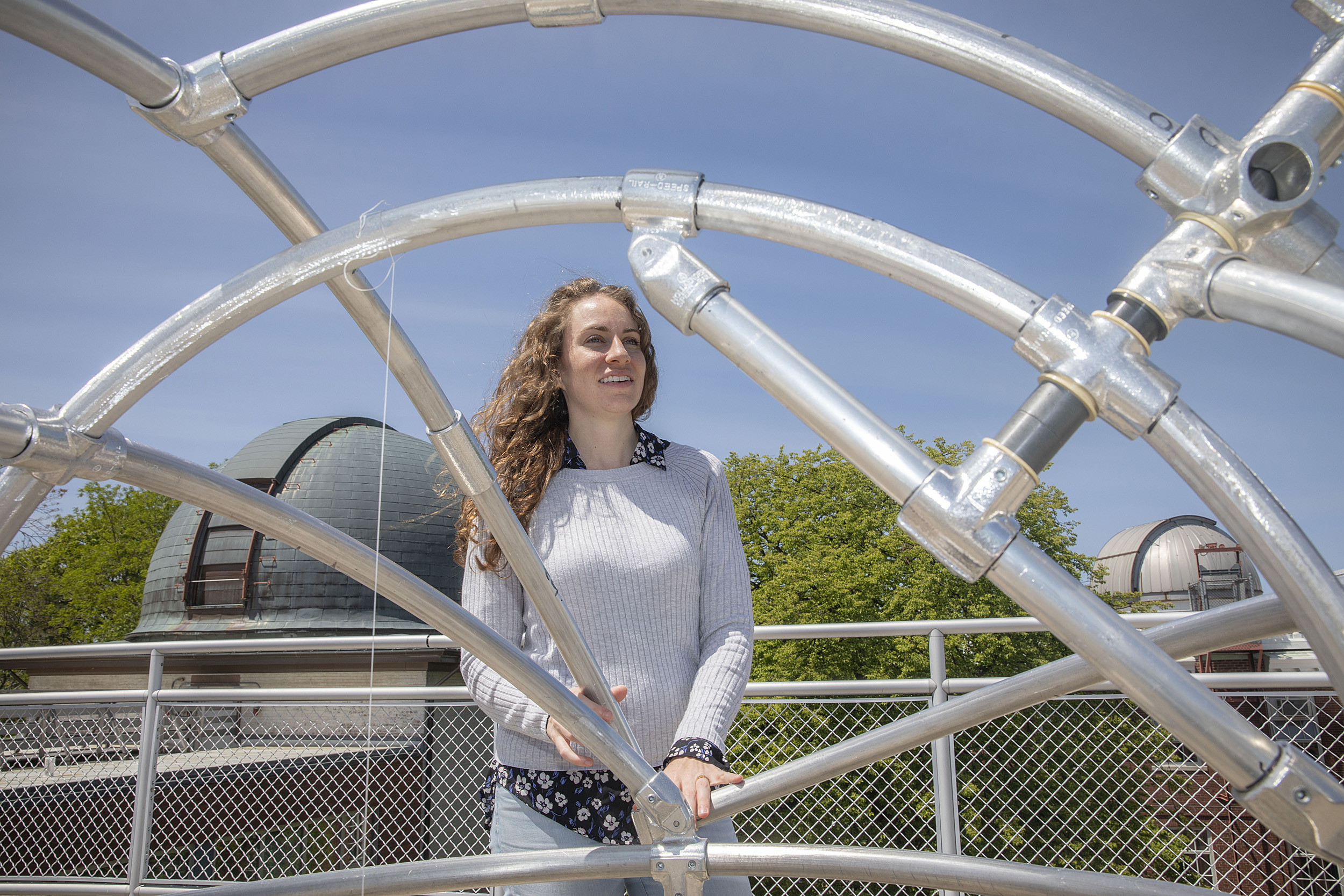

Laura Kreidberg studies the atmospheres of extrasolar planets to search for signs of life.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Are we alone in the universe?

Harvard astronomer Laura Kreidberg spends her days looking at extrasolar planets trying to answer the question

Laura Kreidberg’s work takes her out of this world to planets and solar systems light-years away, seeking the answer to the question posed by pretty much anyone who’s ever looked up at the stars: Is anyone else out there?

Kreidberg, a junior fellow with the Harvard Society of Fellows and an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, spends most of her time analyzing the atmospheres of distant planets to glean what information she can about their origin, nature, and current conditions — such as temperature and whether there is water present.

“A planet’s atmosphere is the key to understanding how it formed, how it evolved over billions of years, and ultimately what it’s like today,” Kreidberg said. “For example, if water is visible in the atmosphere of an Earth-like planet, that would tell us that the planet his maintained a substantial reservoir of water over geologic time and may be a prime candidate for the evolution of life.”

Her goal? To find biosignatures, telltale atmospheric signs of possible life on faraway extrasolar planets, or exoplanets.

“The smoking-gun evidence for life on Earth is that there is oxygen and methane [in the atmosphere] together at once, so the billion-dollar question for astronomers is, can we detect biosignatures like those molecules or something else in the molecules of an Earth-like exoplanet?” Kreidberg said.

On Earth, oxygen and methane are present together in surprising quantities, Kreidberg said, which hints at the presence of living organisms. “In ordinary circumstances, they would react to form carbon dioxide and water, so there has to be a constant source of production to increase their concentration in the atmosphere,” she said. “It’s very challenging to produce both quantities at Earth-like concentrations without the presence of life.”

Finding biosignatures is important but not definitive, since they would only show it’s possible there may be life, Kreidberg said. “We’re not going to see little green men waving at us,” she joked.

And while astronomers have yet to find evidence of extraterrestrial life, the sheer number of extrasolar planets offers hope that there is some out there.

“We know now that most of the stars in the galaxy have planets around them,” Kreidberg said. “These planets are much, much more diverse than the planets in this solar system. They come in different sizes; they come in different orbits … some of these are very hot, some of the planets are very different from the sun they orbit — they might be cooler or hotter; bigger or smaller.”

“These are the biggest questions: Are we alone and where did we come from? It’s such a privilege to be able to play some small part in answering those questions.”

Laura Kreidberg

The study of extrasolar planets is still a relatively new field. Their existence was only visually confirmed 24 years ago (though astronomers have hypothesized their existence since the 16th century). Today, more than 3,000 exoplanets have been discovered and close to 5,000 other bodies have been identified as candidates for life. They range from gas giants to ice worlds to Earth-like exoplanets that sit in their solar system’s habitable zone.

More like this

To study their atmospheres, Kreidberg uses a method called transmission spectroscopy. During observations, she measures the color of light that passes through a planet’s atmosphere when it passes in front of the star it orbits. That measured light is called the planet’s transmission spectrum. The color of light that gets absorbed by the atoms and molecules in the planet’s atmosphere tells her about its composition.

To observe the brightness of the stars, she uses NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope along with its Spitzer Space Telescope.

So far, she’s examined the atmospheres of large gas and ice giants, similar in size to Jupiter and Neptune. On these bodies, Kreidberg has made a number of discoveries, including water in the atmosphere of three planets and clouds that could be made out of exotic minerals like zinc sulfide or potassium chloride.

No matter what they are, the discoveries always fill Kreidberg with a sense of wonder. “There’s nothing like the moment of discovery when you are the first person to ever see it,” she said. “Every time we detect water it feels like a eureka moment.”

One moment in particular sticks out, Kreidberg said. It was back in 2013 when she was a Ph.D. student at the University of Chicago. While on an airplane, she looked at the data from a hot Jupiter-sized planet called WASP-43b, approximately 260 light-years away, and realized that she was the first person to discover water in its atmosphere.

“I freaked out,” Kreidberg said. “The person next to me thought I was crazy because I was so excited. There were these little bumps and wiggles on my laptop screen, and I was like ‘It’s water! It’s water! And they were like, ‘Can you please move away.’”

While some people’s eyes may glaze over the technical details of her work, Kreidberg comes upon plenty of evidence of the ongoing sense of wonder astronomy and the study of faraway worlds generates.

Earlier this year, in a paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, she potentially disproved what was thought to be the discovery of the first-ever exomoon about 8,000 light-years from Earth. Her piece sparked an uproar in a number of news and astronomy outlets, like The Atlantic, Forbes, and Space.com.

“These are the biggest questions: Are we alone and where did we come from?” she said. “It’s such a privilege to be able to play some small part in answering those questions. But every so often I get to go observe the night sky in one of the darkest places in the world, and you can see a jaw-dropping number of stars and know that almost every one has its own planets. It brings tears to my eyes every time — every time. You can never forget for too long the grandeur of the universe we live in.”