Framing the Caspian Sea

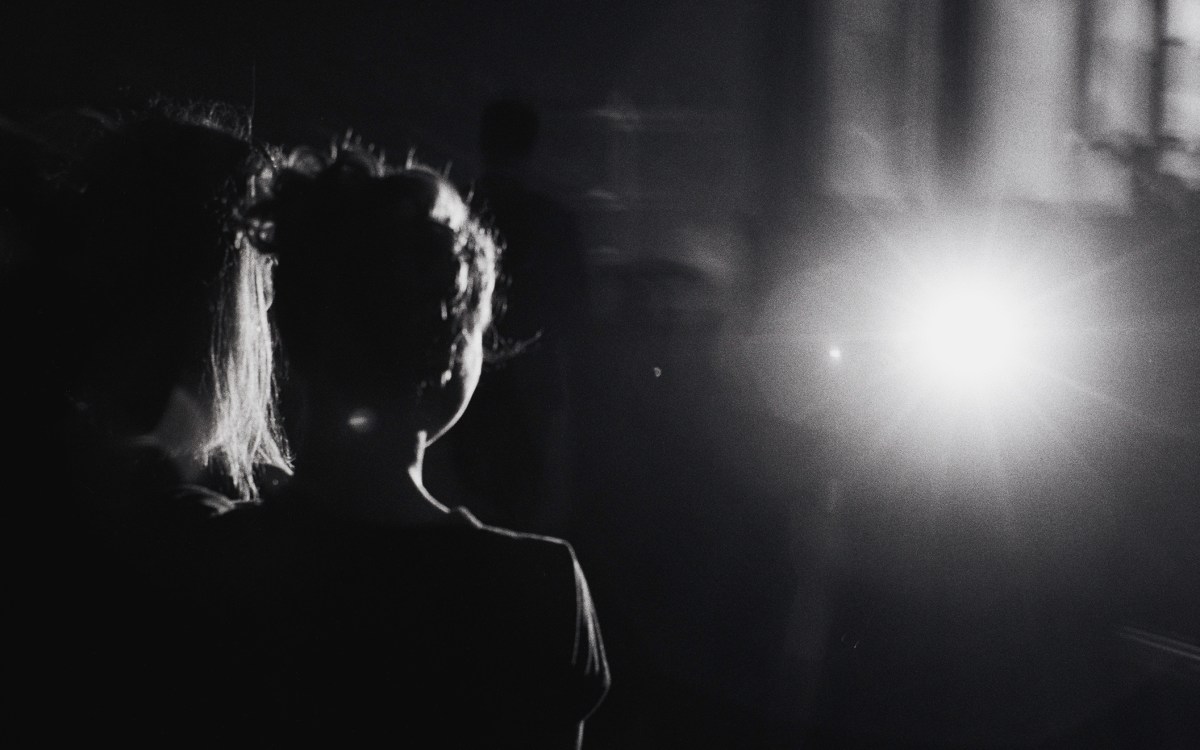

The “Door to Hell.” In 1971, Soviet geologists were drilling in the Turkmen desert when the land gave way beneath them, leaving a 70-meter-wide, noxious gas–emitting crater. They ignited the gas to try to burn off the excess, but the crater has been ablaze ever since. Darvaza, Turkmenistan, 2012.

Photos by Chloe Dewe Mathews

Photographer documents the region through the lens of the area’s natural resources

In 2010 a 10-month hitchhiking trip from China to Britain took photographer Chloe Dewe Mathews to a part of the world she’d never seen. Now she is taking others there with her photographs.

Backed by the Peabody Museum’s Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography, Dewe Mathews returned to the five countries bordering the Caspian Sea between 2010 and 2015, documenting on film the culture, customs, and inhabitants of the area, where deep reserves of oil, gas and other natural resources are inextricably linked to life.

The photos from those travels became the subject of Dewe Mathews’ award-winning book “Caspian: The Elements,” published in 2018 by Peabody Museum Press and Aperture. An exhibition of the same name featuring close to 30 of her evocative images will be on view Saturday through Feb. 7, 2020, at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology.

“I just became very interested in that area, wandering up and down taking photographs of people relating to the sea, coming to this body of water for various reasons,” said Dewe Mathews, whose research-intensive documentary projects often reflect people’s relationship to the landscape. Her work matches the mission of the Harvard fellowship — named in honor of the late author, anthropologist, and documentarian Robert Gardner — to help an established photographer “create and subsequently publish through the Peabody Museum a major book of photographs on the human condition anywhere in the world.”

While traversing Iran, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Russia, and Iran, Dewe Mathews let the elements guide her lens. Struck first by the region’s abundance of oil and gas, she initially sought out “unexpected stories” that could help explain “the effects and consequences of this great potency in the region.” A type of brutal beauty defines much of what she found. Haunting pictures from Naftalan, Azerbaijan, show men and women bathing in crude oil at the local sanatorium, a practice said to carry medicinal benefits.

Her picture of the “Door to Hell,” a giant, molten hole in Darvaza, Turkmenistan, is both dazzling and disturbing. Geologists drilling in the Turkmen desert allegedly created the fiery crater in 1971 when the ground beneath their machine collapsed. Engineers set it ablaze to stop the release of poisonous gas. The fire they thought would quickly exhaust itself has been burning ever since. Ghostly shots taken in the necropolis Koshkar-Ata, Kazakhstan, depict migrant workers, their faces covered to protect them from the sun’s glare, crafting mausoleums for the oil-rich departed in crypts once reserved for local saints.

A sturgeon swims in the pond at the Ramsar Palace Museum and botanical gardens, Ramsar, Iran, 2015. In Turkmenistan, the foreign ministry has expressed plans to transform the luxury beach resort of Awaza into a “Turkmen Las Vegas,” 2012.

Later, Dewe Mathews trained her camera on water, uranium, salt, and rock to uncover other untold stories. Her photographs vividly speak to the complex relationship the residents have with their environment, depicting the sacred peak and popular pilgrim destination Besh Barmag, in Azerbaijan; a dramatic canyon in Balkanabat, Turkmenistan, once covered by the Caspian Sea; a hot spring in Ramsar, Iran, whose surrounding walls were built with local, uranium-rich stone; and a series of shots tracing life along the Volga, the longest river in Europe, which flows through Russia and empties into the Caspian Sea.

“Dewe Mathews’ luminous photographs offer views of people and lands that are striking, even startling,” writes Jeffrey Quilter, the museum’s William and Muriel Seabury Howells Director, in the book’s preface. “They are at once celebratory of the human spirit and despairing in their stark record of what we humans do to ourselves and to our world. They are beautiful and terrifying and always enthralling.”

Beach cafe with soldiers, Lankaran, Azerbaijan, 2010; a Zoroastrian bride in Tehran, Iran, 2015.

“[Dewe Mathews’ photographs] … are at once celebratory of the human spirit and despairing in their stark record of what we humans do to ourselves and to our world. They are beautiful and terrifying and always enthralling.”

Jeffrey Quilter, in the preface for ‘Caspian: The Elements’

Bathers at the Ishker hot springs in Ramsar, Iran, where the walls around numerous medicinal baths were built with local stone, and the healing benefit of the water is sometimes attributed to this radioactive building material (2015). A young woman poses before entering the icy water in Astrakhan, Russia, 2012.

For the Harvard show Dewe Mathews played with perspective and scale. Enlarged images from the book line the gallery’s walls, offering viewers a visceral connection to her underlying themes of rock, water, and oil. “There’s narrative, there’s focus on these specific stories,” said Dewe Mathews of the framed images in the exhibition, “but there’s also a moment to indulge in the beauty of these materials themselves through these large murals.”

For Dewe Mathews, the show’s opening has added resonance because it arrives so soon after Earth Day. Like countless others, the artist said, she is deeply concerned for the planet’s future.

“Many of the pieces do show this kind of almost scarred landscape or the human hand on the landscape, and I think that that’s really important to reflect on,” she said. “I think what art and photography can do really well is pose questions and open up a slightly more subtle debate — and I would hope that is what these photographs do.”

The exhibit at the Peabody will remain on view through Feb. 17, 2020.