Stonewall then and now

Harvard scholars reflect on the history and legacy of the milestone gay-rights demonstrations triggered by a police raid at a dive bar in Manhattan

Protesters took to the streets in the aftermath of the Stonewall riots in lower Manhattan in the summer of 1969. Stonewall marked a turning point in the gay rights movement.

Leonard Fink/The LGBT Community Center National History Archive

Michael Bronski wasn’t at Stonewall and doesn’t mind admitting it, unlike many members of the gay and lesbian community of a certain age who, he says, insist they were. The joke is that if everyone who claims they took part in the famous 1969 uprising in lower Manhattan that catalyzed America’s gay-rights movement actually had been there, the crowd, Bronski says with a laugh, “would have filled Yankee Stadium.”

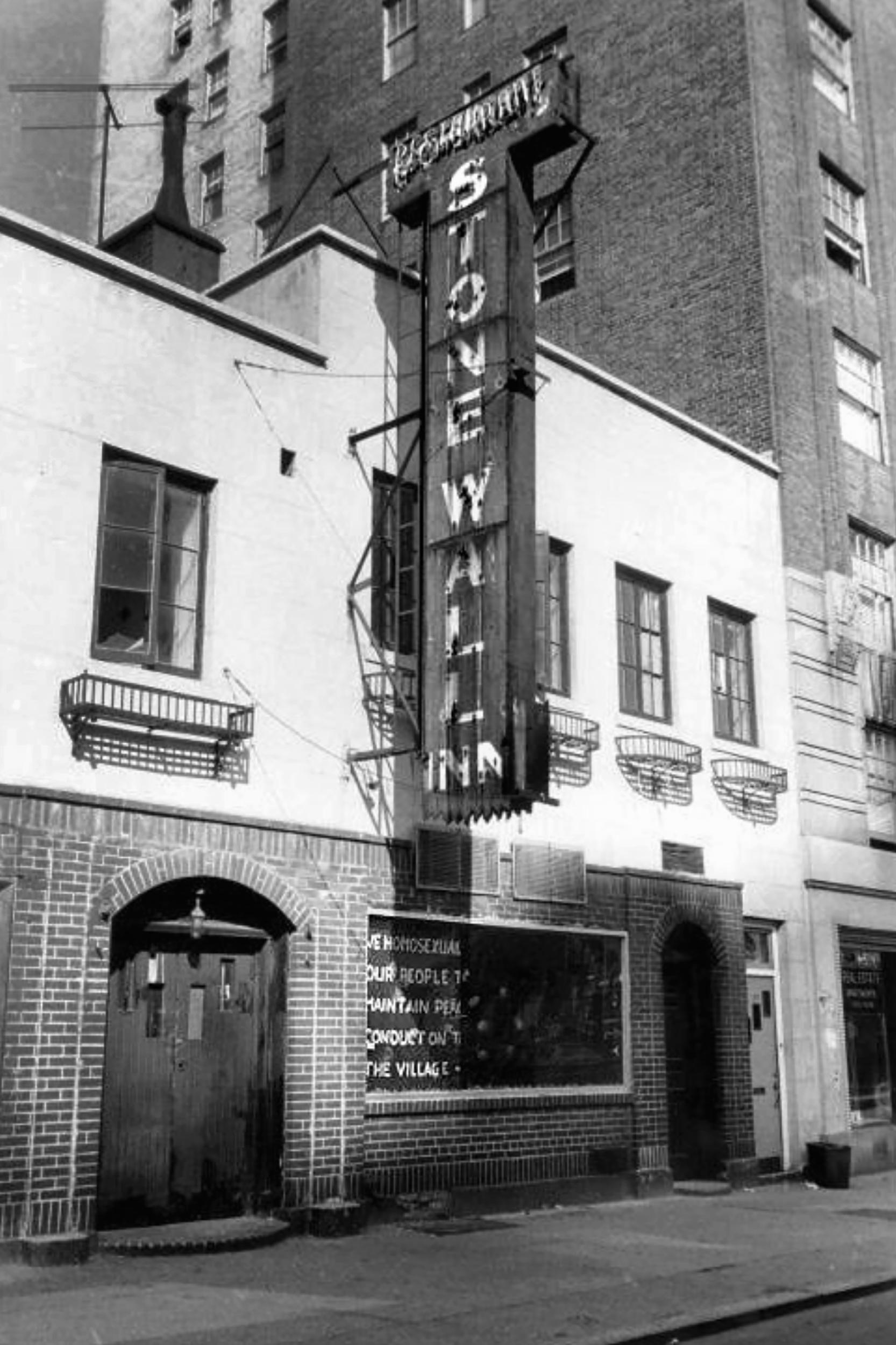

In truth, the crowd that day numbered about 200, at least at first. And they weren’t protesters but mostly patrons of the Stonewall Inn, a popular Greenwich Village gay bar. The trouble started when the police arrived in the wee hours of June 28 to raid the Mafia-run tavern on a trumped-up liquor-license charge. Officers started pushing customers and workers into police vehicles. But instead of dispersing as they had during past routine raids, those who hadn’t been grabbed began cheering those who had. The crowd of onlookers swelled as tourists and neighborhood residents stopped to investigate. Then, according to multiple accounts, a lesbian who was fighting attempts to haul her into a squad car cried out, “Why don’t you guys do something!” The air grew thick with chants — along with bottles and bricks. The officers barricaded themselves in the bar and radioed for back-up as a riot flared. More violent demonstrations shook the neighborhood in the following days.

Today, Bronski, a Harvard professor of the practice in media and activism in Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality, understands why so many claim to have been present at such a pivotal moment in the history of the gay rights movement.

“It really is like the shot heard around the world, or the hairpin drop heard round the world,” he said, a cheeky parody coined in Stonewall’s aftermath of the stanza from “Concord Hymn.” There had been previous riots in the U.S. involving gays and lesbians fed up with routine harassment, but Stonewall, erupting when it did amid protests over the Vietnam War and civil rights and gender equality, marked a decisive break from the more passive sexual-orientation politics of the day, said Bronski, who has written extensively on LGBTQ culture and history.

“It was really like direct action. It was like the radical feminists invading the Miss America contest, or the Black Panthers standing in front of Oakland City Hall with rifles,” he said, and it ran completely counter to the approach of groups such as the Mattachine Society, one of the nation’s earliest gay-rights organizations, that preferred to press for change through legal and political channels. Not long after the Stonewall raid, a message appeared on the boarded-up window of the bar, pleading for the return of “peaceful and quiet conduct on the streets of the village.” It was signed “Mattachine.”

“What’s so amazing is that they would never have thought of doing anything public like that before,” said Bronski. “So literally overnight, Mattachine is forced into making a public announcement with essentially graffiti.”

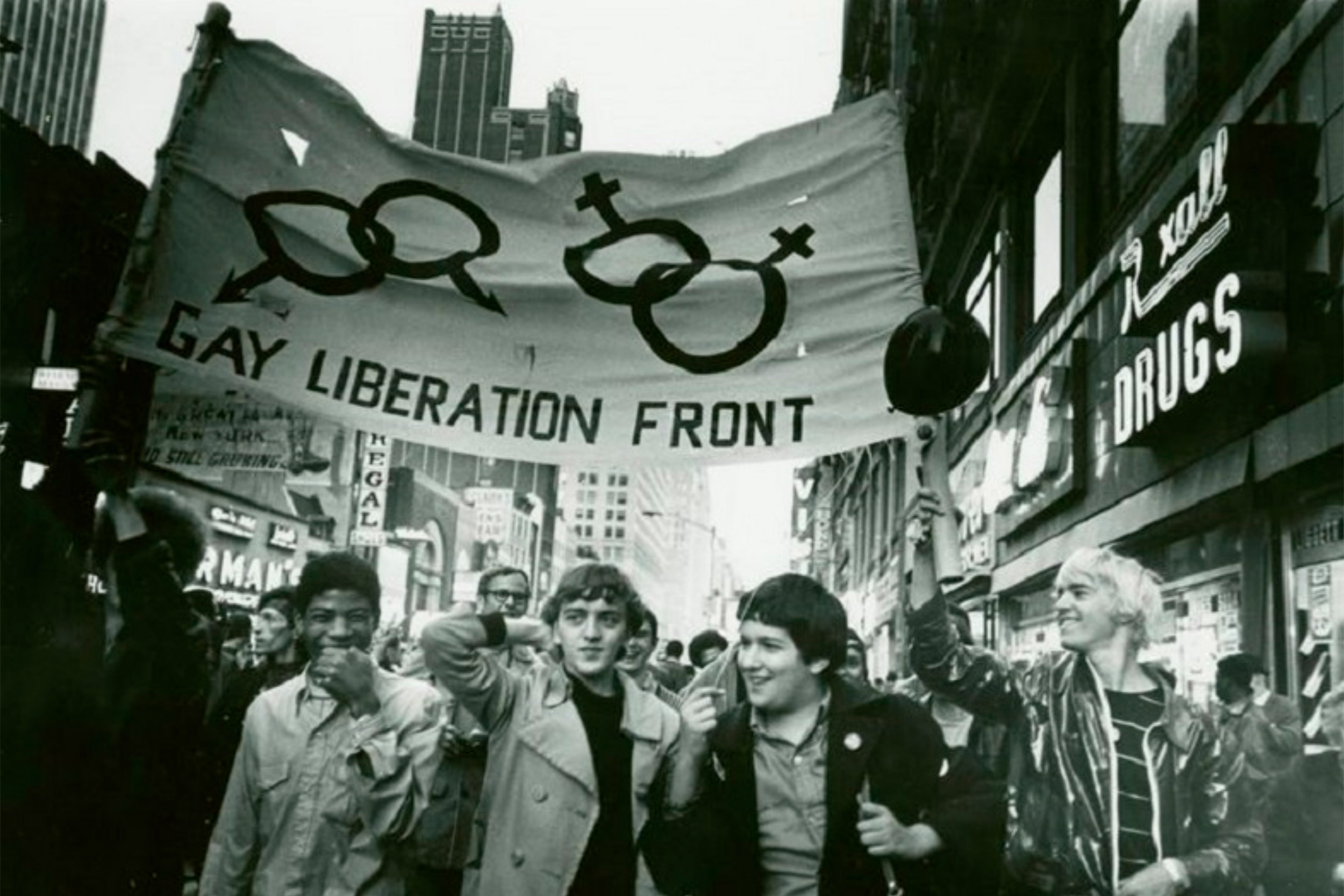

For Bronski, Stonewall represented a “shocking change of consciousness for the world.” And in its wake rose the Gay Liberation Front, a more radical version of the Mattachine Society unafraid to use confrontation to push reform.

But there were other organizations helping drive change. Harvard’s Evelynn Hammonds, chair of the Department of the History of Science, Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz Professor of the History of Science, and professor of African and African American Studies, said that in the years after Stonewall the story of greater visibility for gay people in America was often seen through the lens of gay men. That perspective, she said, overlooks a key connection.

“At the time of what we now call the Stonewall Rebellion, what was also happening was the second wave of the women’s movement. And while there were lots of tensions in some women’s organizations between lesbians and straight women, there was also a great deal of unity, and people were coming together around a shared desire for greater equality for women and gay people,” said Hammonds.

A look at the history

Though their methods may not have been as radical, early so-called homophile organizations — including the Mattachine Society, Janus Society, and Daughters of Bilitis — set the stage for what followed, says Timothy Patrick McCarthy, a lecturer in public policy and core faculty at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard Kennedy School.

“The foundation for the movement that emerges in fuller form in the wake of Stonewall was laid in the decades before in public and private battles, in different organizations, and through the work of many people,” said McCarthy, whose book, “Stonewall’s Children: Living Queer History in an Age of Liberation, Loss, and Love,” will be published by The New Press next year.

Many such groups materialized during World War II and the post-war era in response to the military’s anti-homosexual policies and the paranoid frenzy of the Red Scare. McCarthy points to the “Lavender Scare,” a fear campaign that paralleled Republican Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s investigations into what he considered widespread subversive forces at work in the federal government in the 1950s. While simultaneously trying to expose suspected communists, the Wisconsin senator also targeted suspected homosexuals, arguing that “deviant sexual behavior, like deviant political ideology, were things that made people more vulnerable to blackmailing,” said the Harvard scholar, who recently edited a special issue of The Nation examining Stonewall’s legacy.

McCarthy’s tactics initially garnered widespread support. President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued an executive order in 1953 banning homosexuals from working for the federal government, citing security risk. Thousands lost their jobs because of their actual or perceived sexual orientation. Among them was the man many have called the “Father of the Gay Rights Movement,” Frank Kameny, who received his master’s and doctorate degrees in astronomy from Harvard in 1949 and 1956, respectively. After the Army Map Service fired him as an astronomer in 1957, Kameny unsuccessfully sued the federal government and later devoted his life to fighting for gay rights. Among his many achievements, Kameny, who died at the age of 86 in 2011, was known for founding the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., picketing the White House, contesting the American Psychiatric Association’s categorization of homosexuality as a mental defect, and coining the term “Gay is good.”

The 2011 New York City Pride March honored the legalization of same-sex marriage in New York that year. A Gay Liberation Front march in Times Square in the fall of 1969. Jackie Hormone, among the first to fight the police at Stonewall, is on the right.

Sasha Kargaltsev/Creative Commons; photo by Diana Davies © New York Public Library

Stonewall’s legacy

Hammonds wasn’t at Stonewall either, but the image looms large in her mind thanks in part to the actions of those eager to keep its spirit alive. During the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations in 1969, a young activist called for nationwide demonstrations each June in honor of Stonewall. New York’s first pride parade, named the Christopher Street Liberation Day, was held in June of 1970, just a year after the riots. The march began on Christopher Street where the bar — now a historic landmark — was located, and it ended in Central Park. The event attracted thousands and signaled another important milestone. In the years that followed more cities and towns organized parades in support of gay rights.

“The marches were among the first highly visible public events for people to express their gay sexuality and for allies to have an opportunity to support the gay people in their lives,” said Hammonds, who was a graduate student in Boston in 1976 when she attended the city’s Pride parade and first heard of Stonewall. “The marches also became vehicles for political expression as well, which you could see by the signs that people held up, which made the marches political moments as well as scenes of gay pride. Even local politicians recognized this and slowly, over time, more politicians would join the marches.”

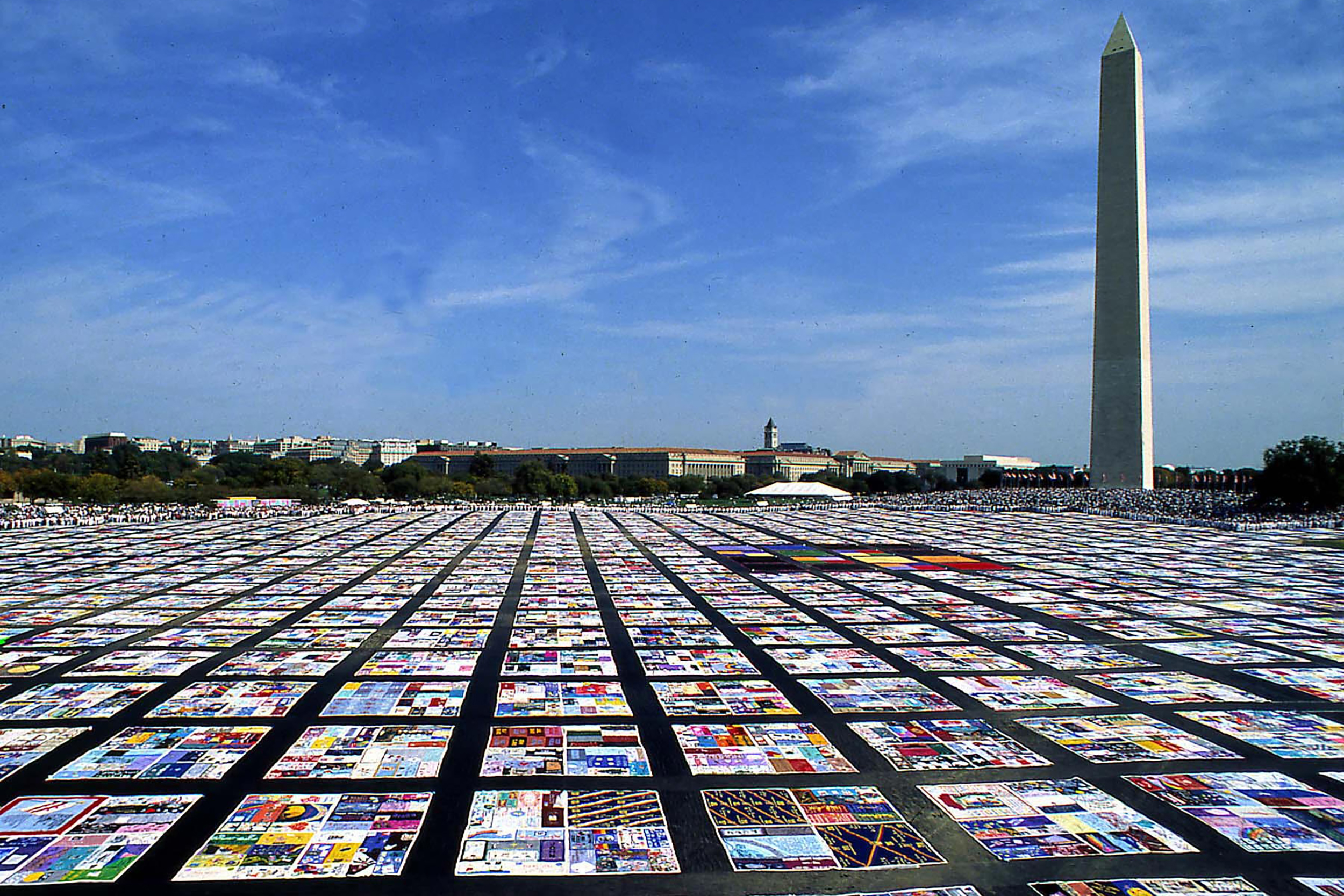

One march in Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1987 left another lasting impact on Hammonds. The event coincided with the first showing of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, a massive patchwork blanket adorned with the names of those who had died. The colorful fabric covered an area on the National Mall larger than a football field and contained 1,920 panels “that captured the beautiful range and diversity of the gay experience with a kind of poignancy and sadness, but also affirmation of gay life that I had never seen before,” said Hammonds.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt on display at the Washington Monument. The massive patchwork blanket was adorned with the names of those who had died.

Credit: National Institutes of Health

The epidemic raised the visibility of the gay community further as more and more people were forced to come out to family and friends, she said.

“When young men began to get sick, a lot of them had to return to the places where they grew up, because some didn’t have anybody to take care of them in the cities where many gay people had congregated,” said Hammonds. “They returned to the small towns, or smaller cities and places where many people in their lives didn’t know that they were gay … of course, not everyone was welcomed home with open arms, but ironically one of the consequences of the epidemic was that more Americans became aware of gay people in their communities.”

Hammonds said she has been shocked at the rapid pace of change she has witnessed over the last 40 years, from attending her first Gay Pride parade to watching the faces of Pride marchers get younger and increasingly diverse to getting married and starting a family.

“We got married the first night you could,” said Hammonds, who arrived at Cambridge City Hall on May 17, 2004, with her partner just after midnight so they could be among the first in the country to be granted a same-sex marriage license. (Cambridge was the first municipality in the country to issue the licenses.) “It was the most amazing thing to come out of the front door of City Hall and see Massachusetts Avenue just filled with people singing and yelling with joy that gay marriage was now legal.”

Still, Hammonds sees difficult times ahead and anticipates “very serious attempts at retrenchment.”

“There appears to be a growing backlash from people who feel that expanding gay rights and rights for transgender people means that heterosexuals have lost something they can never regain. But fortunately the younger generation sees the world differently now. Many have grown up in a world where there is more equality, more acceptance of sexual and gender difference, and they value it, and they are comfortable with it. So those of us who are older have to do whatever we can to support them in holding onto those rights we marched for a long time ago and that we continue to fight for.”

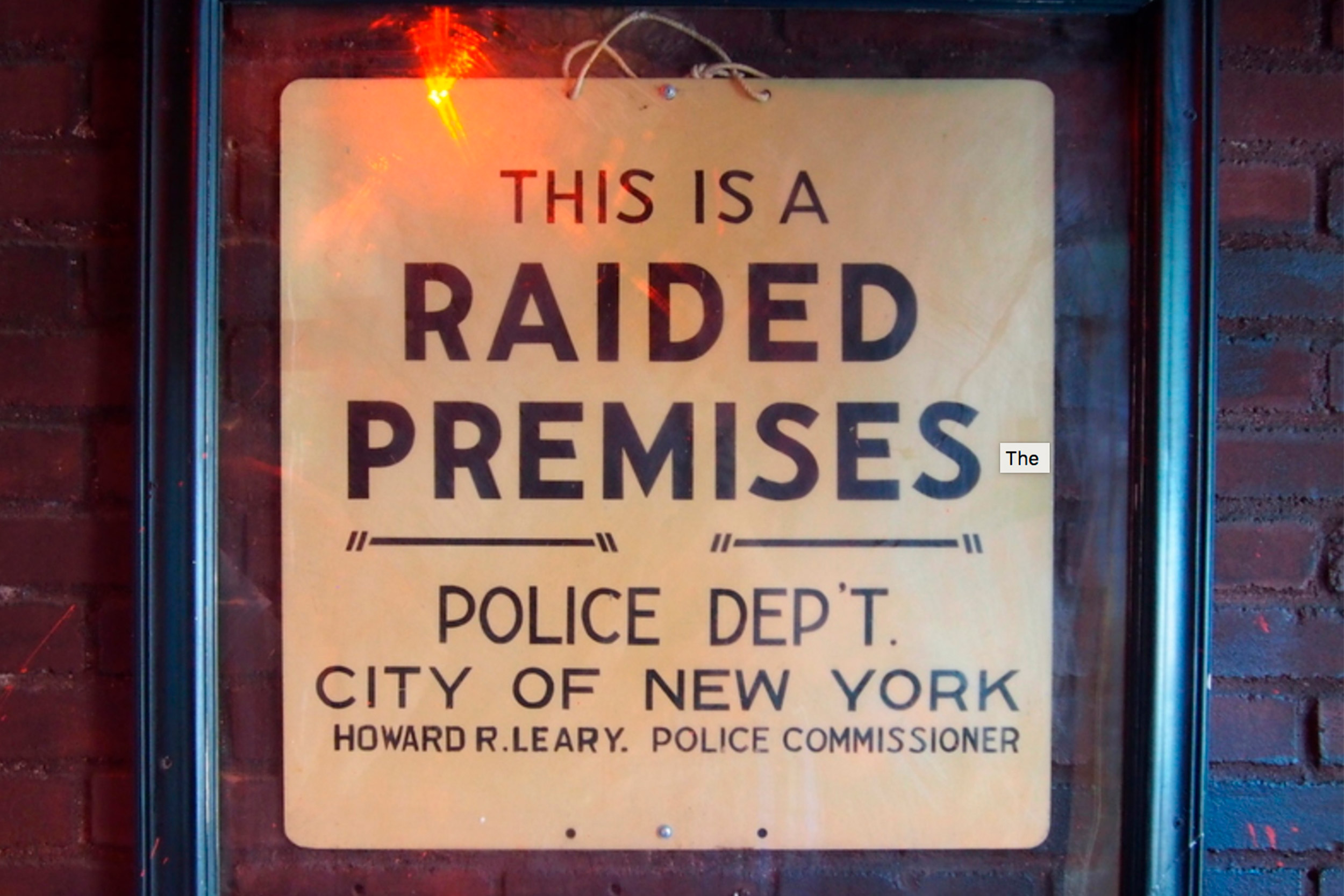

The “raided premises” sign just inside the door at the Stonewall Inn. Stonewall in 2011, during a pride march.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons; Rhododendrites/Creative Commons

McCarthy’s concern about the future echoes the struggles the Mattachine Society and the Gay Liberation Front grappled with years ago. He wonders how best to work within the system while still being considered radical.

“Much of what we have seen in policy in the modern era is an impulse to assimilation — we can get married, serve in military, be just like you. There’s been a real push to become part of these mainstream institutions, part of the system of laws and politics in the country. But the most important questions are these: Who does this leave out and what kinds of bargains have to be made to prove that we are just like straight people?”

With his students, he says he has “arrived at a fairly broad consensus that we need a both/and politics. We need a politics that is at once pragmatic and radical. We need different kinds of change agents, working in different locations with different tactics, to achieve these larger aspirations.”

Bronski is both hopeful and worried about the transgender rights movement that he likens to Stonewall in terms of the excitement and change it has helped inspire. “There is this enormous cultural change around the intersections of gender and sexuality and gender and identity and gender and, to a large degree, class and economics and money,” said Bronski. “But it’s also getting the most blowback from the Trump administration.”

Bronski said he could envision an effort by conservative groups to repeal the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision that ruled the Constitution protects same-sex marriage, but added that the potential outcome of such an attempt is less clear. “You do actually have hundreds of thousands of people probably who are now married. So if you repealed the law do you repeal their marriage? Do you grandfather them in? It gets complicated.”

Like Hammonds and McCarthy, Bronski, whose latest book is titled “A Queer History of the United States for Young People,” also sees hope in the nation’s youth.

“Today my gay students are incredible, and they have been for 10 years. They are more progressive and radical and on the edge than most people I know,” he said, “and that’s totally changed.”