The bronze lion statue at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies casts a shadow in the courtyard. Harvard’s Adolphus Busch Hall was funded by the co-founder of the Anheuser-Busch brewing company, who was a German immigrant.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

The long, deep ties between Harvard and Germany

Over more than a century, the connections have spanned everything from curriculum reform to art collections to trans-Atlantic fellowships

In 1971, Guido Goldman, founding director of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies (CES), walked into a meeting with West Germany’s then-finance minister, Alex Möller, hoping for a gift to help support the center. He left with a sweeping offer that he couldn’t have imagined.

“I was kind of blown away,” said Goldman, recalling that meeting. He had envisioned a $2 million gift to the center, then known as the Western European Studies program, as a way for Germany to say thanks for the aid that the U.S. had given it in the years following the world wars. “I said to the finance minister, ‘It’s just my feeling that Germany should say thank you for all this assistance,’” Goldman said. “After I made my little speech in German — because he spoke no English — he said, ‘I completely agree with you, and we will do it, and you will help us design [the initiative].’”

Goldman, astonished, inquired, “Could you tell me in what dimensions of financing you have in mind?” Möller replied, “‘I have in mind a gift of 250 million marks’ — which was $65 million.” In the end, $1 million of the gift went to the CES and the rest became the German Marshall Fund of the U.S., one of the most important trans-Atlantic organizations.

Yet the moment between Goldman and Möller was just another part of the longstanding history of connections between Harvard and Germany.

In the latest of these links, German Chancellor Angela Merkel will soon be the principal speaker at Harvard’s 368th Commencement, the fourth postwar German chancellor to do so. She’ll also receive an honorary degree from the University, as have five chancellors before her: Konrad Adenauer (1955), Willy Brandt (1963), Ludwig Erhard (1965), Helmut Schmidt (1979), and Helmut Kohl (1990). German President Richard von Weizsäcker was the speaker in 1987.

In advance of Merkel’s visit, the Gazette surveyed a number of key developments between Germany and Harvard during the 19th and 20th centuries, which ultimately speak to efforts in U.S., German, and European history to encourage trans-Atlantic relations and academic study. The connections have included art collections, fellowships and scholarship programs for German students and professionals to study at Harvard, and research and study-abroad opportunities for Harvard students and faculty to travel to Germany.

A patron views Max Beckmann’s “The Actors” at Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Coming together through art

One of the most notable links started in the later 19th century, when Harvard looked to the German university model for inspiration.

By the mid-1800s, German universities were among the most admired in the world, so respected that students who studied at Harvard would often go to Germany for postgraduate studies. At the time, Harvard had many German professors — Kuno Francke joined the German department in 1884; Hugo Münsterberg began teaching philosophy in 1891; the philologist H.C.G. von Jagemann arrived on campus in 1897 — and many Harvard professors had spent a year or more studying in Germany.

In his 1869 inaugural address, Harvard President Charles W. Eliot announced changes he intended to make that were modeled in part on the German system and were then-novel ideas in the U.S.: Introducing an elective system so students could choose some of their own courses, expanding the library, revamping the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and creating professional schools that would go on to become the School of Business and the Graduate School of Design.

Eventually, Francke, Münsterberg, Jagemann, and two other German faculty members — George Bartlett and Hugo Schilling — began working to bring German art to Harvard, leading to creation in 1901 of the Germanic Museum. It was the first museum in North America dedicated to the study of the countries of Central and Northern Europe, including Holland, Scandinavia, Switzerland, and Austria, and it made Harvard a key link in the relationship between the U.S. and Germany at a time when relations between the two nations didn’t go far beyond immigration.

The following year, German Kaiser Wilhelm II made a large pledge of German art and architecture replicas to the museum, some of which were monumental in size and cultural significance, such as the 13th century Golden Portal from the Church of Our Lady in Freiberg. In return, Harvard hosted Wilhelm’s brother, Prince Henry, in 1902 and presented him with an honorary degree. During the ceremony, the prince read from a telegram the Kaiser sent congratulating him on the degree, calling it the “highest honor which America can bestow.”

In 1901, Kaiser Wilhelm II made a large pledge of German art and architecture to Harvard, including a replica of the 13th century Golden Portal from the Church of Our Lady in Freiberg, which stands in Adolphus Busch Hall.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Despite such moments of goodwill, however, relations between the nations soured as the First World War broke out, and by April 1917 the U.S. had joined the allies in the fight against Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria. That dampened the opening of the museum’s new home, Adolphus Busch Hall, which was funded by the co-founder of the Anheuser-Busch brewing company, who was a German immigrant. The building was completed that same year but did not open until 1921 because of the political climate (though the official reason given was “lack of coal” for heating).

The museum would close again during World War II — and the U.S. Army used the building. During the war, arts funding dried up and by the time the troops moved on the Germanic Museum was nearly broke. Edmée Busch Reisinger Greenough, one of Adolphus’ 13 children, helped the museum get back on its feet with donations totaling $205,000 in 1948 and 1949. The museum was renamed the Busch-Reisinger Museum in honor of her contributions.

Almost 30 years later, in 1987, Harvard officials who worried about the lack of climate control in Busch Hall moved the majority of the artwork to temporary quarters in the Fogg Museum while Werner Otto Hall, an addition to the Fogg funded by another German entrepreneur, was being built. The collection moved to Otto Hall when it opened in 1991. Busch Hall, now home to CES, continues to house much of the founding collection of medieval art plaster casts.

While its ties to the German government aren’t as direct as they were in its early years, the museum remains true to its mission, with particularly strong holdings of Vienna Secession art, German expressionism, and Bauhaus-related materials.

“The museum came out of this very particular moment between Harvard and Germany at the end of the 19th century,” said Lynette Roth, the Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum. “What I always try to emphasize now is not to forget that history but also try and show how the museum has grown and changed.”

Rebuilding connections

During much of the second half of the last century, Germany worked with Harvard to rebuild its relationship with the U.S.

Twenty-five years to the day after U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall announced the European Recovery Program — commonly known later as the Marshall Plan — at Harvard’s 1947 Commencement, then-Chancellor Brandt announced the creation of German Marshall Fund during a 1972 convocation at Sanders Theatre, again making Harvard a key locus of U.S. and German relations.

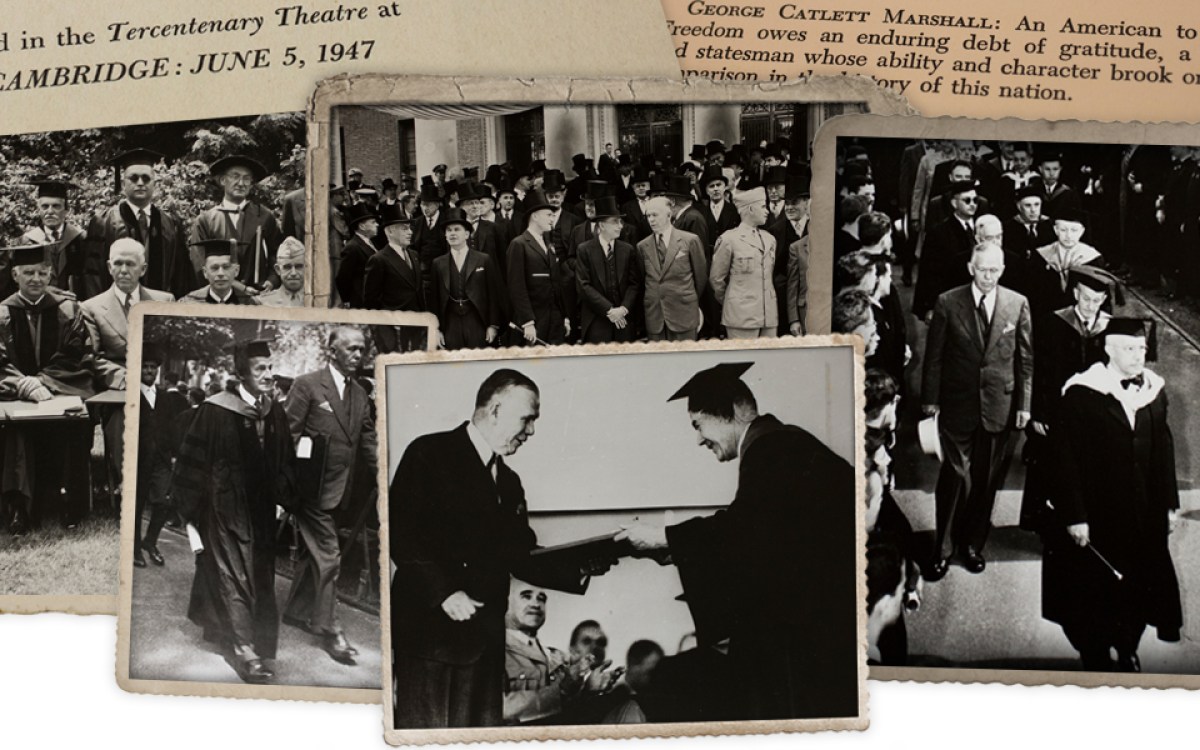

In 1947, Secretary of State George C. Marshall (left) receives an honorary degree at Harvard’s Commencement, where he announced the European Recovery Program. In 1972, then-Chancellor William Brandt announced the creation of German Marshall Fund at Harvard.

Harvard University Archives; German Marshall Fund

In 1902, Germany’s Prince Henry is seated next to Harvard President Charles W. Eliot on their way to Memorial Hall; in 1963, President John F. Kennedy delivers his “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech in West Germany.

“A History of the Germanic Museum at Harvard University” by Guido Goldman, Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies; John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Much of the work between Germany and Harvard happened out of CES, founded in 1969 by Goldman ’59, Ph.D. ’69, and Buttenwieser University Professor Stanley Hoffmann, who was who was born in Vienna and escaped Paris just days before Germany’s invasion. Throughout its history, the center has been known for having a strong focus on the study and betterment of Germany and all of Europe. The establishment of Krupp Family Foundation–supported fellowships and a professorship of European studies, part of a $2 million gift meant for “the strengthening of relations between America and Europe,” was the first partnership between an American university and a private German foundation. The Program for the Study of Germany and Europe produced research papers, lectures, conferences, and workshops on the study of contemporary Germany and Europe. And the Konrad Adenauer Fellowship sponsors Harvard graduate students interested in studying and researching at German universities.

CES also manages the John F. Kennedy Memorial Fellowship, a hallmark of trans-Atlantic dialogue between American and German scholars. It was launched in 1967 to honor the slain president, a 1940 College graduate. In 1963, Kennedy made a landmark visit to then-West Germany, giving his famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech before a half-million residents in support of freedom. Five months later, two days after Kennedy’s assassination, the cabinet of West German President Heinrich Lübke met to develop a plan to commemorate the visit. That turned into the fellowship, which was funded by the government and private donations from German industry to allow fellows to spend an academic year at Harvard. The program has brought more than 100 German social scientists, politicians, and journalists to the University, and in 2017 expanded to include non-German scholars from the European Union.

“It was really meant to be a trans-Atlantic bridge of academic and cultural exchange,” said Elaine Papoulias, executive director of CES. “Programs like this are really important when, diplomatically, countries bilaterally hit low points. The recipients of the fellowship who come really develop quite an attachment academically and personally to the community here. The community here becomes their second family.”

At the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), another program was started in 1983, said Mathias Risse, the Lucius N. Littauer Professor of Philosophy and Public Administration and director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. Called the McCloy German Fellowship, the program recruits about six German masters’ students a year to study at HKS. It was named after John J. McCloy, the first civilian high commissioner of occupied Germany, and has more than 200 alumni and an annual conference in Berlin.

“It’s a program that was always built around this idea that Germans would come to America, would understand America better, would go back to Germany, and would be able to communicate what America is all about,” Risse said.

Through high-profile programs such as these, Harvard and its experts remained steady players in German and U.S. relations. They are often called when new initiatives arise across the Atlantic. Take, for example Urs Gasser, executive director of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society and a professor of the practice at the Law School. Last year he was tapped to become a member of Merkel’s German Digital Council, which advises her government on topics like the role of data and digitizing systems and works on projects such as streamlining applications. “If Angela Merkel calls you and says, ‘Look, I need your advice,’ you’re likely to say yes,” Gasser said.

Beth Simone Noveck ’91, A.M. ’92, is also on the council. She is a law professor at New York University and served as New Jersey’s first chief innovation officer, and from 2009‒2011 was the deputy chief technology officer for the U.S.

Guido Goldman (left) and Karl Kaiser speak at Busch Hall.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Another example is Karl Kaiser, senior associate for the Project on Europe and the Transatlantic Relationship at HKS’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Since the 1970s, he’s been a member of the Council of Environmental Advisors of Germany. Kaiser has served as an expert member for several commissions of the German Parliament on issues like the expansion of the European Union. He was also a political advisor to Chancellors Brandt and Schmidt, and to Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, in the Kohl administration.

Goldman, along with helping establish the German Marshall Fund, Kennedy Fellowship, and McCloy Fellowship (with Kaiser), was also asked by the German government to help create the German Academic Exchange Service’s Centers of Excellence. They were founded in 1990 at Harvard, Georgetown University, and the University of California, Berkeley, to encourage more collaboration in the humanities and social sciences between the U.S. and Europe and to promote the study of Germany.

Continuing cultural exchange

Many of the more recent connections between Harvard and Germany are based on a continuing cultural exchange of ideas in the same vein as the Kennedy and McCloy fellowships. At the Medical School, for example, an immunology program allows students to do a summer rotation at Ludwig Maximilian University and Technical University, both in Munich.

More like this

“It’s an exchange of scientific ideas, a sharing of techniques and teaching methods, and an opportunity for students to learn at a high-level institution from the other side of the Atlantic,” said Ulrich H. von Andrian, the Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Professor of Immunopathology.

Harvard’s Germanic Language and Literature Department offers a similar work-abroad program for students that helps them gain professional experience while exploring German language and culture, said Andreea Florescu D’Abramo, the department administrator. Last year, students interned at companies, nonprofits, and universities in cities including Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Munich.

Harvard College also offers summer programs for students to study abroad in Berlin and Vienna for eight weeks.

The campus is also home to the Harvard Business School Association of Germany e.V., a nonprofit formed in 1997 to support and organize activities for HBS alumni in Germany, and the Council of the German American Conference at Harvard e.V., whose annual conference connects nearly 1,000 American and German leaders in business, politics, and academia to Harvard students who are interested in Germany for panels, speaking programs, and other networking opportunities.

“All these great, like-minded people stay in touch,” said Fabian Baldauf ’17, chairman and founding member. “Over the years, it’s grown into a really powerful network.”