Researchers tracked Snowball’s moves as he boogied to songs by Cyndi Lauper and Queen.

Videos courtesy of Irena Schulz

So you think he can dance?

A study of YouTube star Snowball the cockatoo suggests humans may not be the only ones who can groove to a beat

New research starring YouTube sensation Snowball the dancing cockatoo spotlights the surprising variety and creativity of his moves and suggests that he, and some other vocal-learning animals, may be capable of some of the kind of sophisticated brain function thought to be exclusively human.

The white bird with the yellow-crested head became an Internet sensation in 2009 when videos of him grooving in perfect time to “Another One Bites the Dust” by the British rock band Queen went viral. To date, 7.3 million people have clicked on the three-and-a-half-minute clip and millions more have watched videos of the bird bouncing and bobbing to chart-toppers by Michael Jackson and the Back Street Boys.

But was he really dancing or just imitating his owner? Or did someone edit in music over his moves to make it look like he could dance? The questions troubled Ani Patel, a Tufts neuroscientist long interested in music cognition who had recently hypothesized that only vocal learners could move in time to a musical beat. He needed to know more.

“It was unbelievable when I first saw that video,” said Patel, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, who is working on a book about the evolution of music cognition based in part on his cross-species research. “I still remember it. I was staring at the screen and my jaw just hit the floor. I thought, ‘Is this real? Could this actually be happening?’ Within minutes I’d written Snowball’s owner.”

To test his theory, Patel and a team of researchers filmed Snowball while they alternately slowed down or sped up some of the bird’s favorite dance tracks. They watched as the parrot repeatedly synchronized his steps to the varied tempos.

“He predicted the timing of the beat, and he did this spontaneously without having been trained,” said Patel, whose 2009 findings were similar to those reported by Harvard researchers that same year involving the African grey parrot Alex and his ability to match his movements to the beats of novel songs.

Now, thanks to Patel’s new paper, “Spontaneity and diversity of movement to music are not uniquely human,” Snowball’s legion of fans have another video gem, a compilation piece featuring the parrot’s 14 different dance moves, some of which Patel and his collaborators suspect the bird came up with on his own.

The study published in Current Biology lists the more than a dozen separate movements Snowball liked to break out back in 2009 when dancing to Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” and the 1980 Queen hit. Researchers filmed Snowball dancing to the songs, then coded his individual movements. In order to qualify as a distinct move, the parrot had to repeat it at least two times at different points in the study. The report’s lead author, R. Joanne Jao Keehn, a cognitive neuroscientist and a trained dancer, analyzed the videos frame by frame and labeled Snowball’s different motions. She found that among the bird’s favorite steps are the “Vogue,” the movement of his head from one side of his lifted foot to another; the “Headbang with Lifted Foot,” when he lifts his foot and bangs his head simultaneously; and the “Head-Foot Sync,” during which he moves his head and foot in unison.

In addition to being wildly entertaining, the bird’s variety of movements point to a type of cerebral flexibility that suggests his creative choreography is not simply “a brainstem reflex to sound,” said Patel. “It’s actually a complex cognitive act that involves choosing among different types of possible movement options. It’s exactly how we think of human dancing.”

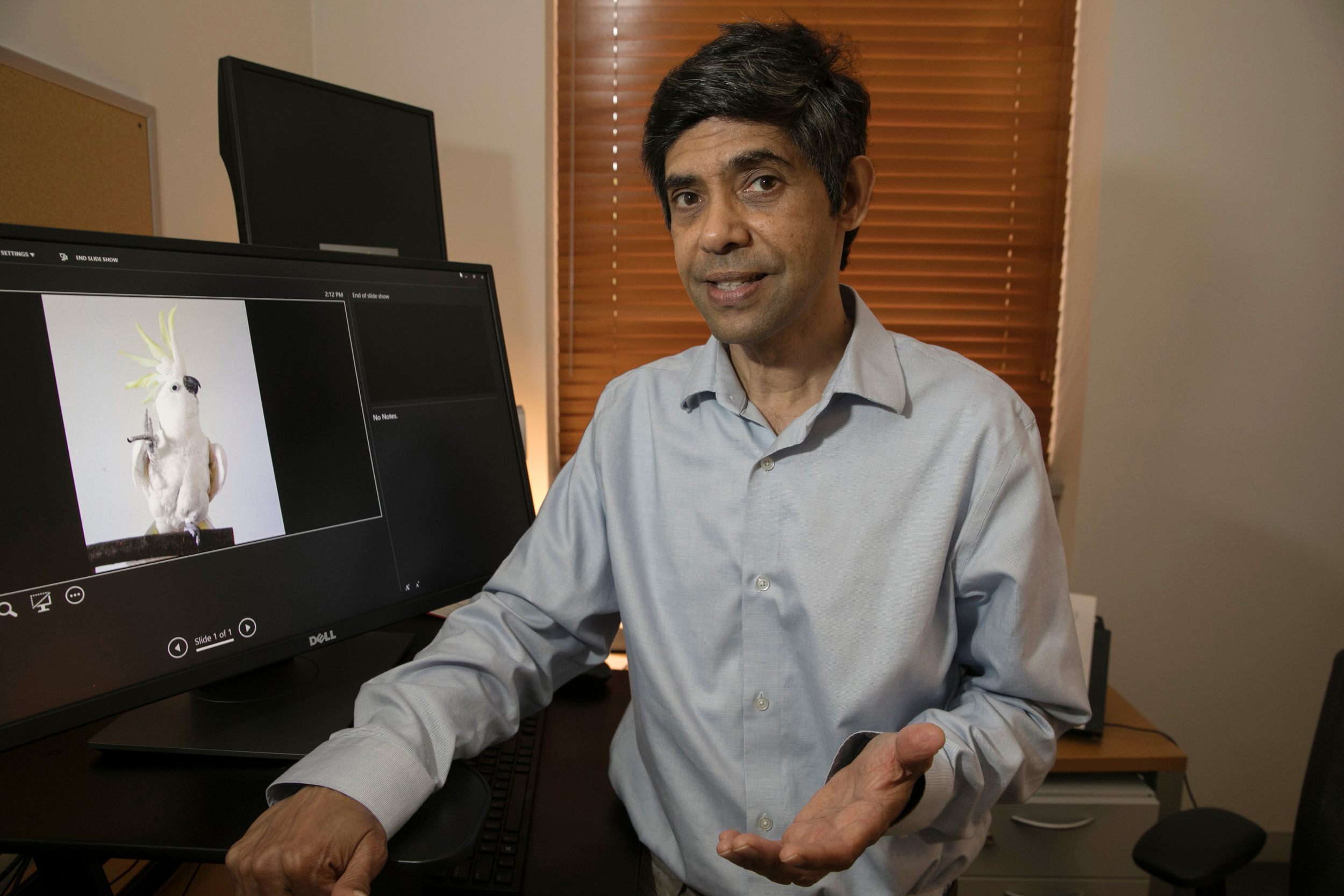

Tufts neuroscientist and Radcliffe fellow Ani Patel says he contacted Snowball’s owner within minutes of first seeing one of the videos of the bird dancing. “I still remember it. I was staring at the screen and my jaw just hit the floor.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

In the paper, Patel and his team list the five traits they believe are required for an animal to be able to spontaneously dance to music: vocal learning; the ability to imitate; a propensity to form long-term social bonds; the ability to learn a complex sequence of movement; and an attentiveness to communicative movements. Humans and parrots share all five.

“We think these five together in an animal brain lay the foundation for an impulse to dance to music with diverse movements,” said Patel, who noted other animals can do some of the five things but not others. Monkeys, for example, can imitate movements but have very limited vocal learning capacity, he said, and thus can’t move rhythmically to music. “It’s unusual for all five things to come together, and when they do it means a brain is primed to develop dancing behavior if it’s given exposure to music with rhythm and beat.”

Ever the skeptical scientist, Patel initially wondered whether Snowball might simply be copying the moves of his owner, Irena Schulz, who dances with him from time to time. But, Schulz, who has a master’s degree in biology and has been a willing research partner, said she only makes a limited number of motions while getting down with her fancy-footed bird. In addition, Snowball was never rewarded with food during the research, said Patel. Instead, he seemed to be dancing for social reasons, and for the pure fun it.

“Dancing has a deep social component,” said Patel, “and for him, dancing seems to be a social thing.”

Though the initial videos were made in 2009, Patel put the work aside to focus on a new job and a move across the country. But a few years ago, he was inspired to take another look when he read a scientific paper suggesting the term “imitation,” when used to describe something one species appears to mimic from another, implies a complicated biological process. Even if Snowball was emulating a human’s dance moves, Patel realized, he was translating those movements into a completely different motor system, solving what scientists call the “correspondence problem.”

“If he is actually coming up with some of this stuff by himself, it’s an incredible example of animal creativity because he’s not doing this to get food; he’s not doing this to get a mating opportunity, both of which are often motivations in examples of creative behavior in other species.”

Ani Patel

That itself “would be remarkable,” said Patel. Equally impressive, he added, is the possibility that the bird is creating the new moves on his own.

“If he is actually coming up with some of this stuff by himself, it’s an incredible example of animal creativity,” said Patel, “because he’s not doing this to get food; he’s not doing this to get a mating opportunity, both of which are often motivations in examples of creative behavior in other species.”

Patel thinks his cross-species work could help answer the longstanding question of whether musicality is an evolved part of human nature or purely a cultural invention that builds on brain circuits that have evolved for other reasons, a subject his new book will explore.

But the work could do more than just help solve a Darwinian debate. Patel suggests additional research with songbirds (which, like parrots and humans, are vocal learners with strong auditory-motor brain connections) could help shed light on why rhythmic therapies can improve brain function in patients with neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, stroke, dyslexia, and stuttering.

“There are connections between timing and rhythm and several other important brain functions we use on a day-to-day basis, like movement, speech, reading, and motor control,” Patel said. “So unraveling the mechanisms of rhythm processing in an animal model where we can measure things at the cellular and circuit level is a potentially powerful way to help advance rhythm-based interventions for neurological disorders.”

Happily for his fans around the world, Snowball, who is only 23 and could live for another 50 years or more, is going to keep on dancing.