“I felt like I was photographing ghosts,” he said. “Concepts are abstract, pictures are literal.”

After the photos were taken, he showed them to his subjects, turned on a recorder, and said: “Tell me about this.” Though the recordings did not become part of the final product, he used their words as evocative captions to further illustrate their stories.

“Everybody felt a certain degree of stress,” Fisher said. “What the prior generation had promised would not be achievable. … There was also a subtle disappointment; promises made are not going to be promises kept.”

The subjects’ names and towns are not included in the exhibit, as Fisher wished to maintain their privacy and anonymity. He also wanted the photographs to be universal, and for any viewer to be able to relate to them.

“I’ve always admired the role of photojournalism and its ability to change society. In the back of my mind, I didn’t end up going into it as a career and I ultimately regretted it,” he said. “It was a good experience to devote myself to a love from long ago.

“Income inequality is more pervasive and broad-based and maybe a greater problem for the future of the country than anything else we’re facing, other than climate change,” Fisher said. Paraphrasing Stiglitz, he added: “A middle class under threat is a threat to democracy itself.”