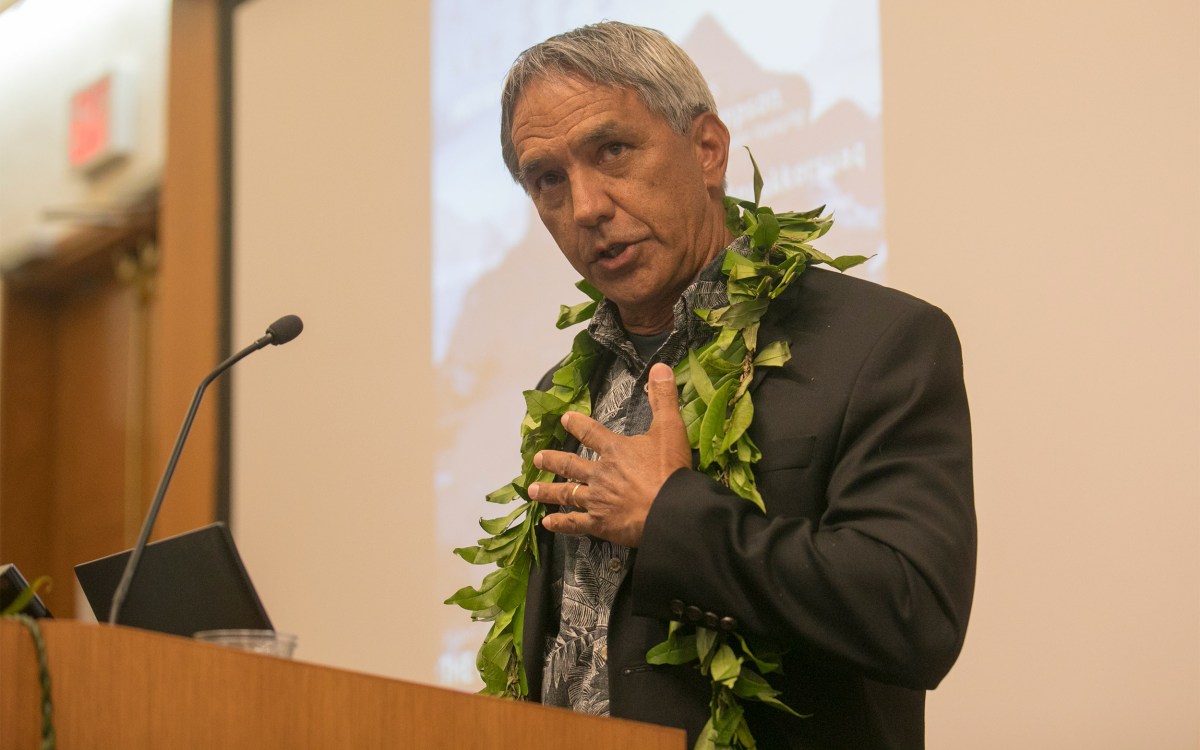

Shaman Davi Kopenawa speaks about the plight of his tribe, the Yanomami, and the implications for the rest of the world.

Reuters/Luke MacGregor

‘We can do our part to stop the destruction’

Yanomami leader and shaman Davi Kopenawa talks about climate change and the rain forest in advance of conference

Known as “Brazil’s Dalai Lama of the Rainforest,” Davi Kopenawa is a shaman and leader of the Yanomami people, an indigenous tribe in the Amazon.

His work to protect his tribe’s forest home from invaders and illegal gold miners has been recognized by the United Nations Environment Programme and by the Brazilian government, which awarded him the Order of Cultural Merit in 2015. He has also won accolades from royalty such as the King of Norway, who visited him in his village in the jungle.

Kopenawa is one of three keynote speakers who will take part in “Amazonia and Our Planetary Futures: A Conference on Climate Change,” a conference May 7 and 8 sponsored by the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard.

The Gazette spoke to Kopenawa via Skype about his people, the effects of climate change in the Amazon, and the need to protect the rainforest. He spoke in Portuguese from Boa Vista, a city in the Amazon region, nearly 4,000 miles away from Rio de Janeiro.

Q&A

Davi Kopenawa

GAZETTE: What message are you bringing on behalf of the Yanomami people to the conference on the Amazon rainforest and climate change?

KOPENAWA: First, let me say thank you for the opportunity to have this dialogue. My people, the Yanomami, have lived in our ancestral homeland, the Amazon rainforest in the northern region of Brazil, for many centuries. In our language, Yanomami means “the people of the forest.” The forest takes care of us; it keeps us healthy, it gives us food, fresh air, and clean water. We believe we were put in a sacred place to be protected by the forest, and that’s why we want to protect it. There are 26,000 people living in Yanomami land, and over the past three decades, we’ve been suffering the impact of not only climate change, but also the invasion of garimpeiros [informal gold miners], who are destroying our trees and polluting our rivers. We’re also suffering from the indifference of the Brazilian government, which does very little to protect our land and our people from invaders.

I’m excited to come to Harvard. I’d like to talk to young and old people, students and professors, men and women, and anybody who wants to talk and listen. I’d like to talk to people and make them aware of the threats that climate change poses to the lives of the Yanomami and everybody.

GAZETTE: How are the Yanomami people being affected by climate change? What changes have you seen in the Amazon rainforest?

KOPENAWA: We know that not only the Yanomami people are being affected by climate change. It’s the whole planet — the cities, the countryside, and the forest that are being affected. What we’ve noticed is that in the summertime, it gets very hot — hotter than years before; we see the rivers getting dry and the fish dying. In the past, it used to rain more; now rains are less frequent. And when it rains, we see the pollution covering the mountains. Our health is being affected. Our people get sicker and sicker. We’re also worried about the Brazilian government, which is destroying the forest to grow soy.

Climate change is harming the planet because governments all over the world lack the commitment to protect the Amazon and the world’s natural reserves. Instead, they encourage companies to explore for coal, petroleum, and natural gas. We didn’t used to see pollution in the Amazon. We worry that the smoke from pollution is affecting the Amazon rainforest, the lungs of the planet. We also worry about how we’re going to have a dialogue with those who are destroying our resources, how we can ask them to stop the destruction.

GAZETTE: You have traveled all over the world bringing your message. What has been the response from the public?

KOPENAWA: I have spoken to many audiences about the importance of working together to take care of the planet, and my experience is that there are certain people who don’t want to listen and don’t want to believe what climate change is doing to the planet. What I’ve seen is that there are some people who listen, but those with power — authorities and government officials — don’t want to listen. But I’ll continue talking because it’s important to care and preserve the beauty of the Amazon rainforest. It’s already being destroyed, but we can do our part to stop the destruction. If the rainforest dies, if water dries up, poverty and disaster will hit us.

We found support from Survival International, an organization in England that works to defend indigenous peoples all over the world, and from the United Nations. They helped us with our campaign to obtain a legal decree from the Brazilian government that recognized the Yanomami as the rightful owners of our land. That was in 1992. We achieved that recognition because of the international support we had. But we need more support to make the Brazilian government enforce the law and protect us from those who are invading our land.

I traveled to all those places as an ambassador of the Yanomami people. It was good that I chose this path because it brought recognition to the Yanomami. Now the world knows the Yanomami people.

“The forest takes care of us; it keeps us healthy, it gives us food, fresh air, and clean water. We believe we were put in a sacred place to be protected by the forest, and that’s why we want to protect it.”

GAZETTE: What was your impression of the places you have visited?

KOPENAWA: I’ve visited many places. I won a prize and was invited to England, then I went to the United States to visit the United Nations. I’ve also been to France, Germany, Greece, Norway, Portugal, Canada, and the Canary Islands. But it makes me sad when I visit a country and learn it doesn’t have a forest. Most cities have lots of people, lots of cars, lots of noise, lots of pollution, and lots of trash. I missed seeing scarlet macaws in those big cities. And the rivers and the oceans are so dirty and polluted with trash and plastic. Everything I saw in the cities makes me think that life in the cities must be very difficult. I go to the cities to fight for the rights of the Yanomami people and to talk to government officials who have offices in the cities. But when I’m in the city, I have lots of nostalgia for my family, my people, my hometown, and sometimes I wonder why I chose this path, why I became an activist to defend the rainforest and the rights of the Yanomami people. I don’t belong in the city. I belong in the forest.

GAZETTE: When you go back to the forest after those trips to the cities, what’s the first thing you do?

KOPENAWA: The first thing I do is rest. I take off my city clothes, sneakers and pants, put on my slippers and shorts, grab my arrow to hunt and fish, and then I go to the forest.

GAZETTE: Why did you decide to become an advocate for your people?

KOPENAWA: I was a shaman. When I was 25 years old, I became a shaman to heal my people with our traditional medicine, which is based on plants and herbs from the forest. But I decided to start fighting for our rights around 1986 with the arrival of the first gold miners in our territory. They came to our territory looking for gold and destroyed trees and polluted our rivers with mercury. I saw many people dying because of the diseases brought by the invaders. I began noticing my people’s pain. I decided to enter the fight to defend and protect my people. The government also brought a lot of suffering to my people. They destroyed the forest to build highways inside the Yanomami land.

GAZETTE: How did you train to become a shaman?

KOPENAWA: I wanted to become a shaman to help people. A shaman trained me and helped me learn about our traditional medicine and about the xabori, the spirit of the forest. I perform rituals and healing with a tree called yakoana. That’s how we cure ourselves; it’s our tradition. As part of the initiation to become a shaman, I was in the forest for a whole month by myself. I had to learn how to listen to the forest, the sun, the moon, the rain, and the heart of the earth. That was my first training as a shaman.

GAZETTE: To be an indigenous or civic leader in Brazil is risky. Many have been killed, including environmental activist Chico Mendes, who was assassinated more than 30 years ago. Are you afraid of being a target?

KOPENAWA: Yes, I’m afraid. I’m afraid of white men who kill indigenous people with firearms. I’m afraid of firearms. I’m not afraid of using our mouths to argue. We can talk, protest, denounce, but we don’t have to use firearms. I know this is very dangerous, but I chose this path to defend and protect my people. I’ve been fighting for our rights for many years and I’ll continue fighting for the rights of the Yanomami. I’ll continue fighting until the end of my days. We have to protect the forest because we depend on the forest. Our children and grandchildren and future generations need the forest.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

“Amazonia and Our Planetary Futures: A Conference on Climate Change,” will be held May 7 and 8 at Tsai Auditorium, CGIS-South, 1730 Cambridge St., and will be livestreamed on Facebook.